Edgar Savisaar, one of the leaders of the Estonian independence movement in the late 1980s as well as the head of the government when Estonia regained its independence from the Soviet Union in August 1991, died on 29 December at 72.

Savisaar, the founder of the Estonian Popular Front in the late 1980s and the Centre Party in the early 1990s, dominated Estonian politics for almost 30 years – from 1988 until 2015, when an ill health and corruption allegations against him ended his political career. He was the last head of the Estonian government under the Soviet rule – the chairman of the Council of Ministers – as well as the first acting prime minister after Estonia regained its independence from the Soviet Union on 20 August 1991.

Born in prison

Edgar Savisaar was born in the Harku prison on 31 May 1950 – his parents, farmers Elmar and Marie, had been convicted in 1949 for resisting the Soviet-imposed collectivisation. Elmar was sentenced for 15 years (freed in 1952) and Marie for five years (freed in 1950) in prison.

After graduating from high school, Savisaar continued his studies at the University of Tartu, where he graduated in 1973 with a degree in history. In 1980, he wrote his candidate thesis in philosophy on the topic “Social Philosophical Foundations of the Global Models of the Club of Rome”.

For most of the 1980s, Savisaar worked as a little-known apparatchik in the Soviet Estonian governmental institutions – including as the head of department of the communist-ruled National Planning Committee from 1985-1988. At the same time, he also worked as a lecturer at the philosophy department of the Estonian Academy of Sciences.

Proposing the idea of self-managing Estonia

He first broke into the Estonian public consciousness in the autumn of 1987, when he co-proposed (together with Siim Kallas, Tiit Made and Mikk Titma) the idea of self-managing Estonia (the Estonian acronym IME; the acronym also means “a miracle”) that was enthusiastically discussed in the Estonian society. The idea was to make Estonia economically independent from Moscow – adopt a market economy and establish the country’s own currency and tax system.

Although formally it was no more than a suggestion to grant Estonia greater decision-making power to better manage the economy, many people nevertheless hoped the country would gradually manage to separate itself from the Soviet Union, or at least achieve greater autonomy. The proposal failed to get a positive reply from Moscow, although the Soviet Union now allowed private enterprise.

His big break came in the spring of 1988, when during a current affairs programme, broadcast live on 13 April on the Estonian state-run television, he came up with an idea to establish a “popular front” – a movement that would politically engage ordinary Estonians, not members of the Communist Party.

The Estonian Popular Front

The Popular Front of Estonia, as it was to be officially called, became the first political mass organisation in the Soviet Union outside of the Communist Party since 1920. Initially formed to support perestroika (a political movement instituted by Mikhail Gorbachev for reform within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union), the Popular Front eventually developed ideas of the Estonian national independence and created the Singing Revolution phenomenon – a series of mass concerts in Tallinn in June and September 1988, where people sang patriotic Estonian songs and for the first time in almost 50 years, waved the national tricolour again.

Intellectually brilliant, charismatic, hard-working and good organiser, Savisaar thrived in the period of change – and quickly rose to become one of a new generation of Estonian political heavyweights. The Popular Front was also one of the main organisers of the Baltic Chain on 23 August 1989, when approximately two million people from Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania joined hands, forming a human chain from Tallinn through Riga to Vilnius, spanning 675 kilometres, or 420 miles. It was a peaceful protest against the illegal Soviet occupation and also one of the earliest and longest unbroken human chains in history.

By 1990, the Communist Party was gradually falling apart and losing its monopoly on power – and the Savisaar-led Popular Front became the strongest political organisation in Estonia. As a result of the first multi-party candidate general election in Estonia since the Soviet occupation, in March 1990, the Popular Front won the largest number of representatives in the Supreme Soviet of Soviet Estonia (legislative assembly in the Soviet-ruled Estonia) and Edgar Savisaar was appointed the chairman of the Council of Ministers (effectively the government).

The head of the government

By that time, the Popular Front had already abandoned the idea of a union agreement with the Soviet Union and supported full independence for Estonia. On 8 May 1990, the country’s name, the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic, was abolished and replaced by the Republic of Estonia. On 1 November, Estonia’s own border guard was re-established. A referendum on the country’s independence was organised on 3 March 1991: 77.8% of the participants voted in favour of the Estonian independence – but for Moscow, it meant nothing.

