To fight populism, we need to adopt a response not just for coping, but for overcoming and ultimately restoring decency and civilised discourse – laughter, the former president of Estonia, Toomas Hendrik Ilves, said in a speech at a conference dedicated to 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall.

As we survey open societies across the world since the heady days of 1989-91, we cannot help but observe – as Freedom House annually documents – not an increase but rather a steady decline in the number of democracies in the world. Once open societies across the democratic world – some so-called new, others old established ones – are one by one turning toward what they themselves proudly proclaim as “illiberal democracy”, characterised by restrictions of freedom, by corruption, arbitrariness and sometimes even by fear and repressions of the sort we in the formerly communist East strived so hard to leave behind us.

The various putative causes for this have been weighed and discussed enough. But to little avail: “Globalism”, “the revolt of ones left behind”, the “failure of the elites”, – I find many of these etiologies lacking, especially when those reasons are raised in discussions of what ails Eastern Europe. The framing of the argument ignores real data. It takes but a look at the Gini coefficient in these countries – the measure of income inequality – to see this is nonsense. Income inequality across the whole of the EU has been stable, and in some cases declining. Across the board it is much lower than it is in, say, the United States, where it has been high and rising, especially under the current populist administration. And there is no absence of populists in the countries with one of the lowest income differential coefficients, Hungary.

What we do see across countries regardless of the actual inequality is the exploitation of emotions against the “other” – be they foreigners and immigrants, or the domestic other, what populists call “the elite”. Be it the United States, the UK or Hungary, where populists are in power, or among significant opposition parties such as Italy’s Lega, Germany’s AfD, the Swedish Democrats and France’s National Front (now renamed Rassemblement National), paranoid opposition to an enemy has become a major trend among democracies.

In some cases, such as Hungary or here in Estonia, two of the most racially homogeneous countries in Europe, the foreign “others” are imagined; politicians rage against them, yet they are not present in any noticeable number. However, as a result, the few foreigners who are in these countries are subject to harassment, sanctioned by hateful rhetoric.

The “elite” and ressentiment

More interesting to me, since it is present in all populist countries, is hatred of the so-called elite, one’s own compatriots, people who share the culture and look like us.

There are two components to this – one proposed, the other described – by German thinkers.

The first comes from Carl Schmitt, a legal scholar and generally considered the smartest Nazi, who proposed an alternative definition of politics to liberal democracies. Whereas politics in democracies is thought to strive for compromise and common solutions, Schmitt, in his The Concept of the Political, argued that the goal of politics is the destruction of the other, where political opponents are the enemy to be liquidated. One of the politicians in power today in Estonia has called for precisely this: the annihilation of the largest political party, currently in opposition due to the current prime minister ignoring the norms of democratic electoral procedure.

The other concept we see working overtime in the current populist revolt is a moral calculus described first by Friedrich Nietzsche, what he disapprovingly called a slave morality above all based on resentment. In his Genealogy of Morals, he calls this emotion ressentiment, using a French word, claiming that the notion was absent in the German language. Ressentiment is a hateful desire for revenge, which Nietzsche says is the basis of the “slave revolt” that in his estimation forms the basis of Christianity. Leaving Christianity aside for the purposes of our current discussion, Nietzsche says that the slave, a member of a repressed underclass, defines himself as “good” and the elite as “evil”. (By contrast, the elite – in Nietzsche’s terms, the aristocracy – also defines its own actions as “good” but the actions of others simply as “not good,” or “bad”, without any moral implications.)

In the populisms of today’s liberal democratic order we see these two operate in tandem. Populists appealing to ressentiment proclaim to speak for the common man against an imagined elite that must be destroyed.

Some elites can reasonably elicit ressentiment. The clannish aristocracies that dominated Europe for centuries are one such elite. Another is the product of ethnic or racial hierarchies, such as the ones enshrined in law in Jim Crow America. But a second kind of unmeritocratic elite also exists. It is the result of collaborationism-based stratification, where a party-based nomenklatura enjoys extra privileges from joining an authoritarian, undemocratic regime. The more loyal you appear to the CPSU, the NSDAP, Fidesz or the coterie in Donald Trump’s MAGA camarilla, the greater the odds to get ahead, to get that government, contract, that ambassadorial or ministerial appointment.

Meritocracy has its flaws – big ones. All too often the beneficiaries of meritocracy lack a sense of the noblesse oblige that kept social peace in times of aristocracy – a sense of obligation to help others that once was also present in the United States when robber barons such as Andrew Carnegie spent lavishly on the public good. Nonetheless, we can agree that generally, meritocracy has led to better outcomes than hereditary aristocracy or corrupt collaborationism. Better outcomes, because in meritocracies stupidity or incompetence is neither rewarded nor given a pass, as it was in aristocracies and routinely is in party-loyalty based arrangements of authoritarian states. In a meritocracy, the ones at the top are constantly plagued by the rival competence of others. In meritocracies, competition is eternal and essential.

