Patrik Maldre describes the crucial days of 1918 when the Estonia-UK alliance was born.*

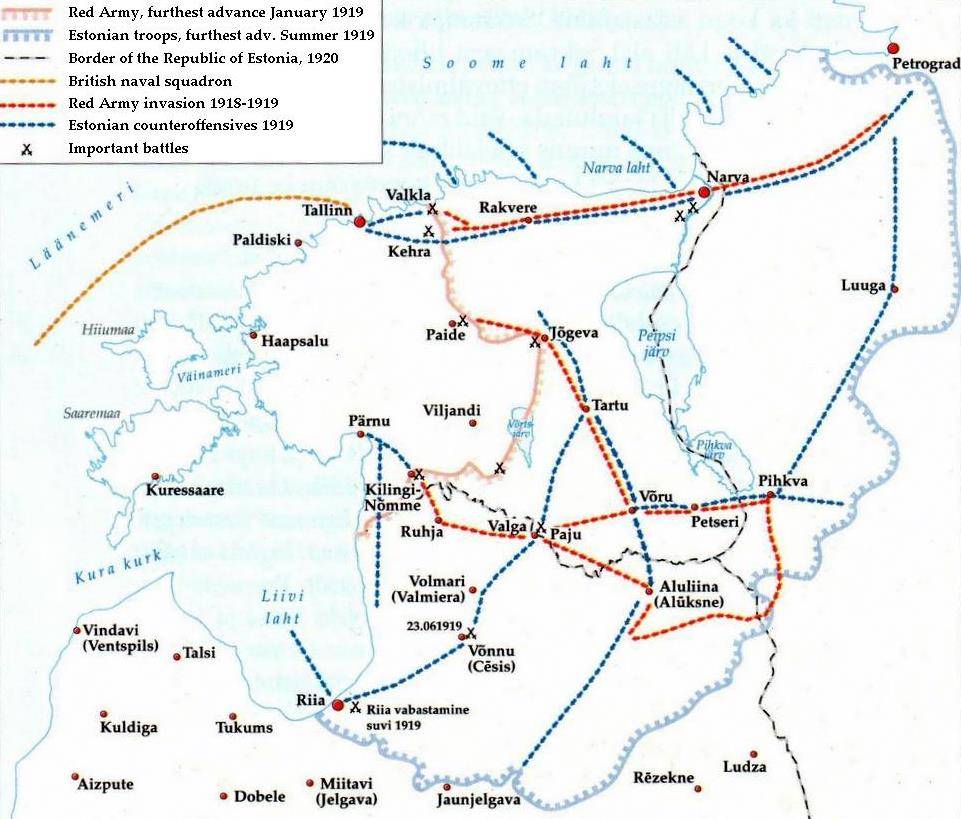

On 24 February 1919, the Republic of Estonia celebrated its first Independence Day with nearly full control of the nation’s historical homeland. And yet, only a short two months before that, the Red Army had been camped 34 kilometres (21 miles) outside of Tallinn and Estonia was on the verge of capitulation. With the weight of numbers against it, suffering from lack of modern weaponry and having no navy or air force to rely on, it may have seemed that Estonia was destined for another period of foreign rule.

