On 29 August 2016, the Estonian parliament (Riigikogu) will vote on the country’s next president. At a time of uncertainty in international affairs, an Estonian president that is firmly focussed on foreign policy will certainly remain an unwavering asset in the effort to maintain Estonia’s national security, writes Eoin Micheál McNamara.

This article was first published in the Baltic Bulletin.

On 29 August 2016, the Estonian parliament (Riigikogu) will vote on the country’s next president. This election comes at a time of considerable uncertainty surrounding the security situation in the Baltic Sea region. In the Estonian political system, the presidency is weak in terms of legislative and executive decision-making power. Nevertheless, a president that chooses to be prominent in foreign policy matters can be a valuable asset in convincing Estonia’s allies to further support its national security priorities.

To highlight just how effective two internationally focussed Estonian presidents have been in the past, this article will compare the considerable foreign policy achievements of presidents Lennart Meri (1992-2001) and Toomas Hendrik Ilves (2006-2016), before analysing the foreign policy credentials of the possible candidates seeking election in August 2016.

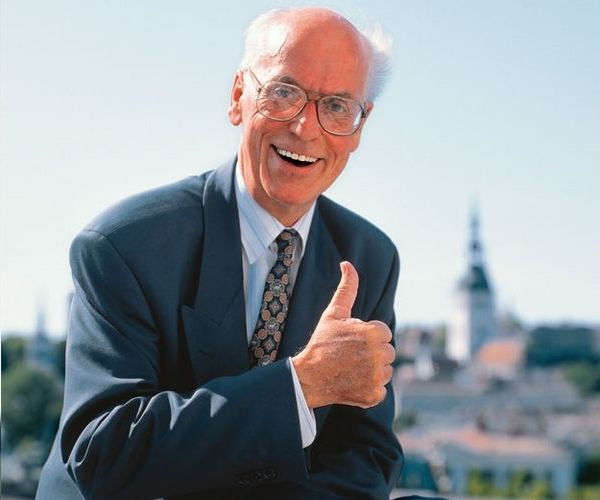

Lennart Meri: navigating a Western path

Lennart Meri, Estonia’s president following the country’s restoration of independence in 1991, set a distinguished precedent by placing prominence on foreign relations within the Estonian president’s portfolio of duties.

Meri, who was elected president in 1992, had previously served as Estonia’s foreign minister between 1990 and 1992. He oversaw the creation of a Western-focused Estonian ministry of foreign affairs that attracted young English-speaking staff over Soviet-era bureaucrats and is credited as one of the main architects of Estonia’s EU and NATO membership.

Estonia’s presidency is a weak institution in terms of legislative and executive power, but it has what Richard Neustadt famously described as “the power to persuade.”

As president, Meri spearheaded the Estonian delegation that negotiated the withdrawal of the last remaining post-Soviet Russian troops stationed on Estonian territory during the early 1990s. The favourable outcome was not a foregone conclusion. Meri’s diplomatic skill and standing were crucial to convincing Russian president Boris Yeltsin to withdraw all remaining Russian military units in Estonia by 31 August 1994. Russia’s withdrawal removed a major obstacle to Estonia’s quest for NATO membership.

“Estonia’s presidency is a weak institution in terms of legislative and executive power, but it has what Richard Neustadt famously described as “the power to persuade.”

During the 1990ies, Meri’s diplomatic efforts helped foster stronger links between a newly re-independent Estonia, northern European capitals, the UK, and Germany, as well as with US presidents George HW Bush and Bill Clinton.

Understanding that a stable European security order would be to Estonia’s benefit, Meri’s approach was to discuss with Western diplomats the security matters of wider transatlantic concern. Meri would then illustrate Estonia’s position and context within the wider strategic environment. Estonia’s security interests were brought to the attention of Western partners, but Meri’s discourse indicated that Estonia also wished to become a contributor to security within the wider transatlantic web and not just a problematic consumer.

Meri selected many visible forums to make the case for NATO’s “open door” enlargement policy. He frequently raised the moral argument that cooperation between Russia and the West should not come at the cost of denying the democratising Baltic states their opportunity to gain collective security. This argument clearly resonated with the Clinton administration’s idea of “democratic enlargement” as one purpose for NATO’s eastern expansion.

The Ilves era: expanding international status

Arnold Rüütel, a former Soviet apparatchik who supported Estonia’s independence struggle during the late 1980s, was elected as Meri’s successor in 2001. Rüütel held a poor command of the English language and was often criticised for his passive role in foreign affairs.