It is this feature of illiberalism – the hatred of the elite – that gives me the greatest hope for its temporariness.

Populists simplify and reduce the complexity of societies to simple problems supposedly created by elites, and assume that these societies are so secure that no disaster can actually befall them no matter who is in charge. We can see the results of what can happen when incompetent populists and their cronies take over by studying the fallout of the Trump administration’s approach to Ukraine. The same is true of any issue were competence and experience previously was a sine qua non. Anyone who has really dealt with avoiding disaster – be it military planning, cyber-attacks, or financial disaster – knows what a difficult and constant state this is.

Yet the populists do not understand this. Indeed, the attitude of populists is that elites have no qualifications and thus there are no consequences from replacing them with a crony. The failure of the incompetent politics of ressentiment is its most outstanding and common feature.

A strategy, not just for coping

All of this is so well studied and documented that in social psychology, it even has a name: the Dunning-Kruger Effect – the tendency of meagre intellects to overestimate their knowledge and intelligence. This phenomenon was first discussed in a paper in 2011 by David Dunning and Justin Kruger. The study focused on subjects’ ability to gauge their own performance relative to others, an ability Dunning and Kruger termed metacognition. The incompetent, they went on to argue, suffer a double curse: people whose performance is subpar are not only less skilled, but they are unaware they are less skilled. They are simply unaware of their incompetence, in both the task at hand as well as their competence relative to others.

I would go so far as to say that the Dunning-Kruger Effect is the core functioning metaphor for the populism we are inundated with today. People who fail to recognise their incompetence make incompetent decisions on issues that require a highly developed set of skills. And when they fail, they place the blame on others. This is a dangerous, and potentially self-perpetuating mechanism. Unchallenged, the failure can constantly be foisted on the menacing “other”, foreign or domestic, lurking in the shadows, thwarting the populist at every turn.

Which is why we need to adopt at least a strategy, a response not just for coping, but for overcoming and ultimately restoring decency and civilised discourse: Laughter.

All this incompetence is all so laughable. Yet, we don’t laugh. Instead we are appalled, as we believe in decency and the progress made by the accumulation of knowledge and our hard-learned respect for humanity. We share outrageous tweets, we despair, we shake our heads and hope it will soon be over. What we fail recognise is that it is all laughable. It is ridiculous – they are ludicrous. Alas, we cling to the idea that mockery is outside the realm of the acceptable. We – but not they! – find it uncivilised to laugh and mock. It’s just not done in our societies. For we do not want to become like them. Yet I fear we are well past Marcus Aurelius’ dictum, that the best revenge is not to become like them.

What the pompous and preposterously self-important, stentorian little minds in power cannot stand – what exposes their weakness, their nakedness – is ridicule. We know this from Hans Christian Anderson’s story The Emperor’s New Clothes, a tale of the ridiculousness of a stupid ruler, kept in power only by the willingness of his subjects to go along with what everyone realises is utter nonsense.

There is no need to go along with it. None. In real life and not from a fairy tale, we have the perfect example of the power of ridicule in the downfall of Nicolae Ceaucescu, the Romanian communist despot with one of the most effective repressive apparatuses in the 20th century.

What happened when Ceaucescu, faced with increased unrest in 1989 following the liberation of Germany, Czechoslovakia and other authoritarian European countries, faced a crowd before him and began one of his risible speeches promising assembled Romanian miners a pitiful raise? Someone in the crowd laughed at his promises. Soon others joined in. The crowd laughed at the dictator and kept on laughing. It was new. He did not know how to respond. He grew distraught, and continuing with his communist jargon, appealed to the crowd, “Comrades, comrades, calm down!” But the miners were not his comrades and he was simply a privileged fool with the trappings of power and a title. Ultimately he fled, whisked out of Bucharest in a helicopter. Now, while our current populist leaders in Europe hardly deserve Ceaucescu’s ultimate fate, I do believe public laughter and ridicule is our best response, our antidote to the preposterous antics on display every day.

If you have doubts, I would direct you to a video of the green-shirt guy, a clip showing a man unable to contain his laughter when two people wearing their MAGA hats disrupted a meeting in Arizona to discuss immigration. “The green shirt guy” is now a meme. Why did the video go viral? Because, as with the case of the unclothed emperor and Nicolae Ceaucescu, it was laughter that broke the spell. The spell of horror, of “My God, what did they say now?”, of the sheer din by which our populists dominate our public square these days. It is important to note that the laughter of the Green Shirt Man is not even heard above the brutish yelling of the MAGA hat wearer. But it is the populist foot soldier whom no one remembers. The content of her disruptive yelling is quickly forgotten. Meanwhile the Green Shirt Man speaks – or laughs – for the rest of us.

So I say laugh. Laugh at their press conferences, laugh at their statements. Laugh publicly. Laugh when you see them. We all know how silly their statements are, how laughable their pronouncements can be.

