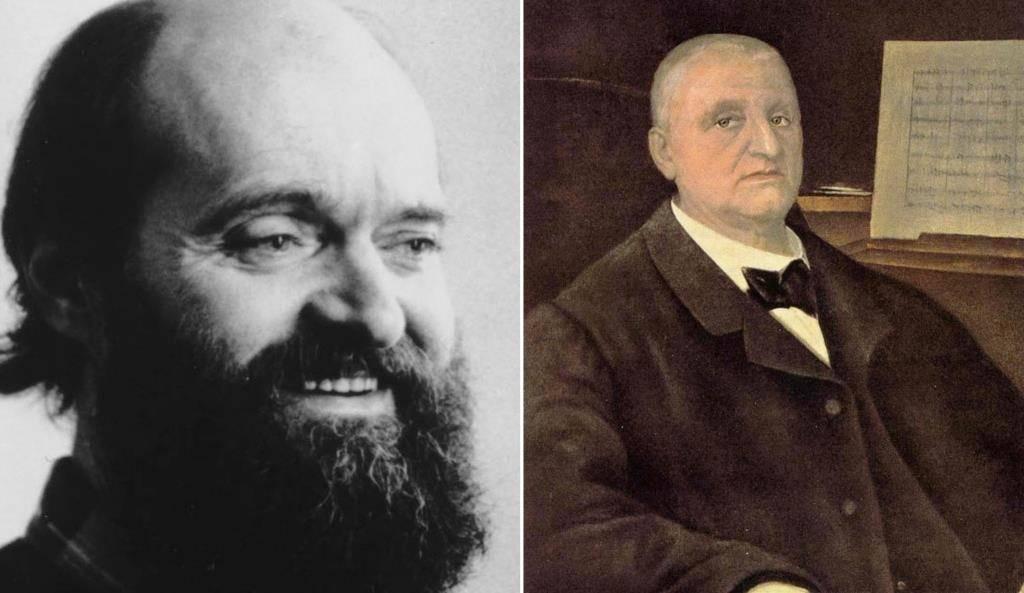

As a foremost composer of spiritually informed music, Arvo Pärt is something of an anachronism in modern Estonia. But this unique social position in which Pärt finds himself is analogous to the position of Anton Bruckner in late 19th century Austria. The following examines the parallel lives of Pärt and Bruckner and their strikingly similar relationship to their respective societies and broad musical traditions.

On a purely technical level, the music of Anton Bruckner and Arvo Pärt has rather little in common; Bruckner being one of the most prolific symphonists of the late romantic period, whilst Pärt has carved himself a unique place in music history as someone who has combined the seemingly polar styles of late 20th century minimalism with what for lack of a better word musicologists have termed ‘early music’. But beyond the technical disparities, Bruckner and Pärt share a common sense of musical pathos which is immediately apparent in their music.

A sense of semi-formal spirituality

Both Bruckner and Pärt have infused a sense of semi-formal spirituality if not religiosity into their music. Indeed, Bruckner’s epic symphonies have often been derided as ‘masses in disguise’ – a criticism that ironically has been received as a compliment by some of Bruckner’s more “devotional” devotees. Likewise, Pärt has borrowed from Gregorian and Orthodox chant, as sources of inspiration and harmonic jumping off points for his music.