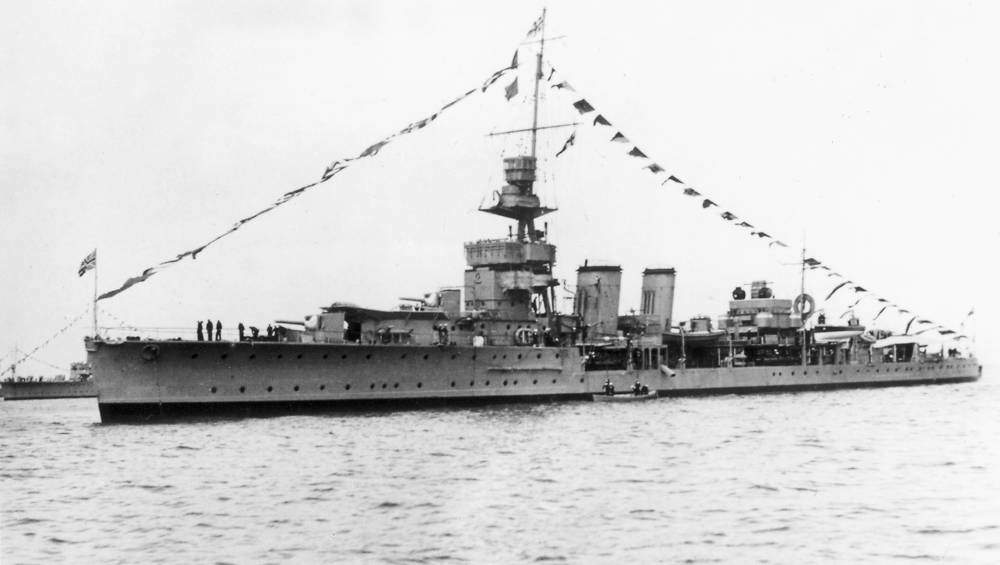

But it was not to be so. In the country’s period of need, new allies reached its shores – on 12 December 1918, a British fleet, led by Rear-Admiral Edwyn Alexander-Sinclair, arrived in Tallinn bringing guns, food, fuel and, perhaps most importantly, hope. It was in those momentous days that the modern Estonia-UK alliance was born.

British fleet played a crucial role

General Johan Laidoner, the commander of the Estonian forces in that era and perhaps the most storied Estonian war hero of all time, would later say: “I am sure that without the arrival of the British fleet to Tallinn in December 1918, the fate of our country and our people would have been very different – Estonia…would have found itself in the hands of the Bolsheviks.”

Of course, the arrival of the British in no way reduces the bravery and valour of the Estonian soldiers that successfully liberated the country and even pushed the front beyond Estonia’s modern-day borders. But it is no surprise that their morale and war fighting potential were given a significant boost by the 20 cannons, approximately 700 machine guns, 26,500 rifles, 31,000 cannon shells, 30.5 million bullets, vehicles, telephones, coal, oil, petrol and 550 tons of wheat that had arrived in Estonia from Britain by the end of February 1919.

It goes without saying that, as with any other set of foreign policy decisions, the British actions in the Baltic in 1918-1920 are better explained not by pure altruism but rather through a consideration of both its values and its interests. After a final meeting with Estonian diplomats Ants Piip, Eduard Virgo and Mihkel Martna, the British declared: “The Government of Estonia is stable, determined and based on democratic principles in its fight against Bolsheviks and disorder.”

It is significant that the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia had transformed an allied state into a hostile one, and Britain was motivated to prevent the violent spread of a communist world revolution. However, having just fought in World War I, Britain was neither able nor willing to send in ground troops to Eastern Europe. It needed local allies, and it found potential partners in Estonia and the remnants of the tsarist White Russian Army.

Additionally, Britain, being an island nation, was interested in guaranteeing freedom of the seas. Its extensive naval operations against the Soviet Baltic Fleet in this period not only guaranteed Britain future access to the Baltic but also effectively created the Estonian Navy when it handed captured Soviet vessels over to the Estonians.

Estonia the first state to repel the Soviet westward expansion

It must be stressed that the arrival of the British fleet in Tallinn alone did not win Estonia the war. The first-ever celebration of Estonia’s Independence Day on 24 February, while occurring at a triumphant moment for Estonia’s army, did not signify the end of the country’s struggle for self-determination and peace, for sovereignty and stability. A new Soviet counteroffensive was just beginning, new enemies would soon emerge in the form of the Baltic-German Landeswehr as well as the Estonian Red Army, and the White Russian forces would eventually fail to take back Petrograd and therefore the Russian state.

Yet, by the time the Tartu Peace Treaty was signed on 2 February 1920, Estonia had become the first state to repel the Soviet westward expansion and would ultimately aid Latvia in doing the same. The Estonian defence forces, which had at that point swelled to a dozen times its original size, also made exceptional use of armoured trains, among other innovative tactics.

Furthermore, the British were not the only ones to provide Estonia with assistance during the War of Independence. Nordic allies, especially the Finns, Danes and Swedes, also played a crucial and meaningful role in aiding Estonia’s achievement of self-determination; their roles are also deserving of memorialisation and appreciation.

