Ivo Fridolin, a professor at Tallinn University of Technology, has developed a new sensor that should increase the survival rates of kidney disease.

This article is published in collaboration with Research in Estonia.

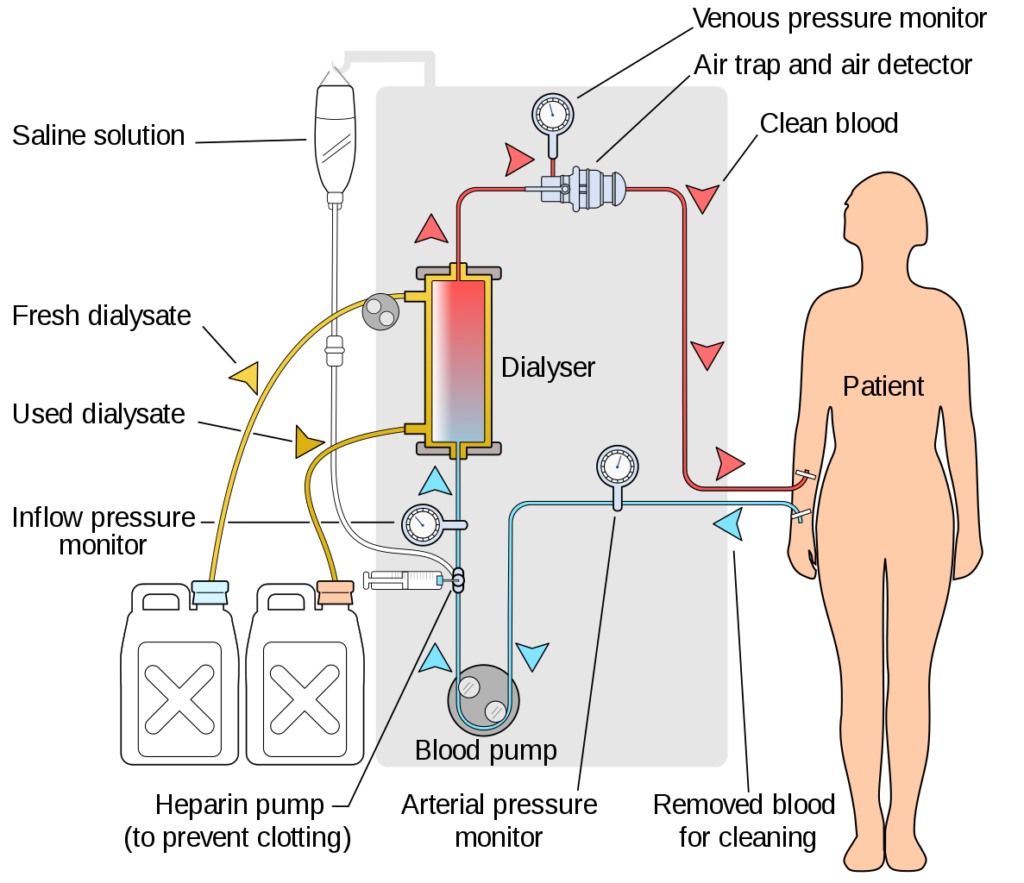

Chronic kidney disease is a global problem and is anticipated to become the fifth leading cause of death worldwide over the next two decades. And while artificial kidney therapy, also called haemodialysis, is used to treat end stage kidney disease, monitoring its efficiency remains cumbersome, according to Ivo Fridolin, a professor at Tallinn University of Technology – also known as TalTech – and the head of its Centre for Biomedical Engineering.

“This is a time-consuming treatment with side effects such as dizziness and hypotension,” Fridolin said during a recent participation at the Life Sciences Baltics 2021 conference, which was held virtually this year.

For four hours, three times a week, end stage kidney disease patients undergo artificial kidney therapy, which requires about 150 litres of water per treatment. They also must ascribe to a complex medical and dietary regime. “This is one of the most extensive chronic disease treatments, with a heavy burden for the environment,” Fridolin remarked.