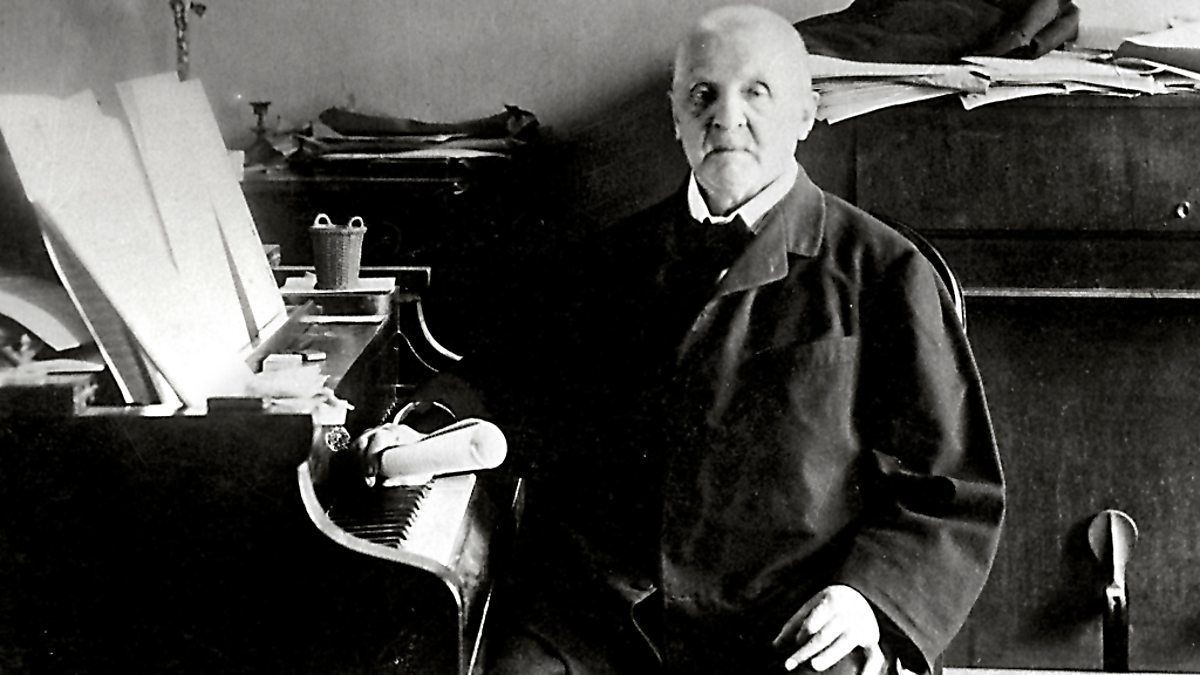

But to say that both composers share a unique parallel position in the history of music is a rather unimpressive statement. It is only when the two composers’ place in their respective cultures and societies are examined, that one can truly grasp the striking parallels between the two composers. Anton Bruckner was once described by the introspective and consciously academic Mahler as “half simpleton and half god”. In my own life, I was first struck by the many polar contradictions in Bruckner’s life, when I saw his photograph. How, I asked myself, could a man whose countenance was both insignificant and hideous, compose music that could seemingly drip from the soul of Achilles?

Whilst this contradiction may correctly appear the observation of a child, it did hint at a deeper truth. Born on the rural outskirts of Linz, Austria, Bruckner was quite literally the peasant turned humble church organist, a man for whom religiosity was essential and grand composition came with a bewitchingly humble ease. Upon his arrival in Vienna he was mocked for everything from his out of date religious lifestyle, to his shabby sense of fashion and his unassertiveness. He was a man who could have come out of the turmoil of the 17th century, yet was living in a prosperous, increasingly secular, intellectually driven late 19th century Vienna.

And yet these early obstacles did not ultimately retard his success. In spite of a personality and lifestyle which was out of tune with the zeitgeist, he found a friend and supporter in the form of Richard Wagner, a man who helped define the musical and indeed philosophical and political zeitgeist. Along with Wagner, Bruckner’s unusually high insecurity and self-doubt which caused him to revise his pieces regularly, was aided through the support and companionship of some of Vienna’s most prolific musicians including the likes of Arthur Nikisch, Josef Schalk, Hermann Levi and later Ferdinand Löwe.

As Wagner was writing about German unity and amalgamation and Richard Strauss was exploring music’s resonance with the futuristic philosophy of Nietzsche; Bruckner was content to represent a fusion of older styles with a contemporary voice. Bruckner’s symphonies essentially combined a modernised harmonic structure reminiscent of Bach and other Baroque composers with the traditional sonata form of Beethoven. But within this framework Bruckner employed the modern behemoth Wagnerian orchestra and infused into his pieces a lyrical drama that was far more similar to the narrative drama of Wagner than many tend to realise.

A synthesis of older styles with a highly contemporary sonic pallet

Like Bruckner, Pärt’s music represents a synthesis of older styles with a highly contemporary sonic pallet. Pärt’s explorations of pre-Baroque music combined with his use of modern instrumentation often in a minimalist style, represents an important analogue to Bruckner synthesis of earlier styles with those of his own time. Perhaps more importantly though, Pärt’s spiritual inclination in a highly secular age and in particular a highly secular culture is rather analogous to Bruckner’s position in his own time and place.

Indeed, modern Estonian culture is one that has happily eschewed the rigid dogmas of both communism and religion to a greater degree than any other country in Europe. Estonia is in many ways a model of a healthy post-Enlightenment culture, one which has embraced scientific advancement, a logical approach to governance and a national life devoid of ideologies which uproot the sovereignty of human freedom.

And yet for Arvo Pärt, unlike most educated people in the world – and especially unlike the vast majority of Estonians, religion is not a strange relic of the past, but a force of deep emotional attraction. Pärt’s spiritual approach is rather different than Bruckner’s in some ways. Bruckner was a staunch Catholic dogmatist, even though ironically 20th century Catholic reactionaries found his music too romantic for a liturgical setting; the irony is biting and hypocritical indeed!

By contrast, Pärt’s religiosity represents a kind of post-Second World War syncretism, a desire to create some sort of understanding from a myriad of vague sources. Because of this, Pärt has plundered a variety of musical traditions from a number of liturgical sources, whereas Bruckner’s sense of sacred music was placed firmly within a central-European Roman Catholic tradition.

Shared pathos

But what of the broader response to the music in late 19th century Austria and late 20th and early 21st century Estonia?

In spite of Bruckner’s initial missteps in Vienna, the patronage of Wagner helped elevate Bruckner’s symphonies into the realm of mainstream popularity across the Germanic world.

This success continued after Bruckner’s death in the 20th century. The National Socialist Government of Germany promoted Bruckner’s music heavily, and indeed it was the second movement of Bruckner’s 7th symphony which was played on the radio upon the official announcement of Hitler’s death. Because Bruckner’s own ancient, simpleton values were so anathema to those of the Hitler Reich, Bruckner’s reputation did not suffer after the Second World War – and thanks to the wider proliferation of central European conductors in Western Europe, the USSR and America; Bruckner experienced something which approached popularity outside the Germanic world for the first time in earnest after the Second World War.

Likewise in spite of early difficulties and protracted conflicts with the Soviet authorities, Pärt has become nothing less than the most widely loved Estonian artist in the world, producing a music, the passion, and beauty of which transcends any potential ideological divides. It is a very fair statement that Pärt is the most widely listened living composer in the world; someone whose music has achieved what Nietzsche referred to as a cosmopolitan appeal, in respect of the universality of Beethoven’s continued popularity during a late 19th century when music and nationalism became increasingly bound up.

Thus we have two parallel lives. Two composers who shared a pathos, who shared a lack of concern for the trends and habits of their era, and two composers who achieved popularity at home and abroad in spite of this.

I

Cover: Arvo Pärt and Anton Bruckner. The images are courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.