Sille Pihlak, an architect and a researcher at the Estonian Academy of Arts, plays with wood to make buildings greener and more efficient.

This article is published in collaboration with Research in Estonia.

Populations are growing, cities are expanding and new homes pop up all around the world. This comes at a cost to the environment. Buildings and construction together account for 39% of energy-related carbon dioxide emissions when upstream power generation is included, according to the World Green Building Council.

Of all the building materials, aluminium, steel and cement have the biggest carbon footprint, and, looking around, most of the cities are built using those materials.

Concrete seems like a durable and cheap construction material, but as a key ingredient in concrete, cement accounts for around eight per cent of all the global CO2 emissions, almost as much as the global agriculture business at 12 per cent.

There is good news to this story – it’s called wood! Instead of releasing CO2, this material sucks the toxic gases out of the air making wooden houses behave like urban trees.

The solution to the cement problem seems easy yet building with wood is still rare as it is believed to be more susceptible to mould and water-related issues. It is a living material, after all.

Looking for perfect blocks

Sille Pihlak, an Estonian architect and lecturer who recently received her PhD, thinks we should reap the benefits of wood and design timber houses differently using other materials.

“Of course, you will get disappointed if you design concrete houses, so build them with wood,” she said. For instance, around 10 per cent of already processed wood goes to waste in the process when the windows and doors are cut out of blocks. “That’s why my research moves towards timber architecture, where material is already introduced in the design stage and takes into account the basic needs of circular economy – zero waste ideology,” Pihlak continued.

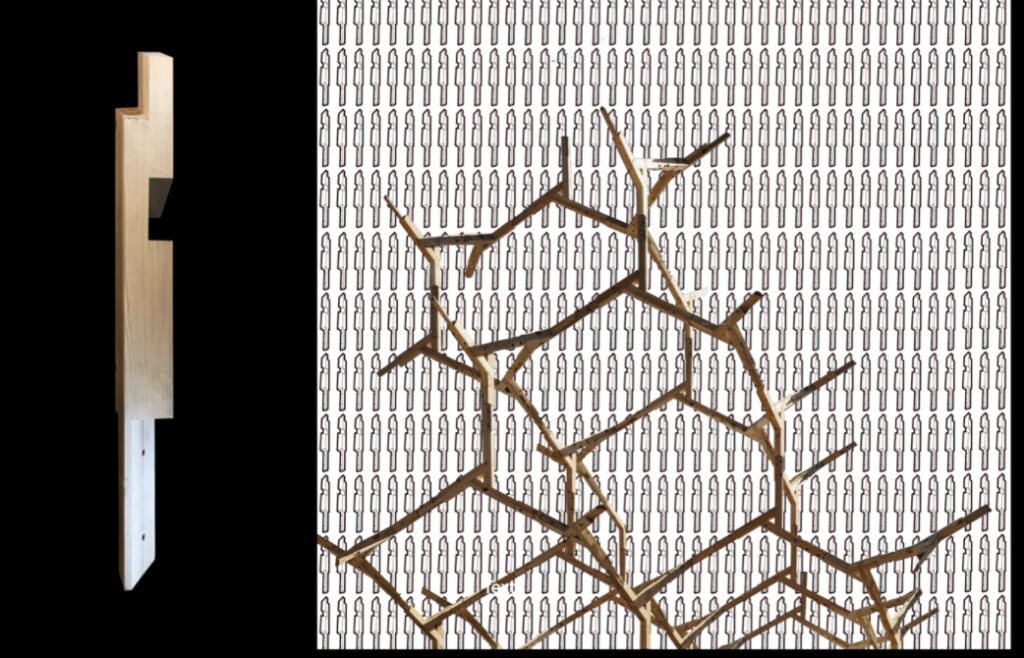

Hence, Pihlak creates more asymmetric and even circular constructions out of wooden blocks she is constantly looking for, testing and trying with. The same block could function as the roof, the floor, or even a chair. Pihlak: “I am looking for the perfect blocks!”