Those who worked with Savisaar, recall that he was an extremely hard worker at the time. “He was a hard worker and no mistake during those days. Even when we sometimes worked long evenings in the Supreme Council, the light was still on in his office when we left for the night. He downright exhausted many others that worked on grand designs with him,” Heinz Valk, an artist who was also one of the Estonian independence movement’s leading figures in the late 1980s and early 90s, told Estonian Public Broadcasting after Savisaar’s passing.

“But it was an era when no one had time to consider their health or other aspects of personal well-being. Everything had to be full steam. And Edgar was. I would not hesitate to put him on top if I had to choose the most valuable players from the period,” Valk said, adding that Savisaar had the ideas and political instinct required to pull off necessary manoeuvres and the restoration of Estonia’s independence would not have gone as smoothly without him.

Defending Toompea

It didn’t always go smoothly. A movement initiated by the Russian-speaking workers of the Tallinn-based Soviet state factories organised on 15 May 1990 a mass demonstration in front of the Estonian government and parliament building in Toompea, which escalated into a violent attack on Toompea Castle. In what became one of Savisaar’s greatest hours, he addressed Estonians via public radio broadcast. “Toompea is under attack! I repeat, Toompea is under attack!” he said.

Thousands of pro-independence Estonians immediately rushed to the defence of Toompea and, together with the few policemen, prevented the occupation of the castle. It was also remarkable that the whole confrontation ended without bloodshed – the Russian demonstrators were let to walk away peacefully.

But a worse threat to the Estonian quest for independence was to come. On 19 August 1991, eight Soviet hardliners, including the head of the KGB, made an attempt to take control of the country from Mikhail Gorbachev, who was on holiday in his dacha in Crimea. The putschists in Moscow also sent more Soviet troops and armoured vehicles to Estonia.

On that day, Savisaar was on a working visit to Stockholm. While there was no direct flight back to Tallinn on the day, he flew first to Helsinki, Finland – where he met up with Lennart Meri, Estonia’s foreign minister at the time. In Helsinki, Savisaar’s team hired a small motorboat that ferried him over to Tallinn by late that evening – and he immediately rushed to Toompea to make sure things were under control.

Restoring independence

Versions somewhat differ on what exactly happened next. Both the government and majority of the parliamentarians realised that what had just happened in Moscow was a “now or never moment” for the country – however risky, they decided to act swiftly and proclaim independence from the Soviet Union.

But there was also an issue of dispute, the choice between two options: whether to declare a new independent Republic of Estonia or, based on legal continuity, restore the previous Republic of Estonia that was declared in 1918 and occupied by the Soviet Union in 1940. Some of Savisaar’s fellow politicians in the Popular Front would later claim that he wanted to go for the first option and preserve a close relationship with Russia – a claim rubbished in a 2021 radio interview by Raivo Vare, a minister of state in his government.

But, advocated by Marju Lauristin, a deputy leader of the Supreme Soviet and until that moment a staunch ally of Savisaar, the second option was chosen (Lauristin would later say that Savisaar never forgave her this “betrayal”). At 11:02 PM on 20 August, the Supreme Soviet of the Republic of Estonia approved the declaration of Estonian National Independence, coordinated with the Estonian Citizens’ Committees – after lengthy discussions, the version of legal continuity was chosen. Estonia had restored its independence.

The acting prime minister

Savisaar carried on as the head of the government – as the acting prime minister (Mart Laar would become the first head of the government to be named prime minister in 1992, after the ratification of the new constitution and first free election).

But the times were tough. The economic chaos that followed the disintegration of the Soviet Union hit Estonia hard; the Estonian economy was still geared towards the East and the Russian ruble was still the currency. Estonia suffered from hyperinflation and ever-increasing deficit of goods. Even ration stamps were introduced. During the winter, preparations were made to evacuate parts of Tallinn due to shortage of fuel.

In January 1992, butter disappeared from the shops. Savisaar was shown on the national television’s evening news programme personally invading a butter warehouse – not wanting to send an ounce of food to the inflation-ravaged trade, producers kept it in their warehouses, hoping for a continued rise in prices, with the Estonian national currency, the kroon, looming in the horizon.