British intervention valued

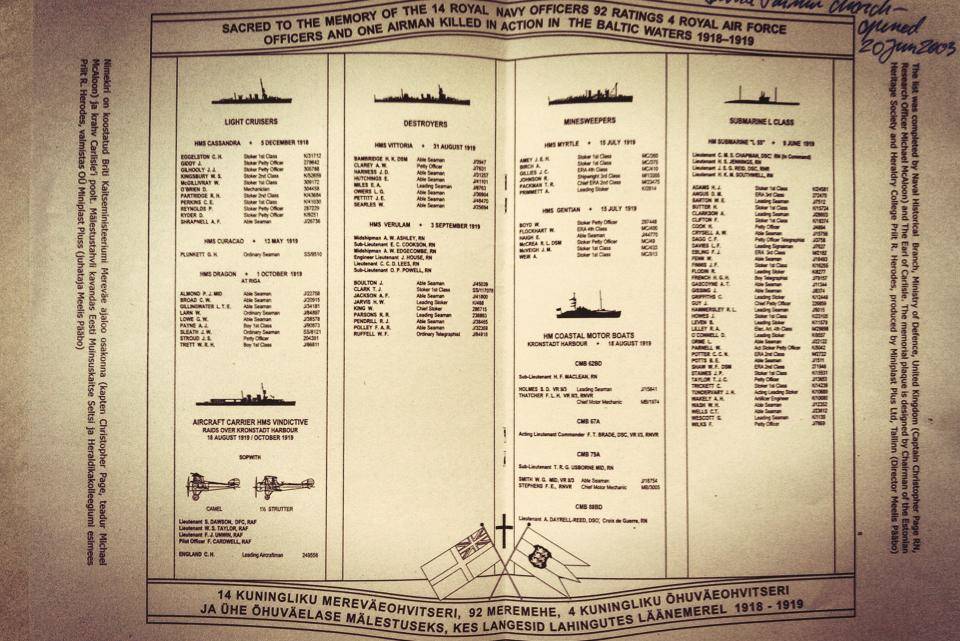

Yet the significance of the British fleet’s presence and activities cannot be underestimated. Not only did they protect Estonia’s military operations and coastal territories from being bombarded by Bolshevik ships, the overall danger of their naval mission was more than considerable.

For one, the Soviet Baltic Fleet at Kronstadt occupied perhaps the most heavily defended anchorage in the world, including with ships that had larger guns than the British vessels. Secondly, the nearest port of re-supply for UK ships was Copenhagen, and, for repairs, Portsmouth. Lastly, the Baltic Sea was the unpleasant host of over 60,000 mines. It is in this context that the British intervention must be understood and, ultimately, valued.

As we celebrate this day, the 103rd birthday of the Republic of Estonia, we should take a moment to reflect on the lives of those who contributed to our first period of self-determination.

Let us remind ourselves that the Estonian volunteers who risked their lives to drive out all would-be invaders are not the only ones worthy of remembrance. Let us reflect also on the 112 British soldiers who sacrificed their lives near foreign shores so that the Estonian nation could, for the first time in recent history, be the masters of their own land.

While this number may seem paltry next to the statistics of the fallen in the horror that was World War I, the meaningfulness of the British fleet’s actions and the political will that backed them, should never be forgotten.

In this day and age, the United Kingdom continues to be one of Estonia’s closest friends and allies. The earliest period of Estonia-UK defence cooperation is as important as how it has continued during the last decade of the Republic of Estonia’s history, and helps explain why it can and should continue to be so well into its future.

* This article was originally published on 24 February 2014.

Thanks for the article. I’ve read of the role of the British Navy in Estonia’s independence in history books but now have a better understanding of its actual role. Look forward to the rest of the series

Mrs Linda Soomre was in charge of the Tallinn City Centre Cemetery for 35 years. During the years of harshest Soviet rule she managed to preserve the integrity of the graves of 15 British servicemen who gave their lives for the cause of Estonian independence in the war of 1918-20. They were buried in the Tallinn Garrison Cemetery along with Estonian servicemen. The Soviet authorities demanded the British section of the graveyard be reused. The gravestones indeed had already been destroyed but Linda Soomre’s ingenuity, making this ground almost overnight a maintenance area for the graveyard, saved the remains of the soldiers from being violated.

In 1994 the British graves were repaired, new gravestones erected and the site was officially re-opened. For dedication and bravery in protecting the graves of British Servicemen Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II awarded Linda Soomre honorary Membership of the Order of the British Empire. On 26 June 1994 then British Ambassador in Estonia Mr Brian Low presented the Order to Mrs Soomre.

In his moving speech at Rahumäe cemetery HMA Nigel Haywood spoke in admiring of the remarkable courage of Mrs Soomre, who put her life on line for the preservation of British graves. In the darkest times of oppression she stood firm for the values that both British and Estonians share and did not allow an important part of our common history to be removed.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Defence_Forces_Cemetery_of_Tallinn

It’s rather unfortunate that the Western Allies couldn’t have been more helpful in 1940 and 1944 when the Russians moved in and enslaved Estonia.

Yes….the World was busy reading about the Nazi’s marching into Paris that day.