In her PhD, she looked at adaptive design and fabrication methods to capture the potential of live geometry and living materials such as wood.

She concluded that by working closely together with the engineers and fabricators in a non-linear, looping manner, architects can create a more efficient design that could also be less wasteful. The process would involve jumping back and forth and piecing the construction together in a close cooperation between different experts. The particularities of working with a natural living material can thus be taken into account throughout the whole process.

Architects should be “master builders”

She also showed the importance of repetition and modularity when designing large-scale, wooden buildings. Pihlak believes contemporary architects should regain their position as “master builders,” being able to discuss from machinery to material qualities, to understand the engineering logic behind the form.

“The timber house manufacturers already have powerful robots in their factories, although they mostly use them for the simplest tasks,” said Pihlak. “Architects shouldn’t be mere sculptors anymore. Instead, they should curate the process and have the role of in each stage of the production chain.”

In times of automation, creating those Lego blocks is easier than ever.

As a practicing architect in PART and a co-founder of the algorithmic timber architecture research group in the Estonian Academy of Arts, Pihlak particularly likes to illustrate their ideas in human scale objects – as bus stops and installations. They can be modified and played around with – and placed in public places to promote the use of wood and new spatial qualities.

Estonians are among the leading timber house builders

Pihlak, who did her master’s at the University of Applied Arts Vienna and also studied at the Southern California Institute of Architecture, is not alone in this fight for more green construction. The European Union is promoting the use of wood as a building material, calling the movement a New Bauhaus Initiative.

In autumn 2020, Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission, launched the movement to collectively brainstorm for new ideas for future homes. “People should be able to feel, see and experience the European Green Deal,” she wrote.

One way to feel that, in her opinion, is via natural materials such as wood. This makes Estonia the perfect place to start with.

Estonia is one of the leading exporters of timber houses in the world. Over 90 per cent of the Estonian logged constructions are exported, mostly to the Nordic countries. They become traditional-looking mountain houses or steamed saunas.

These simple constructions that have been built for centuries are now being mass produced and shipped out for profit. “Ultimately, timber house makers compete over who gets to produce cheaper goods,” Pihlak said. “But you can only bring the price down to a certain degree. Many of the producers are now rethinking their values and goals.”

Pihlak’s testing ground is the whole Estonian timber industry. It is easy to gain access and cooperate with different experts in this small country with a relatively flat work hierarchy. Her research practice PART has cooperated with one of the biggest local factories – Arcwood.

“To create houses efficiently and fast, it should have a certain logic,” Tarmo Tamm, a board member of Arcwood, said. The kind of modularity that Pihlak is proposing, is a good starting point for this, in Tamm’s opinion.

Public sector lagging

Slowly, the interest in more natural materials is trickling to governmental institutions too. The Estonian environment ministry is erecting the first wooden government building that will also function as a climate change competence centre. Martin Kõiv, a senior official at the ministry, spent eight years striving for this to happen. He said it was difficult to convince the government to allocate money to this rather innovative project.

Kõiv, who visited various wooden house conferences and spoke to many experts around Europe, is a big fan of wood. “I believe that wooden houses are making a comeback because I don’t see any other logical explanation to why people should prefer concrete to wood,” he told Research in Estonia.

Kõiv worked with Pihlak and her teaching partner, Siim Tuksam, who even created a university programme for students to come up with ideas for the government building. At the end of the semester, Kõiv and other government representatives were invited to evaluate the results.

Sadly, the public sector, Kõiv said, is still lagging when it comes to making use of more natural materials. “We have enough ideas and experts in Estonia to create great things, but we don’t yet have enough customers for bold ideas,” he concluded.

Slowly though, it seems that wood is making a comeback and while we worry about the plastic straws and toys, let’s not forget to look at the much bigger elephant in the room – the room itself.

Cover: Professor Sille Pihlak at the bachelor degree jury of the interior architecture department at the Estonian Academy of Arts. Photo by Tõnu Tunnel.