The former president of Estonia, Toomas Hendrik Ilves, says in a wide-ranging interview with French journalist Violaine Champetier de Ribes that the Estonians’ entrepreneurial culture comes from a hunger for success they developed during the Soviet occupation – being poor and having nothing to eat, and at the same time watching the food commercials on Finnish TV, seeing how much better off the Finns were.

Thirty years ago, on 20 August, Estonia restored its independence. As the country celebrates the three decades anniversary of retrieved freedom, I met the former president of Estonia, Toomas Hendrik Ilves, who was in office from 2006 to 2016.

The primary instigator of Estonia’s digitisation, and many other things, was born in Sweden in 1953, where his parents had found refuge in 1944 as they were fleeing the Soviet takeover of their native land. His family later moved to the US, where he got a break-through experience with programming in 1971. Later, he studied experimental psychology at Colombia University and spent time writing essays on the Estonian literature.

In the late eighties, he became the head of the Estonian bureau at Radio Free Europe in Berlin at only 34. After the restoration of independence, he became the Estonian ambassador in Washington in 1992 and the country’s foreign minister in 1996. Since then, his life has been triggered with Estonia’s path, as he nudged its frog leap and pulled out all his energy to bring his country back into the western world.

Ilves is never afraid to speak his mind. He is always in for a good joke and never stops evangelising about the digital state’s benefits and what to do to keep Estonia in the game.

From your point of view, what are those last 30 years’ most significant achievements in Estonia?

The success of Estonia’s innovation is one part of it. It is not just Estonia being successful, but it is about pioneering a different way of governance.

From my point of view, the last 30 years’ most significant achievement in Estonia is that we are back in Europe, which was not at all the attitude in the 1990s in the West. There was this official “nonrecognition policy”. Otherwise, it was all about “this former Soviet Union country”. By the way, I hate this reference to the “ex-Soviet Union republic” when it comes to Estonia. I see it so often in the German or the French press. Taking France as an example: in 1975, nobody would refer to France as a former Nazi-occupied country. Here, you don’t have grey people living grey lives in grey houses. In thirty years, we have undertaken this huge transformation. Estonia is now a very vibrant society and probably far more vibrant than many countries in the West. We are the West culturally and politically.

In 1996, when I came back here as an emergency foreign minister, I said, now we forget all this negative stuff, and we’re going to go to NATO. But we have to get in the EU first because otherwise Germany, France, Italy, the UK won’t want to let these former Soviets in here. I thought it was logical; despite being a major brain wave, it met huge opposition in Estonia itself.

The formal recognition of the country and getting Estonia in the European Union is something I count as one of the most important things that I spent time doing as a foreign minister before being president. Today we’re less corrupt than most countries in the European Union. We are even ahead of France when it comes to the Transparency International corruption index.

On the digitisation side, I am, of course, glad it has worked out! I had this crazy idea in 1993/94 because of my background: I learned to program in the US when I was 15 years old in 1971. That’s 50 years ago now! It was a one-year-long experiment. I was one of the guinea pigs for a teacher who was doing her PhD in math education. She had this idea that maybe we can teach kids to program. She rented a teletype machine with perfotape and then we had this big telephone modem. You would stick a phone into it then you could connect to a mainframe 40 kilometres away. That’s how I learned to program in BASIC (a simplified version of FORTRAN). After that experience, I have never been afraid of computers. Later, when I went to university, I took a side job as a programmer in a lab. That was about all I did with what existed. I was just never afraid of it. I earned my first PC in 1982.

At the end of my presidency in 2016, I was invited to come to Stanford [university]. I moved back to Estonia in June 2020. When I moved back here, an article in the New York Times (COVID was three months old) said a backlog of 1.7 million US passport renewals was unfilled because COVID had shut down everything. In Estonia, to renew my passport, I apply for a new passport online. I don’t have to bring physical papers because they already know who I am. All I must do is submit a new picture (because few years have passed). I think this is an excellent example of what we have accomplished, and by we, I mean the whole country. And, of course, the entire Estonian startup scene is part of this as well. I went to the big party on 7 July for Wise, the international money transfer service founded by two Estonian entrepreneurs in 2011. It entered the London stock market, valued at €9.3 billion.

Thirty years later, here is where we are thirty years later, and journalists are still writing: Estonia, the ex-soviet country. Give me a break!

What made Estonia go digital?

