The smoke sauna tradition in Estonia’s Võromaa region is listed by UNESCO as a representative of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity; Adam Rang shares his experience from one of the smoke saunas.

The first thing we notice is how easy it is to breathe. Anni – my wife – and I are crouched inside a smoke sauna while it’s being prepared for us in the Võrumaa region of Estonia. Beside us is a crackling wood-fire under a pile of large stones, from which white smoke is spewing upwards.

A smoke sauna has no chimney, so the smoke hangs in the air above us, ending abruptly just above the top bench.

There’s enough space to lie down there, if needed, below the smoke where the warm air has a rich aroma but is surprisingly clear. The smoke is white because it is burning as a full fire with plenty of oxygen, while the door is kept open during heating to enable fresh air to flow in and smoke to drift out.

“We are not heating the sauna,” Eda Veeroja, who is crouched down with us, says. “We are heating the stones.”

After six to eight hours of heating, the fire will be left to die out; then the last of the smoke will be ventilated. The air will be completely clear to the ceiling once it is time to enter later for bathing.

The stones, however, act like ancient batteries. They’ve been absorbing and storing the heat energy from the fire all day so that they will continue to radiate heat for us long into the night.

The sauna tradition, as most people around the world know it today, originated in this way among Finno-Ugric peoples living here around the Baltic Sea region. Other cultures have their own sweat bathing traditions, similarly based around heating stones in other ways.

After thousands of years of smoke saunas, chimneys were introduced towards the end of the 19th century and became more common in saunas across Estonia by the 1920s. And since the restoration of Estonian independence in 1991, electric saunas have overtaken them in popularity, too.

But comparing many of those saunas with a smoke sauna is like comparing fast food with fine dining (in fact, Burger King in Helsinki does indeed have its own sauna of dubious quality).

While wood-fired and electric stoves have made major advancements in recent years to bring back the emphasis on heated stones, the smoke sauna remains the most revered of all saunas – and new ones are still being built today.

And Eda’s smoke sauna is the most revered of them all here in Estonia. It’s located at Mooska farm, which she runs with her partner, Urmas. Together, Eda and Urmas are among the most influential guardians of the local Võro culture.

In recent years, their smoke sauna has managed to reach the front covers of both the New York Times magazine and the Boston Globe magazine – both of which wrote glowing reports on Estonia and its rich smoke sauna heritage.

Eda remains humble – although she smiles, remembering the controversy caused by one of those covers, which alarmed some of its more conservative readers. This is somewhat ironic, considering it depicted traditional values being conserved.

In 2014, following a five-year application process, Eda and Urmas successfully convinced UNESCO to inscribe the Võro smoke sauna tradition into its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. The list is kept by the UN body to demonstrate the diversity of human heritage and raise awareness of the importance of preserving it.

There’s a common misunderstanding about this, though. Journalists often write that it’s the smoke saunas that are listed. In fact, it’s the smoke sauna tradition. That distinction is important because the sauna is not just a hot room or a building. Here, it’s a way of life.

As explained by UNESCO, “the smoke sauna tradition is an important part of everyday life in the Võro community of Estonia. It comprises a rich set of traditions including the actual bathing customs, the skills of making bath whisks, building and repairing saunas, and smoking meat in the sauna.”

All human life is here

“Everything in the sauna has both a practical and a spiritual purpose,” Eda says.

That’s not quite the impression you would get from visiting an average gym sauna today. Yet, throughout history, the sauna has always been a multi-functional space – serving the needs of humans to survive and thrive in this sometimes-challenging landscape, and ultimately understand who they are.

Remember that space on the top bench beneath the smoke? There is indeed a good reason why it might be needed, even during the heating process.

That is the traditional place of birth and healing for Estonians since long before hospitals were available. The sauna could be lightly heated at the same time to provide some comfort.

And the sauna is not just for humans. Animals, such as chickens, would shelter inside here too – just not when it’s being used for bathing. And, after their life, they would be cooked and smoked there too.

This is the main produce of Mooska farm. Their sauna-smoked meat is sold at markets across Estonia, although the occasional car would pull up during our visit to buy it directly from them, too.

Unsurprisingly, Estonia’s modern commercial food hygiene rules are a little less enthusiastic about preparing food in the same space where people bathe. There is a loophole, though. Here, and at other commercial providers, a separate sauna has been built just for smoking meat.

Pork is most commonly smoked in the sauna, but lamb, poultry and venison are also prepared there in the Võru region.

The smoking process is complex and infused with old traditions. It’s a skill that’s passed down through generations.

The meat is soaked in salty water for at least a week, then placed in the sauna either on special shelves or hooks from the ceiling, first with the rind facing the floor.

The smoking process lasts two to three days. During that time, the fire is kept alive and the meat is periodically turned in order to get just the right exposure to both heat and smoke simultaneously.

Historically, families across Võromaa would commonly smoke their own meat on their home farms. Over the past few decades though, the proportion of homes here with their own animals has declined sharply. Sauna-smoked meat is still widely enjoyed, but the skill of preparing is now left to the wisest members of the Võro community – like Eda and Urmas.

