The fate of the Baltic countries was decided during seven days in August 1991; Hannes H. Gissurarson, a professor of politics at the University of Iceland, recalls the events as they unfolded as Iceland became the first nation to recognize the independence of the Baltic states.

The phone rang in my Reykjavik flat. It was 5:30 on Monday morning, 19 August 1991. My friend, the Icelandic prime minister David Oddsson, was on the line. “They are marching in”, he said.

There was no need to explain who “they” were. Everybody knew that the situation in the Soviet Union was highly volatile.

What really surprised many of us, however, was how reluctant the Communist Party had hitherto been to use force to quell its opponents, both inside Russia and in the many countries under Soviet rule. “This was to be expected”, I said with a sigh. “I wonder what comes next.”

David, who had formed his first government less than four months earlier, was concerned: Was this the beginning of a new Cold War? What would now happen to our friends in the Baltic countries?

Occupied for 41 years

Fortunately, this attempt by hardline communists to seize power failed. After three days, the ringleaders had all been taken into custody.

The three Baltic countries – Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia – now saw an opportunity. They had been brutally occupied by Stalin’s Red Army in June 1940 as a consequence of the non-aggression pact between Stalin and Hitler, when the two leaders divided up Central and Eastern Europe between them.

In the late 1980s, when Soviet power weakened, the resolve of these three small nations strengthened. On 23 August 1989, the fiftieth anniversary of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, a poignant and symbolic movement took place – approximately two million people joined hands forming a human chain that spread across Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. The Baltic Chain was widely reported in the international press.

On 11 March 1990, the newly-elected Supreme Council of Lithuania unanimously passed a resolution by which the Republic of Lithuania was restored. It became clear that the great majority in Estonia and Latvia also wanted to regain their independence. Frankly, they never accepted Soviet occupation.

The Baltic countries had long enjoyed sympathy in Iceland, a similarly tiny and struggling nation, but luckier in its neighbours. It is telling that in 1955 when the Public Book Club (Almenna bokafelagid) was founded in an attempt to counter the massive communist influence in Icelandic cultural life, its first publication was a translation of Estonian professor of English literature Ants Oras’s “Baltic Eclipse”, which tells the story of Soviet occupation of the Baltic countries.

In 1957, the president and foreign minister of Iceland, both committed anti-communists, received the Estonian prime minister in exile, August Rei, despite protestations from the Soviet ambassador. Again, in 1973, the Public Book Club published a translation of “Estonia: A Study in Imperialism”, by Estonian-Swedish journalist Andres Küng, about Soviet oppression in Estonia and attempts at enforced Russification.

Iceland reaffirms recognition of the Baltic states

Immediately after the Supreme Council of Lithuania had passed its resolution in late March 1990, Thorsteinn Palsson, the leader of the centre-right Independence Party, proposed a parliamentary resolution on recognising Lithuania. He was ardently backed by the deputy leader, David Oddsson, who as a young law student had taken such interest in the Baltic tragedy that he himself had translated Küng’s book.

But at the time, Iceland was ruled by a left-wing government. Its foreign minister, a social democrat called Jon B. Hannibalsson, rejected Palsson’s proposal, arguing nothing should be done that might inflame tensions between the Soviet Union and Lithuania. Hannibalsson added that Iceland had never renounced its pre-war recognition of Lithuania as an independent country, meaning it was still in effect much like its recognition of the other two Baltic countries.

Nevertheless, Hannibalsson shared Oddsson’s distinct interest in the plight of the Baltic nations, not least because his brother, philosopher Arnor Hannibalsson, had during his studies in Moscow in the 1950s made some Baltic friends who recounted numerous stories about Russian atrocities in their homelands.

Hannibalsson remained the foreign minister in the coalition government formed in April 1991 by Oddsson, who now stood as the leader of the Independence Party.

When the communist attempt to recapture power in the Soviet Union was seen to be failing, Oddsson and Hannibalsson firmly agreed with their Baltic friends that it was time to take action. On 26 August 1991, Iceland became the first country in the world to formally reaffirm its pre-war recognition of the three Baltic states. This was a mere week after David had called me in the early hours of the morning to tell me about the coup attempt.

Ceremony in Reykjavik

The leaders of the Baltic countries appreciated the Icelandic initiative, and their foreign ministers – Algirdas Saudargas of Lithuania, Jānis Jurkāns of Latvia and Lennart Meri of Estonia – flew to Iceland to attend a solemn ceremony marking the resumption of diplomatic relations.

The event took place at the historic Hofdi House where Winston Churchill had lunched during his visit to Iceland in 1941, and where Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev had tried to negotiate an end to the Cold War in 1986.

The night before, Sunday 25 August, Oddsson and his wife Astridur Thorarensen hosted a dinner honouring the foreign visitors at the prime minister’s formal residence, a comfortable and spacious home overlooking the Reykjavik Pond.

Attending the dinner were the Icelandic foreign minister, the three Baltic ministers, members of the parliament’s Foreign Relations Committee and a few others, including the tireless champion of the Baltic cause Arnor Hannibalsson; the staunchly anti-communist editor of Iceland’s leading daily “Morgunbladid”, Styrmir Gunnarsson; history professor Thor Whitehead and me, a personal friend and informal adviser to the prime minister.

It was a memorable occasion. As would be expected, everybody was cheerful, although Jurkāns had a bad cold and was therefore not completely at ease.

Over drinks before dinner, I chatted for quite a while with Lennart Meri, who would go on to serve as Estonia’s second president from 1992 to 2001. Tall, slim, balding, bespectacled, fluent in English and quite articulate, he exuded the demeanor of a Harvard professor.