As a consequence, some among Estonia’s younger generations and its expanding middle class perceived their president as an “embarrassment internationally.” In the 2006 presidential election billed as a “clash of the eras,” Toomas Hendrik Ilves defeated Rüütel by a slim margin. Drawing inspiration from Lennart Meri’s presidency, Ilves promised to take an active role in Estonia’s foreign relations.

At the outset, Ilves’ election provoked divided opinions. Having previously served twice as Estonia’s foreign minister, Ilves possessed strong foreign policy experience. His American upbringing and education gave him a distinct advantage in gaining the attention of the US foreign policy community. On the other hand, having spent a large portion of his life outside Estonia, others thought that he might have difficulties relating to Estonian society as a whole.

Elected for a second term in 2011, Ilves has been highly effective in increasing Estonia’s profile and status. In non-security matters, Ilves gained a significant international profile allowing him to promote Estonia as a destination for investment, to promote joint development projects in government e-services, and to advocate for improving the EU’s digital single-market.

“Ilves has been highly effective in increasing Estonia’s profile and status.”

Of even greater importance have been his achievements in security affairs. Leaving a high benchmark for future Estonian presidents, Ilves regularly spoke at events with many Western leaders. Locations for prominent speeches included some of America’s Ivy League universities and leading think-tanks on both sides of the Atlantic. Ilves’ 2016 address to the European Parliament that emphasised the importance of liberal values to solving the political and security challenges that Europe now experiences was probably his crowning international speech.

Ilves has found innovative ways to illustrate to Estonia’s key NATO allies the precise regional security challenges that the Baltic states face. As described by his national security advisor, Merle Maigre, the Estonian president first raised the concept of the “Suwałki Gap” with the German defence minister, Ursula von der Leyen.

This concept aimed to highlight a contemporary strategic difficulty for the Baltic states by drawing similarities with the “Fulda Gap”, a major security concern for West Germany during the Cold War. Suwałki is a Polish town located along the narrow sliver of land that links NATO allies Lithuania and Poland, but is bordered on each side by Russia’s Kaliningrad Oblast and Belarus, respectively.

Estonia perceives this piece of countryside as crucial for its security. NATO troops reacting to defend Estonia would have to first cross this territory without obstruction. The “Suwałki Gap”, first termed by President Ilves, has since become a key term for US leaders such as Ben Hodges, commanding general of US Army Europe and Secretary of Defence Ash Carter.

Prospects beyond 2016: possible candidates

As a small state in a challenging neighbourhood, Estonia needs a president with the profile to achieve the country’s aims – above all to maintain a hard-line EU policy stance towards Russia in light of Moscow’s actions in Ukraine and to improve NATO deterrence measures along its “Eastern flank”.

A strong president can lend important assistance to Estonia’s foreign policy, especially considering that the current government, led by the 36 year-old prime minister, Taavi Rõivas, includes many relatively inexperienced officials, and that the Estonian foreign ministry is smaller than many European counterparts.

“A strong president can lend important assistance to Estonia’s foreign policy, especially considering that the current government includes many relatively inexperienced officials.”

The current electoral system for the Estonian president dictates that the successful candidate must secure a two-thirds majority in the Riigikogu or thereafter receive a simple majority from the electoral college. The latter consists of all the Riigikogu’s members as well as certain members from Estonia’s local municipal authorities.

Each of the six parties represented in the Riigikogu have announced the candidate that they will support. The Riigikogu’s current speaker, Eiki Nestor, has been endorsed by the Social Democratic Party (centre-left); the former state chancellor of justice, Allar Jõks, has received support from both the Union of Pro Patria and Res Publica (centre-right) and the Free Party (conservative-libertarian); the former minister of education, Mailis Reps, has obtained the backing of the Centre Party; and Mart Helme will be proposed by the Conservative People’s Party (far-right).

After much deliberation, Estonia’s largest governing party, the Reform Party (liberal), was the last to announce that former prime minister and EU commissioner, Siim Kallas, will be their endorsed candidate. Having received the necessary support of 21 or more MPs, only Kallas, Jõks and Reps have enough pending support to be confirmed on the ballot for the August 29 Riigikogu vote. To reach the ballot, all the others will need the support of MPs from other parties.

While his Reform Party holds 30 votes in the Riigikogu, doubts remain as to whether Kallas can secure the further 38 that he needs from other parties to be elected successfully at the Riigikogu stage. For the past six months, the Reform Party has been spilt on the question of whether to endorse one of two candidates – Siim Kallas and the politically independent, but serving foreign minister, Marina Kaljurand.