If you go back to 1938, which is the last year before the Second World War, and look at the charts from the “Cambridge Economic History of Modern Europe”, you can see that Estonia’s GDP per capita was higher than Finland’s. We were doing better than Italy, Czechoslovakia, Ireland, Greece, Hungary, Poland, Spain and Portugal. In 1992, Finland’s GDP per capita was eight times higher than Estonia’s. We were poor and backwards. That’s what 50 years of communism will do for you, as one of the benefits of communist rule is that it slows down development for real.

In the meantime, the West as it was, or the “non-occupied countries”, were ahead of us. Everyone had been building infrastructure for the last 50 years, Germany, France and Finland, and they were moving forward. After five decades of lack of infrastructure development and the rule of law, and all this stuff, we just had Soviet crap, bad roads and a telephone system from the 1930s. It was not a pretty picture. Even if we tried our best to rush up, we would never catch up to them with four-lane highways and high-speed trains. When it comes to things like building and construction, you always are stuck in Zeno’s paradox (Achilles races to catch a slower runner – a tortoise – that is crawling in a line away from him. No matter how Achilles tries, he would never catch up with the tortoise – editor).

Back in 1992, we were looking at the situation and asking ourselves: How are we going to get out of this? Knowing that once we were able and now, we are here. All the people had different ideas. Some wanted to keep communism, and others wanted to become Singapore or Hongkong, and so on.

Another thing happened in 1993. In 1989, Sir Tim Berners Lee had just invented the world wide web. Or, more precisely, the tiny HTTP (or hyper-text transfer protocol, the basis of the internet – editor). There wasn’t much functionality, however, until Marc Andreessen, then a postdoc at the University of Illinois, came out in 1993 with Mosaic’s first-ever web browser. Unlike web browsers today, it was a local upload. You had to buy it for USD29.95 or something like that in this store called RadioShack. You would get like seven floppies, and after uploading the floppies, you had access to the world wide web.

I looked at this and saw an area where we were on a level playing field as everyone else was at the same place. I thought, let’s push this; we should go into it because we were victims of Zeno’s paradox in development on everything else. Back then, I said, “This thing is going to be big anyway.”

The question was, how are we going to do this in Estonia? Lots of people were involved in this. Estonia was very good at doing computer stuff, so I said, “Well, let’s put all the schools online.” If you want to start early, start with the kids, that was my input. I was lucky, thanks to the brilliant and courageous education minister we had in 1995/96, Jaak Aaviksoo, a PhD in astrophysics. He found that it was a good idea and pushed this through in the government. The project was then accepted by the government, even though it sounded crazy to them. We put computers in all schools and connected them all, and by 1999, all the schools in Estonia were online. It was given the name Tiger Leap.

Getting all schools online had a considerable effect many years later. In 2016, when asking people who had created big startups how they started, they would say, “I was a kid in your programme.”

How did your vision of the Tiger Leap programme come up?

Originally, I just read many books, had no vision and had no clue other than saying “Well, digitisation is the way we should go.” I knew we had the base allowing us to have a good start. By the Soviet standards at the time, Estonia had a developed IT sector. The young techies who built Skype were from families whose fathers and uncles were professors or computer scientists.

I met tremendous opposition. The most significant opposition came from the teachers. In the weekly teachers’ newspaper, someone would write an article about how stupid this was almost every week. Strictly, it’s understandable because this is something where the kids will move much more quickly than them. A 50-year-old teacher will have problems with programming while a 15-year-old kid won’t, and you don’t want your students to be better than you.

Do you think everyone should learn to program?

I don’t think everyone has to be a techie, but I think everyone should learn programming to have a basic understanding of what it’s about. There’s nothing really mysterious. It’s just logic. It is necessary in the modern world. You have to understand what people are talking about and how it works so you don’t have mystical beliefs.

Last year, Estonia ranked number one in Europe on the Pisa test of students ability in science and math; we’re number one or two every year. We compete with the Finns, but we’re still not as good as the five Asian countries always ahead of us. Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan and China are ahead of the West while the US is way behind.

What was the first primary step?

In 1999, Estonia was advanced enough to understand that a digital society cannot be based on a previously existing solution. We were facing three crucial problems: how can you provide a unique secure ID, deliver valuable services and ensure data integrity?

Let’s talk about the first one: you need a unique and secure digital ID. Make sure no one else is going to be you. It was summed up brilliantly in a 1993 cartoon in the New Yorker. There are two dogs. One dog is sitting in front of a computer, and he’s telling the other dog, “On the internet, no one knows you’re a dog” – this sort of sums up the problem of identity on the internet.