As such, surveillance of the effectiveness of these treatments is essential to achieve best care and resource management, Fridolin said in his talk. Often recommendations related to dialysis doses are based on blood samples drawn from patients. However, other methods have been developed for monitoring dialysis at clinics and at home, based on optical and conductivity-based sensors attached to dialysis machines.

There exists some criticism of these approaches in that they are too simple or measure only a few markers to gauge the effectiveness of dialysis, though, and a proposed solution is to move toward multidimensional measurements of dialysis adequacy. Fridolin announced that this is possible and that he and researchers at TalTech have developed a device that he referred to as “spectrophotometric eyes” that can be used to monitor the removal of diverse types of uremic retention molecules.

A unique sensor

This device, called the multicomponent uremic solute monitor, or MSM sensor, combines ultraviolet absorbance and fluorescence imaging technology for monitoring urotoxicity. This optical sensor is connected to a dialysis outlet, where all spent dialysis is monitored as it passes through during a treatment session in real time.

“This allows us to generate real-time concentration profiles for different uremic solids,” Fridolin commented. He said that an internal comparison of data from the MCM monitor to data generated using conventional methods showed a high level of congruence.

The sensor can also be used to calculate removal ratio profiles, and total removal of uremic solutes’ profiles for different molecules belonging to different uremic toxin groups. This can “give a fuller picture of what is happening during dialysis,” and also serves as a means to gauge the performance of a haemodialysis machine. It also enables the collection of longitudinal data for a single patient that can be used to plan further clinical interventions for haemodialysis therapy, Fridolin noted.

The technology is patented

Much of the work on the monitor was performed within TalTech’ Sensor Technologies in Biomedical Engineering Research Group, called SensorTechBME for short, which Fridolin heads. SensorTechBME belongs to the Estonian Centre of Excellence in ICT Research, or CoE EXCITE. Its main research goals are around developing new technology sensors and algorithms for biomedical engineering applications, with a focus on biofluid optics, uremic toxins, and dialysis.

The technology has been patented and is being commercialised by a company called Optofluid Technologies, of which Fridolin serves as CTO. In his talk at the conference, Fridolin said that the advantages of optical online monitoring using Optifluid’s device include online real-time monitoring of removal, multicomponent monitoring, and no need for blood samples of chemicals to achieve results.

“There are also low running costs and operational reliability, the method is safe for patients and users, and all measurements are done optically on the machine without interruptions of treatment,” Fridolin said.

A clinical validation completed in Sweden, Spain and Belgium

According to Crunchbase, Optofluid was founded in 2012 and was awarded €2.8 million to undertake a Horizon 2020 project in 2017.

The company claims its MCM reader is a step forward in measuring toxic molecule removal during the course of artificial kidney therapy in real-time and offers real-time data on removal of protein bound molecules and middle molecules, in addition to more traditionally used markers, such as urea and uric acid. As this enables nephrologists and nursing staff to improve outcomes of patients and better the care of patients, there is the potential to lessen mortality of patients undergoing treatment, which is currently high.

“The cascade of improvements in the therapy management of the patient leads to a potential of up to 20 percent increase in survival,” Optofluid claims on its website.

According to additional information provided by Fridolin, Optofluid has developed two modifications of its sensor. It recently completed a clinical validation of the tool with hospital systems in Tallinn, Estonia; Linköping, Sweden; Madrid, Spain; and Gent, Belgium. Fridolin said in a follow up email that OptoFluid continues to develop the MCM sensor, and that it is not yet commercially available.

“Everything is uncertain due to the pandemic, but our hope is that it will be commercialised as soon as possible, realistically within two years’ time,” Fridolin stated. He added that another clinical study should commence later this year.

Cover: The models of kidney, brain and nerves. Photo by Robina Weermeijer on Unsplash.