A dishonor to our heritage

The dream, ever since the stirring of national consciousness here in Estonia some 200 hundred years ago, when we here on this small patch of land began to understand that we too were humans and no less capable than our overlords, that the natural order of things did not mean we were a natural underclass, that our language too was a real language – that dream has been equality and freedom.

It is the struggle to achieve liberty and equality that is the dominant motif of our history for the past two centuries. From the Alexander School, asking that we be educated in our own language, to the freedom marches in 1917 in Petersburg. From the War of Independence and the establishment of statehood. Through the darkness of one occupation after another and yet another. Through mass deportations, mass flight to the West, through the summary executions, through the false hope of the 1960s Soviet “thaw”. Through the reawakening in the 1980s, the singing, the hard first years when we learned the lessons of real independence, through the struggles to rejoin Europe, the West, the European Union and NATO, it was freedom we wanted, liberté and equality, égalité – to be taken as free and equal by those who had fared better than we, but otherwise were not better than us.

We need to be reminded, especially today, when so many have forgotten where we were and how far we have come, of how sacred freedom and democracy are. We especially need to be reminded by those who know from living memory what its absence means. We need to collectively recall, to remember. Especially these days, when we see among us, and at the highest levels of power, a forgetting, an amnesia, of what our nation has aspired to for two centuries.

We want our speech to be free: after all, we have known it for too few periods in our history. We want to be able to love whom we love, we want to believe what, and in what, our consciences have brought us to. We must reject the incompetents that have ridden to power through hatred and ressentiment, and who sincerely believe, as Carl Schmitt advocated, that the goal of politics is to destroy the opposition.

The imprint of our achievements in history, fleeting though it may seem in time, is too strong to erase with the boorish belching and insults that today passes for political speech in too many Western countries. We have worked too hard, we have sacrificed for too many years, sweated too long, for too many generations to allow this to happen to the efforts of all those who preceded us. The dream of our forefathers, in the fields of the baronial manors, in the Gulag, on the Song Festival grounds – their dreams are our dreams, and we won’t let them be trampled upon.

We must never stop laughing at those who dishonour our heritage.

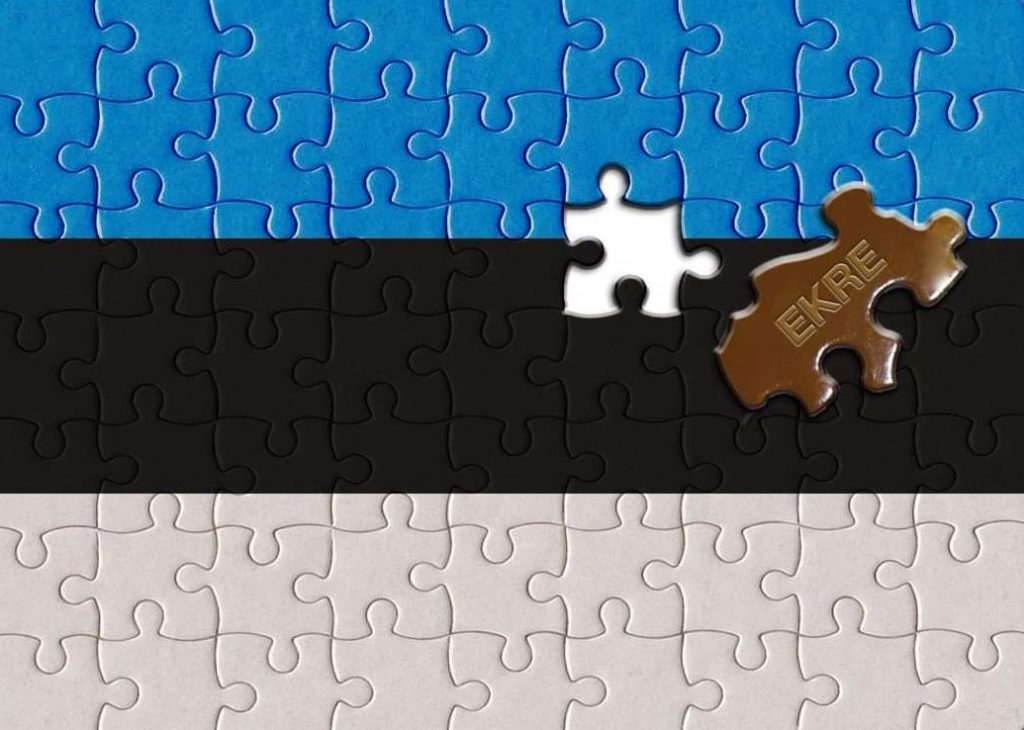

The above essay was first published in The American Interest. Republished by kind permission. The opinions in this article are those of the author. Cover: A puzzle of Estonian national flag, with a piece bearing the name EKRE (standing for the populist Estonian Conservative People’s Party) that does not fit in (courtesy of Facebook page EKRE Tõbraste Klubi).