In 2021, people are still using email plus passwords. When I buy books on Amazon, I use an email address and a password, but that’s ridiculous. If you want to digitise the private or public sector, you need a two-factor authentication with a unique identity and encryption. So, we did that, and that was the beginning of Estonia’s digital journey.

Why do other countries don’t do it? First, they don’t have the political will to issue a unique mandatory digital identity. Even though the eIDAS directive mandates it for the EU from 2017, they break down because they don’t make it compulsory. After all, you must make digital ID mandatory. It would help if you made it mandatory because you will not get any new services development unless it’s obligatory. If it’s voluntary, 15 to 25% of the population will get themselves and use a digital ID, but 85 to 75% will not. If you’re a government or public service, you look at this and say, why should I invest in developing a digital version of a service if only 15-25% of the population will use it? You are not going to put that money in there because the potential user size is 15-25%. On the other hand, if you’re a citizen and not in the 15-25%, you ask, why should I get a digital ID if it doesn’t give me anything because there are no useful services? It’s a Catch-22.

If everyone has a digital ID, on the other hand, it drives the public sector to develop services. The user base increases, so you get to the point where 99% of taxes and 99% of prescriptions are digital in Estonia. We would not have developed digital prescriptions if only 15% of the population had a digital ID. Then you end up with this massive difference in the quality of public services.

I noticed this gap when I moved to Stanford as a visiting scholar in 2016, I had to register my daughter to school. I had to drive to the school headquarters to give them my electricity bill to prove I live in the town, show them my passport with the visa, and provide a DS2019 form saying how long I will stay at the university. The woman there filled all the paperwork by hand for 20 minutes! I was in the middle of Silicon Valley, the Mecca of IT, not a remote lost place. In Estonia, they’ll send me an email saying: your child now is seven years old, it’s time to register for school. Then I will go on online and register my child.

How did that lead to pioneering new ways of government?

Having accepted that we would go digital in this country, people far smarter than I am said, if we want to go digital, we must develop something that works. This quest went to pioneering a new way of government.

How did different ideas come up in government or politicians? I’m not sure people initially had new ideas in governance. I don’t think they thought of it as a new way of governing. They were focusing on solving problems. That’s how we came up in 2000, with an interoperability platform for existing decentralised databases and a data exchange layer. Both public and private sector actors can use this solution that remains unadopted by most countries in the world 20 years later. If you look at it now, you realise that Estonia has wholly changed how governance works. It brought parallel processing to governance which had never been done since bureaucracy always functioned on serial or sequential processes. This entirely distributed architecture we call X-Road is what made Estonia take off. That’s the digital state’s second pillar.

In early 2000, a friend of mine was one of the designers of X-Road. The software is not the most challenging part, even if the distributed data exchange layer is excellent. The hard part is, what do you connect to what? Who can see what? He was working on this challenging part when his kid was born. He went through the agony of going from one office to get the birth certificate to another to get the child on the population register, then to another one again to get the baby’s health insurance, and then to register the newborn with the municipality. After his experience, he said, I don’t ever want to do that again. So now, since 2001, if a child is born in Estonia, the hospital asks the parents for his or her name. Once they get the baby’s name, they inform the population registry, which issues an ID number. The information goes straight to the health insurance, and the local government is informed. This brought parallel processing to governance which had never been done since bureaucracy existed.

Bureaucracy was invented 5,000 years ago because a warlord needed to have a division of labour. The notion of states and how they work started then. Probably, some warlord managed to subjugate enough people and became a king. But once he had a state or a proto-state, he needed to run it. He needed to have warriors, but the soldiers would not be good warriors if they grew wheat in the fields. Then he needed someone to make sure the grain would go to the soldiers, so he had bookkeepers. That’s how you end up with an administrative class bureaucracy. As long as the entire process was physical, clay tablets, leather or paper, each country was a serial process. The parallel process we use has changed the nature of bureaucracy. It is also why we have this “once only” rule in Estonia, meaning the government can’t ask you anything it already knows.

The whole distributed architecture gives security. Do you remember the Exxon Valdez oil spill? After the oil ran from the world’s most giant tanker causing enormous ecological measurement, tankers would then on have compartments so if an accident happens, you will lose some of the oil but not all of it. That’s the principle of X-road. Everything is stored separately and accessible through your ID. We do not have one extensive database.