On 29 January 1992, Savisaar managed to win a vote of non-confidence in the parliament but stepped down when it turned out impossible to introduce a state of emergency. He was replaced by a technocratic government under Tiit Vähi, until that point a transport minister in his government.

Building the Centre Party

In October 1991, Savisaar had founded the Centre Party from the ashes of the Popular Front – and after stepping down as the head of the government, he directed his energy to building up the party. The Centre Party became third in the 1992 general election, gaining 15 seats in the 101-strong parliament – a result below Savisaar’s expectations – and was left in the opposition.

From 1992 until 1995, Savisaar was the vice-speaker of the parliament (a position traditionally reserved for the leader of the opposition). Following the 1995 general election, the Centre Party was invited to form the coalition government with the Tiit Vähi-led Coalition Party and Country Union that had won the election with 41 seats.

Savisaar became the interior minister in Vähi’s government. But just seven months later, in November 1995, when Savisaar was accused of recording private conversations of other politicians, the entire government faltered. Savisaar resigned and announced his intention to leave politics altogether. And for a while, he did – residing quietly in his Hundisilma farm in Lääne-Viru County.

However, in the following year, he made a grand return as the Centre Party’s leader, which evoked the first of many splits to come in the party – each time, some leading members, disillusioned with Savisaar’s leadership style, either left to establish a new party or join another existing one.

Attracting Russian votes

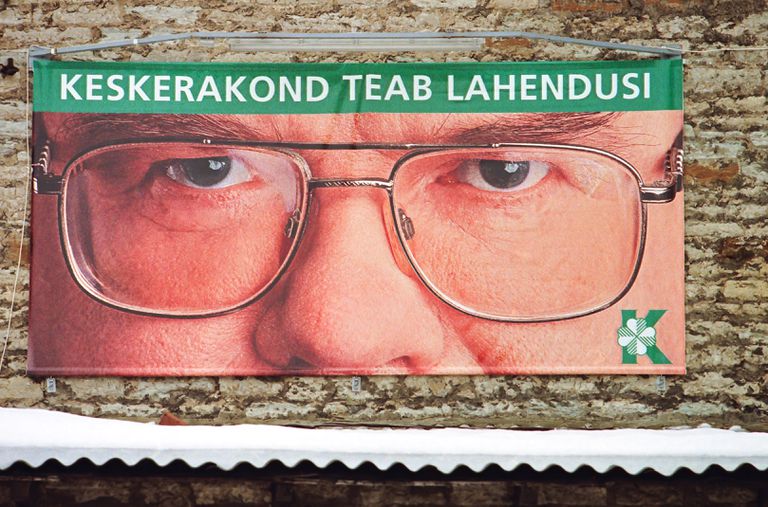

In 1996, he participated in the local elections and became the chairman of the Tallinn City Council – the start of his long career in charge of Tallinn. With the elections in Tallinn, he also discovered that his party could gain more votes and seats by appealing to the Estonia’s Russian-speaking community – and gradually, the Centre Party became by far the most popular party among the local Russians (the position it holds to date).

In the 1999 general election, the Centre Party actually won the election for the first time – but it was left out in the cold by the Pro Patria Union, the Reform Party and the Social Democrats that formed the new government. The same happened in the following general election, in 2003 – again, the Centre Party won, but the new party, Res Publica, formed the government with the Reform Party and the People’s Union of Estonia.

The reasons why the Estonian political landscape became polarised along the lines of the Centre Party versus the rest (much like today the Estonian Conservative People’s party versus the rest), were both policy-based as well as revolving around Savisaar’s personality. Some were in awe of him, the others mistrusted or feared this political heavyweight.

The economically liberally minded Pro Patria Union, the Reform Party and Res Publica were also against Savisaar’s proposal to introduce progressive income tax in Estonia (Mart Laar’s government had in 1994 introduced a flat tax system). And while Estonia was preparing to join the European Union (which it did, in 2004), Savisaar’s stance about Estonia’s EU membership was vague at best and negative at worst.