He told me that he and his family had been deported to Siberia by the communists in 1941 due to his father’s role as a diplomat during independence. Meri was then only 12 years old. Despite untold hardship, however, they survived and unlike many others, they were able to return to Estonia after the war. He had made some documentaries, as had I, and we briefly discussed the charms and trappings of filmmaking.

What impressed me most about Meri was his lack of bitterness or obsession with the past. He was a pragmatist who wanted his country to join the West without irrevocably alienating its big neighbour in the East. He stressed that Iceland’s initiative was very important, but added with a smile that fortunately, our island was so far away from the Soviet Union we had little to fear.

At dinner, prime minister Oddsson gave an eloquent speech. He reminded the guests that Iceland had become a sovereign state in the same year as the three Baltic republics, 1918. He recalled his interest in the Baltic countries as a young man when he translated Küng’s book and corresponded with him, and his great relief when Moscow’s coup attempt failed.

He expressed his belief that a unique chance had presented itself and quoted Shakespeare:

There is a tide in the affairs of men,

Which taken at the flood, leads on to fortune.

Omitted, all the voyage of their life

Is bound in shallows and in miseries.

On such a full sea are we now afloat.

And we must take the current when it serves,

Or lose our ventures.

Oddsson added that God was on the side not of the heavy battalions but of the best shots, as Voltaire had observed. The Baltic visitors listened carefully. Over coffee and brandy following dinner, Saudargas commented that he had rarely heard such a stirring speech. Meri told us that his father had translated most of Shakespeare’s plays into Estonian, including “Julius Caesar” from which Oddsson took his quotation.

Meeting on 25th anniversary in 2016

Over the subsequent days, other Western countries followed suit and resumed diplomatic relations with the Baltic republics after they had endured foreign occupation for 41 years.

In 2016, on the twenty-fifth anniversary of Iceland’s initiative, the Public Book Club republished the two books in Icelandic about the Baltic tragedy by Ants Oras and Andres Küng, with prefaces and notes by me. The books are available both online and in print, while the well-written and moving book by Oras is also available on audio.

The Public Book Club also held a meeting on 26 August in Reykjavik, together with the honorary consuls in Reykjavik of the three Baltic countries. The two main speakers were former prime minister David Oddsson, now editor of “Morgunbladid”, and Estonian historian Tunne Kelam, one of the leaders of his country’s struggle for independence and at the time a member of the European Parliament.

That evening, the Public Book Club gave a dinner for Kelam in a private room at a popular Reykjavik restaurant, the Grill Market. Five guests at the memorable dinner from 1991 attended – Oddsson and his wife, editor Gunnarsson, professor Whitehead and I.

Discussion at the dinner was lively. Oddsson recalled his conversations in 1991 with other Western leaders, some of whom had been slightly annoyed that Iceland, a small country with no power to back up its public declarations, had taken the initiative to resume diplomatic relations with the Baltic countries.

Gunnarsson said that he and many other pro-American Icelanders had been bitterly disappointed in 2006 when the United States decided unilaterally to close the military base the US had operated in Iceland since 1951. The Americans seemed not to possess any institutional memory or to maintain any long-term loyalty to their friends and allies.

Kelam reminisced about Estonia’s long and arduous struggle to regain independence. In the Soviet era, he himself had narrowly escaped imprisonment because of his political activities, but he had lost his job as an editor of the Estonian Encyclopedia, working for many years as a nightshift employee on a state poultry farm.

I commented that the leaders of the Chinese Communist Party must have followed the dissolution of the Soviet Union with great interest. It was perhaps an illustration of what has been called Tocqueville’s Paradox – that a despotic regime is never as vulnerable as when it starts to reform itself. We all agreed that we had perhaps been too optimistic in the heady days of 1991, as we saw communism collapsing. It had not meant the “end of history”, but rather the emergence of new challenges.

This is a lightly edited version of the article originally published on 25 August 2021 in The Conservative; republished with a kind permission.

Read also: Estonia celebrates the restoration of independence

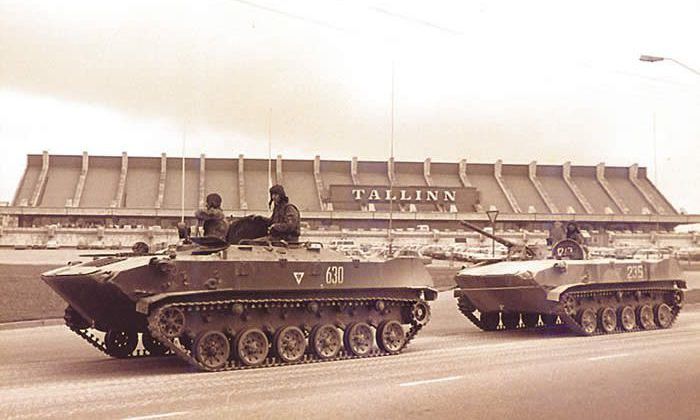

I was there with Canada’s International Trade Minister Michael Wilson as he met in Tallinn with President Ruutel and Foreign Minister Meri two weeks after the Baltic countries voted for independence. Wilson was sent to the Baltic capitals by the Mulroney government to see how Canada could help with the transition to democracy and the free market system. It was a time of high tension as Meri, who spoke excellent English and told me in no uncertain terms that translation was not necessary, asked Wilson to tell Gorbachev, when he met with him in Moscow the following day, to keep his hands off the Baltic counties. Wilson signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Estonia on that visit which made a significant difference in future relations.