It also has a huge effect on eliminating petty corruption. As it is used by the ecosystem (banks, service providers), it brings the trust needed to get citizens to vote online. Elections online-only work because of trust, and that trust comes from the ecosystem where I do all my daily transactions: signing documents and doing whatever with the system. In the last twenty-five years, we have offered e-voting in national, local and EU elections. The ID card I use to vote is the one I used hundreds and hundreds of times for my daily life, such as banking and income tax, and nothing has ever failed. But it is important to keep in mind that online elections only work if you have the whole system bringing trust and a high level of security. You know the security capacity is high because you have tested it by yourself every day.

Do you think Estonia has reached its innovation glass ceiling?

I think we can go much further. There are experiments on using AI in public services. For corporate taxes, for example, it will get rid of accountants. Instead of quarterly reports to the tax authority by a company, real-time online monitoring is possible as we already have your file, your VAT, indeed every business transaction, income as well as outgoes etc. If the corporate tax department sees that your business is not going well, and it can say, let’s discuss it, how can we help you? This is taxation as a service. Fine-tuning things like that are possible in Estonia. The essential things are not available across borders, and that’s where Estonia’s actual glass ceiling is. So, the real problem today is not where weare but where everyone else isn’t.

If you want to make the EU popular again, the natural big step now is integrating digital services across the European Union. We have one case with digital prescriptions.

We have around 7,000,000 Finnish visits a year. Ten years ago, I proposed to the Finnish president to organise a cross-border solution for prescriptions. We are using the same software, and we both have digital prescriptions. It took nine years of negotiations (for example to avoid arbitrage as Finnish and Estonian governments subsidise different medicines to a different degree for different age groups). I give this example: if you have high blood pressure in Finland, you will get this x medicine. The Finnish government pays 40% of this x medicine. Estonia on the other hand might pay for 70% of the x medicine. You can’t have people traveling to get cheaper medicine. The idea is to organise how you compensate and be sure the money goes in the right place. You must pay what it costs in your own country. Otherwise, the Finns will come over to buy not only cheap alcohol but also cheap medicine!

The next European move should not only be about cross border digital prescription, but it should also work for medical records. If I get sick in Greece and I go to a doctor, I’m in trouble – even if I access my medical records digitally, they are in Estonian, not Greek. But with cross-border digital services, If I authorise the doctor to look at my medical records, he can see that I am allergic to this or that and my medical history. I would approve the Greek doctor to access my medical records. He would get them already translated in Greek because that’s a no-brainer with AI, especially with medical records. Each EU country would use the same form.

Is privacy the third pillar of Estonia’s digital state?

The third thing to worry about when you go fully digital is not really privacy but the far more important issue of data integrity. Privacy is about someone else, someone unauthorised to look at my data or use it. Integrity is about not allowing anyone to change my data. If someone publishes my bank account, my medical records etc, it might me embarrassing but if they change, say, my medical records, it could be fatal. It took a while for us to get there, but we have had it since 2008. Going fully digital means everything is digital. We do not publish a congressional record or any document with all the laws passed; they are only in digital form. It is similar to court cases, you don’t have to go to the library to look for it. You just have to go to your computer. But you can imagine the chaos if someone goes and changes a law or a court decision.

The fundamental issue in a digital society then becomes data integrity, meaning no one has changed the data. Whenever I talk in Germany or France, people keep asking, what about privacy? Privacy is important but not as much as data integrity.

If someone publishes my blood type, it’s kind of annoying on its own, but that’s all. If someone changes my blood type in my record, I could be in real trouble. If they try a transfusion on me in hospital, and I get the wrong blood type because they read it in my file, I could die. If someone logs in to your bank accounts, it’s unlikely they’re going to increase your accounts; your money is more likely to disappear. You must worry about data integrity. In this country, we use blockchain (I hate to use the word). We do it through a distributed ledger which is a much more precise term, and we use KSI (keyless signature infrastructure). When people talk about privacy, we have a key element involved. Every transaction is logged, which means it enables us mutual, reciprocal transparency.

Data integrity and security are imperative for us. In the past thousand years we have been invaded about an average of twice a century, and during the 20th century, it was up to seven times.

After the Fukushima meltdown, either due to the tsunami or the meltdown, the Japanese lost some small portion of their national data, Estonia entered discussions with Luxembourg. We appealed to the Vienna Convention on diplomatic immunity and extraterritoriality to have a backup server in Luxembourg. We don’t have a person in Luxembourg, but we have a server. It’s just an embassy with extraterritorial rights. A 24/7 online dedicated line of encrypted data flows from Estonia with all critical national data: property records, laws, population registry. If we’re invaded again, we will have a virtual record of everything at the moment of invasion. I would also recommend countries that live in seismically active areas to do the same.