Principality of its own in Tallinn

Savisaar became the mayor of Tallinn in 2001, a post he held until 2004. In April 2005, he returned to the government as the economic affairs and communications minister in the Andrus Ansip-led coalition government of the Reform Party and the Centre Party. Ansip was relatively inexperienced in the government – he had been a mayor of Tartu – and a joke that “Andrus Ansip is the prime minister in Edgar Savisaar’s government” circulated around. Savisaar worked in the job without a major scandal until the next general election in March 2007 – and it turned out to be his last ministerial appointment.

After Ansip decided to ditch the Centre Party, following the general election, Savisaar returned to the Tallinn city government as a mayor. His party had won an absolute majority in the municipality in every local election since 2002 (and would continue to do so until 2021) – largely due to the overwhelming popularity of the Centre Party among Russian-speaking voters – and assuming the mayoral position was a formality for Savisaar.

Although the mayoral role was first considered somewhat lightweight for Savisaar, he managed to create a sort of principality of its own in Tallinn. The Savisaar-led city government introduced free public transport and created municipal housing. It even established its own television channel, let alone multiple papers – all of which worked to reinforce Savisaar’s personal brand, while his party was increasingly compared to a sect.

A cult following

When the new Andrus Ansip-led Estonian coalition government moved a Soviet war memorial called the Bronze Soldier from the Tallinn city centre in April 2007 and it caused a widespread street riot by approximately 3,000 Russian-speaking city residents, Savisaar spoke out against the removal of the monument and accused Ansip of deliberate attempts of splitting the Estonian society by provoking the Russian minority. In response, many government officials and public figures stated distrust and disrespect towards Savisaar.

Increasingly, suspicions that he was too cosy with the Russian Federation’s officials became widespread. In 2010, Savisaar was alleged to have received money from Vladimir Yakunin, then the head of the Russian Railways. Jakunin allegedly said that 1.5 million euros would be given to the Centre Party to support the party’s campaign ahead of the Estonian 2011 general election. All other Estonian parties ruled out forming a government coalition with the Savisaar-led Centre Party, effectively meaning it was destined for opposition for years to come.

In 2011, Savisaar was challenged in the Centre Party’s leadership for the first time – by Jüri Ratas (who would eventually beat him in 2016), but to no avail. Increasingly, he faced internal opposition in the party and many of his former staunch supporters went public to say that Savisaar had lost his peak powers and he should hand over the baton to the younger generation. All this criticism didn’t disturb his cult following, however. In the 2013 Tallinn city council election, he gathered almost 40,000 votes and in the 2015 general election, over 25,000 votes – both records in Estonia until this day.

Declining health

But shortly after the 2015 election, a personal tragedy struck. In March 2015, Savisaar fell critically ill and was taken to Tartu University Clinic. He was suffering from the Streptococcus bacteria, which caused a toxic syndrome – and due to an acute infection, doctors had to amputate one of his legs above the knee.

He survived and after months in the hospital, even returned to work as the mayor of Tallinn – but was then hit by an allegation that brought him down. In July 2015, the Estonian Internal Security Service launched a criminal investigation on Savisaar and six others in relation to bribery allegations. He was suspected of accepting bribes worth hundreds of thousands of euros in 2014 and 2015 on behalf of himself and the Centre Party.

Because of the ongoing investigation, Savisaar was suspended from the mayor’s office in September 2015. He clung to the party leader’s position, but now surrounded by second and third-rate political wannabes, became an increasingly isolated figure. In 2016, Jüri Ratas challenged him again for the Centre Party’s leadership – and this time, won. Savisaar’s long and extraordinary political career was over.

Ratas offered Savisaar to become the “honourable chairman” of the Cente Party – but the man who had founded the party in 1991, bitterly refused.

In the 2017 local election in Tallinn, Savisaar attempted a comeback, forming an electoral alliance with a bunch of disgruntled former Centre Party members and few entrepreneurs – but the list bombed, failing to receive enough votes to get over the five per cent threshold needed to be elected. However, Savisaar personally still received over 3,000 votes, which earned him a personal mandate in the city council. In the 2021 local election, he joined an electoral alliance called Vaba Eesti (Free Estonia), which had been accused of being anti-vaccination. But this time, he received a mere 437 votes – a far cry from his record of 40,000 – and was not elected. It was a somewhat sad career ending for the politician who had once so dominantly captivated Estonia.

Bribery allegations against him eventually came to nothing – in 2018, Savisaar was freed from political corruption trial as court determined him seriously ill and thus unable to stand trial or carry a punishment if convicted.

