Estonian biologists have created an app to shine light on one of the most threatening issues on this planet – biodiversity loss.

This article is published in collaboration with Research in Estonia.

“If I would go back to the exact same forest that I visited in the 80s, I would now hear 25 per cent less birds singing than back then,” Aveliina Helm, one of the best-known Estonian biologists and a senior research fellow at the University of Tartu, says.

Every year, there are around 100,000 breeding pairs of birds less in Estonia than in previous years. Approximately half of Estonia’s territory is covered with forests, which sounds great. But in fact, only around one-two per cent of it can be considered truly natural old-growth forests – the rest is young and managed.

Within only 70 years, almost all the grasslands (95 per cent) have disappeared and flowers like globeflower and bird’s-eye primrose have gone with them. Even cowslip is becoming increasingly rare. And these are a few examples out of thousands.

Our forests, parks and grasslands are becoming quiet and disappearing. Why does it matter?

Replacing grasslands, wetlands or old-growth forests with monotonous agricultural fields, young production forests or just cities and settlements is the main driver of biodiversity loss worldwide.

Besides it simply being sad, we don’t really know what it would do to the planet if we wiped off most of the species, Helm says. Our clean water and air depend on the biodiversity.

We depend on insects, birds, plants and animals more than we realise. Will we have enough fertile soil, clean water and clean air without them? Will apple hearts or leaves falling from trees decay in nature and turn into soil in the future? Will vegetables and fruit still grow?

“A big part of the ecosystem functions underground, in the invisible world,” Helm notes. “If we keep hammering on this very complex and delicate engine, it’s not going to end well.”

In short, we should be just as worried about biodiversity loss as we should be about climate change.

Amid many crises and problems humanity is facing these days, it is difficult to talk about something as invisible and as difficult to grasp as this disaster in slow motion. That is why Helm and her colleague decided to visualise it. And instead of only speaking of doom and gloom, they turned it around and gave simple advice on how each person can make a difference.

A simple way to show a complex issue

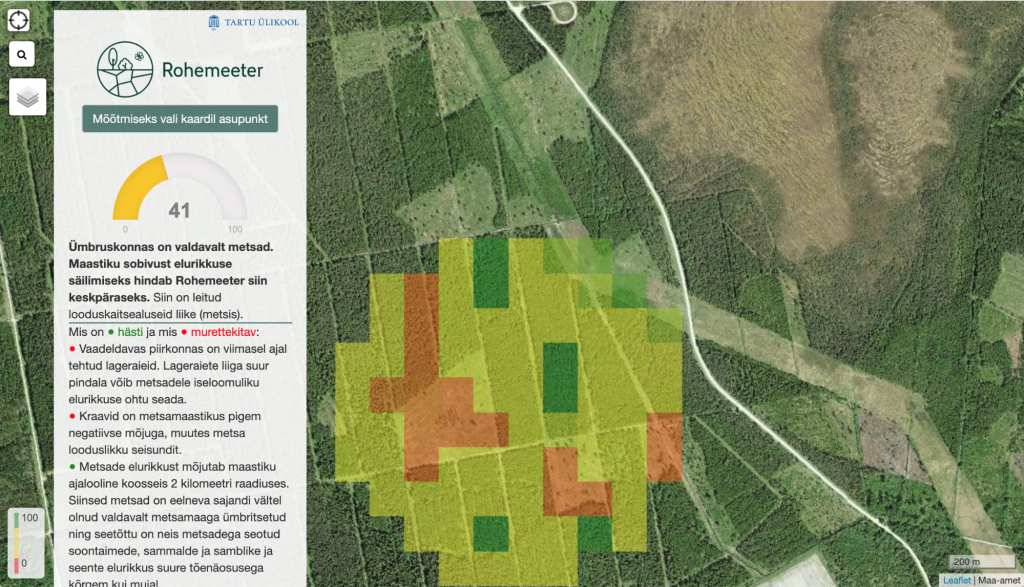

Click anywhere on the Rohemeeter (“Greenmeter” in English) map and it will tell you how diverse the specific spot is out of 100. For instance, let us click on Kadriorg park in Estonia’s capital, Tallinn. At the heart of it lies the president Kersti Kaljulaid’s office, surrounded by museums, playgrounds, forests and a residential area.

The map displays us the number 66. The description says it is not an ideal landscape, because of too many hard-coated surfaces and because some patches of land are only covered with lawn. But it is not too bad either, because of private gardens, protected areas and bodies of water. The map’s advice for this specific location is to diversify the plants and mix it up. Parts of the gardens could be made into flower beds, and the lawn could be left to grow in other parts.

Aveliina Helm created the interactive map together with her colleague at Tartu University, Meelis Pärtel. They used 70 different maps, including historical ones, to draw a full picture of what is really happening in Estonia in terms of biodiversity. It was launched in April 2020.

If climate change seems difficult to tackle for a single human being, then biodiversity loss is something very local. Anyone can get their fingers muddy and do their part. Grow flowers or tomatoes on the balcony, replace a rocky patch of land with flowers and grass. These urban gardens on balconies, terraces, roofs and yards are actually nature’s hotspots in cities, Helm says. These are great places for biodiversity and luckily, it is becoming increasingly popular to do urban farming.

“Everyone’s nature conservation,” as Helm calls it. And it is a noble thing to do, because little creature’s lives depend on these little natural patches.

There is no one solution

The idea of being a nature loving nation has fooled Estonians into believing that the country’s flora and fauna is protected. Like in most places around the world, this is a myth. Just another myth that Helm is trying to bust.

Take planting trees, for instance.

A study from last summer revealed that planting trees is by far the best climate change solution. It concluded that increasing forest areas is overwhelmingly the most (cost) effective way to draw carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. No other technological or scientific proposal comes even close to it. Many organisations all over the world mobilised and started planting. Even the US president, Donald Trump, spoke about planting a trillion trees.

It seemed the problem was finally solved. Let us take down trees and keep planting new ones!

But according to Helm, things are not as simple. Simply by planting new trees just anywhere endangers many species that can only survive in grasslands, bogs or old wild forests.

For instance, white-backed woodpeckers prefer forests with a high percentage of dead trees and fallen timber. Butterflies and ladybugs live in grasslands. They cannot survive in forests or large crop fields.

“We are playing god on this planet. But do we have the right to do that?” Helm asks.

Biodiversity loss is silently destroying our planet, but it is not a lost cause if we still care. The Estonian scientists’ interactive map is one example of how to make complex and incomprehensible topics more visual and why not even fun.

Helm’s advice for beginner nature conservationists:

- Be lazier! Do not overly organise your surroundings. Not everything has to be covered with asphalt, not all the lawn has to be mowed. Some trees can stay fallen, some bushes and hay can stay around. Use a scythe rather than lawn mower. It’s quieter, too, and counts as exercise.

- Grow your own food on your balcony, garden, kitchen or even on the roof.

- Learn to recognise different species. Do not be fooled by the green colour. If there are only two-three different species represented, it is still a very poor landscape.

- Big crop fields are one of the most harmful landscapes. To make them more diverse, create smaller fields with patches of more diverse landscapes in between. Those patches could have longer grass and bushes. Ladybugs and spiders that help pollinate the crop or eat pests do not live on the crop field, but nearby. For instance, ladybugs eat greenflies, but they only enter the fields for 200 metres from the edge of the field. Spiders also go 200-300 metres into the fields.

Cover: Aveliina Helm. Photo by Andres Tennus.