With seven unicorns founded by Estonians and/or in Estonia, the country is number one in Europe for unicorns per capita. Where does this entrepreneurial culture come from?

A part of it is being hungry. People were very poor. Estonians could watch and understand Finnish television. They looked at life there and compared it to life around them, which led to this hunger for success.

I remember a friend of mine told me how in the late 80s, if you would go to the food store, they only had pigs’ heads with the cheeks cut out, so they had almost no meat. When you watched Finnish television, you could see this very obnoxious company commercial showing cuts of beef and pork with the prices – while you would be sitting there looking at this red meat, eating another disgusting meatless meal. It only had an effect in Estonia because elsewhere, people couldn’t see the innovation (behind the Iron Curtain).

The first entrepreneur kids wanted to be like the Finns. Then Skype changed everything. This incredible success wasn’t even because they all got rich. It was the attitude: we were this poor little cold and rainy backward provincial sort of corner of Europe, and then, suddenly these four guys invented the voice over the internet protocol or VOIP. Niklas Zennström owned the company, but these four guys invented a solution that became within months a worldwide sensation because everyone was using voice over the internet protocol. That meant we didn’t have to move out of Estonia to be a success, we could do something here, and that studying math is good! Countries that have a strong emphasis on science do better.

Is it possible to have a decentralised state architecture in a centralised state such as France?

You can have a decentralised architecture in a very centralised state. The point is that you don’t have a single database, but everything must be connected. The beauty and the benefit of that and why people trust it is because every transaction is logged. We have mutual, reciprocal transparency. We are transparent. You can see who’s looking at your data. For example, property records are all public in Estonia; I know it’s kind of weird for lots of people, especially in southern Europe. People can go look at what I own, but I can see who is looking at my property records. It works both ways. When I was in office, I’d go see who’s been looking at my data once a month. It was always journalists from the yellow press. They wanted to see: did he buy anything? I’m not even sure the journalists who would go look at my records knew that I could identify who they were. It’s open information.

In contrast, the paper system was best exemplified by the experience of the Formula One racing driver Michael Schumacher who was in a horrible ski accident and in Switzerland in 2013. Within hours after his accident, the largest tabloid in Europe, Bild Zeitung, published pictures of his skull and all the reports going on with him. I think this is kind of a major violation of privacy that could never happen here. Even the people in health care who have access to your data have their access logged. We would have found out very quickly who accessed and linked the data. While in Switzerland, at least then, you can take a paper document or record, put it in a photocopy machine, and then put the paper back. And no one knows who did it.

You worked on the European cloud project many years ago. What do you think about how the project is going?

I was asked to run that task force. I got the very strong feeling that the idea was to create a less effective and more expensive cloud in competition with AWS. It is a protectionist attitude. The work that is going on now, based mainly on French and German cooperation, is defensive. I’m not an economist, but protectionism generally doesn’t work, especially when it comes to tech if you’re offering inferior products and defending them by protectionism, you are just going to fall behind.

I have nothing against fighting the GAFAs based on their taxes policy or the behaviour of Facebook stealing and using your data which is highly offensive. I just think it’s a much minor battle compared with the technological dominance that we see coming out of China. Their strategy is basically colonialism as they are moving into Latin America and Africa in a big way. I think Apple should be taken out of GAFAs simply because they are pro-privacy (this is what the whole big fighting between Facebook and Apple is about). The goal of the European Union to take this protectionist attitude and digital services act is much more about fighting the US than offering digital services to Europeans.

I would even go further. Aside from local problems, and we have many local problems with Russia; Russia is a tornado that comes and goes. When we look at where the world is heading, the real threat is China, the level of technology there is amazing. You just go into an airport, and facial recognition gives you your ticket on your phone. The beggars have QR codes you can use to send him five yuan. Weibo payments are much more accessible. There’s absolutely an issue regarding freedom. You’re not freer because of papers; the problem is that they also apply it to authoritarian systems. There’s no reason why we can’t have a democratic liberal democracy digital society.