Kallas now has the chance to be the Reform Party’s frontrunner, but Kaljurand is still not completely out of the race. In the likely scenario that Kallas does not receive the two-thirds majority to be elected president in the Riigikogu, prime minister Taavi Rõivas has hinted that his Reform Party would still have the option to nominate Kaljurand for the subsequent Electoral College stage. While Kallas has himself stated that he will remain a candidate for both the Riigikogu and electoral college stages, other Reform Party MPs supporting Kaljurand, such as Liina Kersna, have taken the view that Kallas now has the chance to “prove himself” at the Riigikogu stage and “If not, then we [Reform Party] will support Marina [Kaljurand] in the electoral college”.

Of all potential candidates, Kallas and Kaljurand possess the strongest foreign policy credentials, Jõks has instead emphasised his legal credentials, and argued that while many of Estonia’s local municipality politicians believe foreign policy to be important, “the president must do more to deal with what is going on within Estonia”.

Kallas: a competent senior statesman

Between 2004 and 2014, Kallas held three separate briefs as an EU commissioner. Before his career in Brussels, Kallas held many of Estonia’s senior government posts, including prime minister (2002-2003), minister of finance (1999-2002), and minister of foreign affairs (1995-1996). He has also been president of the Bank of Estonia (1991-1995).

For some Estonians, Kallas’ remarkable domestic political career gives him the reputation of a competent senior statesman, while his extensive experience at the EU-level has no doubt added considerable international networks and status to his CV. All these attributes would be considerable assets should Kallas be elected president. However, allegations of malpractice while Kallas was president of the Bank of Estonia during the 1990s may harm his candidacy.

“His extensive experience at the EU-level has no doubt added considerable international networks and status to his CV.”

A younger section of Estonian society might perceive Kallas as “yesterday’s man” whose approach does not portray the vibrant Western image that Estonia seeks to generate, especially in comparison with Ilves. As an Estonian émigré, the country’s communist past never overlapped with Ilves’ political career.

This cannot be said for Kallas, who forged his early political career as a member of the Communist Party, holding a number of prominent positions in Soviet Estonia before 1991. Kallas is one of the few remaining prominent politicians that assumed power during Estonia’s 1990s transition. This was when society often had to tolerate elites that had served in the Soviet administration. Against the modernising legacy set by Ilves, it is doubtful whether a Kallas presidency would have the ability to measure up to the same standards.

Kaljurand: an assuring and professional diplomat

With Urmas Paet’s nine-year spell as Estonia’s foreign minister coming to a conclusion in 2014, the ruling Reform Party initially struggled to find an experienced replacement. After a brief stint by Keit Pentus-Rosimannus, in July 2015, Rõivas nominated the politically independent Marina Kaljurand as foreign minister.

A professional diplomat, Kaljurand has previously served in multiple important foreign service positions, including as Estonia’s ambassador in Washington and to Moscow. Since becoming foreign minister, Kaljurand has been an assuring voice on international events domestically, often explaining calmly to the media the ways that the government seeks to meet Estonia’s foreign policy challenges. She has also been externally acknowledged as a constructive contributor to collective policy formation within both the EU and NATO.

“While the tone might be comparatively less striking, a Kaljurand presidency is likely to persist with many of Ilves’s foreign policy objectives.”

Kaljurand’s successful performance as foreign minister has brought her presidential credentials into focus; her name has recently topped public opinion polls. While the tone might be comparatively less striking, a Kaljurand presidency is likely to persist with many of Ilves’s foreign policy objectives. First among these will be the effort to persuade Estonia’s main allies to continue their support for NATO deterrence along its “Eastern flank”.

Estonia must show strength in uncertain times

Since its restoration of independence in 1991, both Estonia’s security and international profile have benefited significantly from having two presidents that have performed strongly at different stages in foreign affairs. In challenging times and given Estonia’s dependence on security ties within NATO and the EU, this trajectory needs to continue.

The next Estonian president must be equipped to persuade the next US presidential administration to maintain a credible NATO deterrence presence along the alliance’s Eastern flank. Should US commitment lapse under a potential Donald Trump presidency, Estonia’s leaders will have little choice but to convince its main European allies, including the UK, France and Germany, to compensate by increasing their commitment to NATO efforts.

“The next Estonian president must be equipped to persuade the next US presidential administration to maintain a credible NATO deterrence presence along the alliance’s Eastern flank.”

At a time of uncertainty in international affairs, an Estonian president that is firmly focused on foreign policy will certainly remain an unwavering asset in the effort to maintain Estonia’s national security.

I

The opinions in this article are those of the author. Cover collage by Estonian World.