His health never recovered and in the last few years of his life, Savisaar was mainly drawn from the public life. However, he did attend the meetings of the former prime ministers that take place annually on 20 August, celebrating the day Estonia’s independence was restored.

Edgar Savisaar died in East-Tallinn Central Hospital on the afternoon of 29 December.

A definitive place in Estonian history

Following the announcement of his death, the Estonian president, Alar Karis, said that without Savisaar, Estonian politics would have been duller.

“Three decades of Estonian politics would have been duller without Edgar Savisaar, and less colourful. We will remember the important role he played in the restoration of Estonia’s independence, when he first led the Popular Front and then the government, and later in shaping the Estonian party landscape, as the chairman of the Centre Party,” Karis said. “The vigour of his thoughts and actions, also the occasional contradictoriness, deservedly earned him the nickname Rhinoceros.”

The country’s prime minister, Kaja Kallas, said that although she never came into contact with Savisaar in politics, they are united by the fact that they both know the worries and pains of being prime minister.

“From my childhood, I have several major memories of Edgar Savisaar. I remember that as a child, I danced in the folk-dance collective ‘Sõleke,’ which had been asked to perform at events of his election campaign. And from later, I remember how Edgar Savisaar, together with my father and many others, worked courageously for the restoration of Estonia’s independence,” Kaja Kallas, leader of the Reform Party, said. Her father is Siim Kallas, a former prime minister of Estonia, who over the years was both an ally and a rival of Savisaar.

“Yes, Edgar Savisaar was controversial, but he was nevertheless a politician with a brilliant mind, a great personality and he has a definitive place in Estonian history. We are grateful for everything he did for the restoration of Estonia’s independence. Thank you, Edgar, and a good journey to you,” Kallas said, offering her condolences to Savisaar’s loved ones.

Marju Lauristin, who worked closely with Savisaar in the Popular Front from 1988 until 1991, compared him to Konstantin Päts, an Estonian statesman and the country’s president from 1938–1940.

“I believe that Savisaar’s role in the restoration of Estonia’s independence is comparable to Päts’s role in Estonia’s independence after the First World War. Of course, as a personality, as a politician, he was just as controversial or even more controversial than Päts. Päts was also a great role model for Savisaar. It was no coincidence that we called him ‘Savipäts’ among ourselves,” Lauristin told Estonia’s Vikerradio in an interview after the politician’s passing.

“By nature, he was a military leader; although he never led a military operation, he had the attitude of a military leader, he had a very strategic vision and he had a special talent for staging history, for setting in motion such great mass scenes, such mass movements,” she said, adding that without Savisaar the Baltic Chain would have not happened.

Another important thing to be grateful to Savisaar for, according to Lauristin, was his work to repeal the Molotov-Ribbentrop secret protocols that in 1939 had divided the Baltic states and Poland between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany. Lauristin recalled attending the last Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union (the legislative body of the USSR) in Moscow with Savisaar and other Baltic MPs, where one of the objectives was the recognition and repeal of the secret protocols.

“Again, it was Savisaar, together with another brilliant [Estonian] politician and scientist, Endel Lippmaa, who both conceived and carried out this action from the very beginning. This is something else that has perhaps not been talked about, but for which we must also thank Savisaar,” she noted.

However, Lauristin conceded that Savisaar’s very forceful traits were later an obstacle for becoming the leader of a democratic Estonia, even though he would have wanted and deserved it. “He did not have the desire or the will to participate in what for him was a boring and petty democratic process that took into account many others. He was authoritarian in character, not in outlook, and this played a very unfortunate role in his fate,” Lauristin described.

“But looking back in history, it is not the character of a person that is judged, but what they have given and achieved. What Savisaar has given to Estonia, to the Estonian people, I think that will go down in history,” she concluded.

Edgar Savisaar married three times and was the father of four children. From his marriage to Kaire Savisaar, he had a son Erki Savisaar, who is a Centre Party a politician. From his marriage to Liis Remmel (then Liis Savisaar), he had a daughter Maria and son Edgar. The last marriage was to Vilja Toomast (then Vilja Savisaar; the couple divorced in 2009), who is also an Estonian politician. They had a daughter, Rosina.