The big issue now is 5G. You don’t want to mess with 5G. 4G is just hardware, but 5G works with hardware plus software. You can always change the software easily. You look at it and see nothing wrong, and then three hours later, they can change the software and listen to everything you’re saying, for example. The problem in Europe is that two companies are producing 5G – Nokia and Ericsson. Their solution is more expensive than Huawei. Last year at the Munich security conference, right before the COVID-19 outbreak, the US Secretary of Defense came to say we cannot use Huawei. So, I asked the first question: I said, very nice, we can’t use Huawei, but are you prepared to subsidise the production of Nokia and Ericsson’s 5G because they’re too expensive to compete with China’s state-subsidised Huawei? People are installing Huawei 5G because it’s cheaper and more affordable. After all, the Chinese state subsidises it. Now, if, Mr Secretary, you don’t want Europeans to use Huawei as you Americans don’t produce 5G, why don’t you sponsor Nokia and Ericsson to make them competitive? He said that’s an excellent question. And that’s where we are.

Your parents fled the Soviet invasion in 1944, and you were not born in Estonia. Did a solid patriotic commitment guide you?

I think it was more a political commitment being against political repression. My parents fled because people came and started killing Estonians and deporting them. What kind of government does that? It’s much more a matter of believing in freedom and liberal democracy than just about Estonia.

My people and my relatives were deported. I grew up knowing we were living in the United States because bad people came into our country. I remember one of my great experiences when I was six years old. The teachers asked everybody in the class to show us where we were from. There were Japanese kids, Polish kids, lots of Italian kids showing their country on the map. When I went there and showed them Estonia on the map, they said, “Oh, you’re from Russia!” And I went on saying no, I’m from Estonia.

Simply because I’m pro Estonia does not make me a nationalist, but I do like this country. I pushed things that I thought I could do, that’s all. I was in this position where I could affect things good for our country; I could say, OK, let’s do this, and we did it. It’s about having an opportunity to do things rather than using them, which is the problem with too many politicians today.

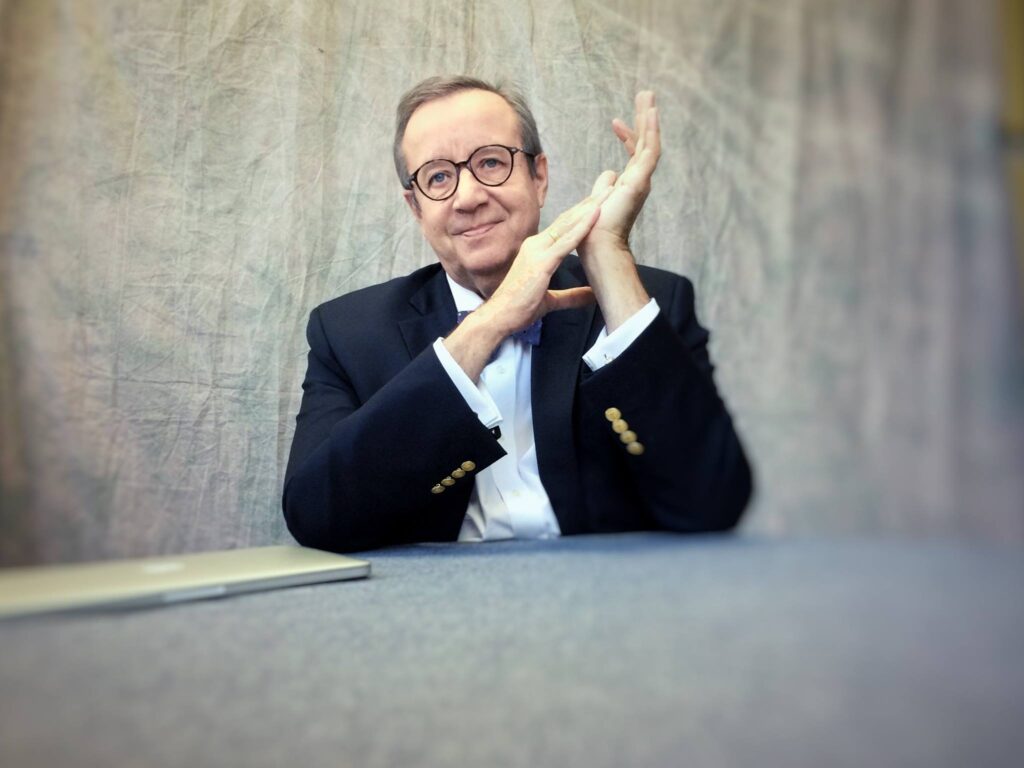

Cover: Toomas Hendrik Ilves with his laptop in 2017. Photo by Kaire van der Toorn-Guthan.