Welcome to Võrumaa / Võromaa

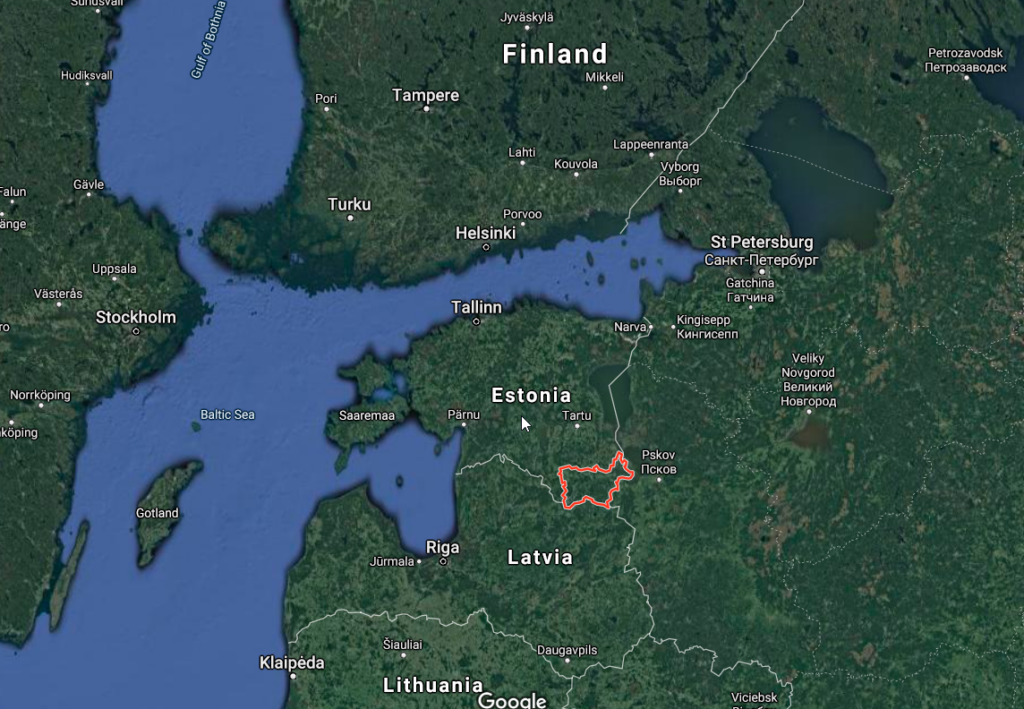

Võrumaa is Estonia’s most south-easterly region, sharing a border with both Russia and Latvia. It’s people and culture once spread further towards the centre of Estonia, an area now simply known as Vana-Võromaa or old Võrumaa.

Võromaa is Võrumaa in the local language, Võru. That difference may be subtle, but much of Võru is difficult for most Estonian speakers to understand. There is no clear way to distinguish between a regional dialect and a separate language, but Võro could be described as both.

Smoke sauna, for example, is suitsusaun in Estonian but savvusann in Võro – which is actually closer to Finnish.

When I talk to people abroad, they are sometimes surprised to learn that Estonians have their own language – despite being a country of just 1.3 million people occupied by various neighbours throughout their history. The fact that there are still widely spoken regional minority languages, too, is even more incredible. In fact, even Võrumaa has another minority language of its own – Seto.

Had history worked out differently, the Võro and the Seto people may have had their own states. But they remain nations within a nation, freely and proudly coexisting in their multiple identities.

For Eda, understanding your roots is what matters most in the sauna.

A sauna state of mind

But first, we are sent to the forest.

According to Eda, preparing ourselves for the sauna is based on communication with nature, the cosmos around us, and our ancestors. These themes are deeply intertwined into Finno-Ugric languages and influence how their speakers see the world.

Anni mentions that she’s feeling slightly uneasy, as the night is our first away from our one-year-old son since he was born.

“You need a clear mind to enter the sauna,” Eda explains. “We must first relive ourselves from everyday troubles, thoughts, anger and rush.”

So, she summons a guide who knows the local trails better than anyone – her dog, Ella.

Mooska talu is located beneath the highest hill in the Baltic states, Suur Munamägi. The Baltics are, however, about as flat as a pancake. So, reaching the summit was a slightly less than gruelling five-minute walk up an already elevated gentle slope to a height of 318 metres (1,043 ft).

Opposite the hill, Ella takes us into Haanja Landscape Conservation Area – a dark sprawling wilderness of spruce trees and bogs that are considered sacred.

Buildings made from wood felled here are said to spontaneously catch fire, a convenient curse for warding off wood cutters. The only felling has been carried out by beetles that live in the trees, of which there are more than 80 species here. Their activity eventually brings down the trees they inhabit, making a new contribution to the rich ecosystem here as the logs are slowly reabsorbed into the ground over several decades.

In the heart of this forest, we found Vällamägi, a double peaked hill said to be inhabited by a witch. At 82 metres (269 ft) from base to peak, this is the highest climb in Estonia.

From there, we return with Ella, relaxed and ready to bathe in the smoke sauna.

Into the smoke sauna

We begin in what Estonians would call the eesruum, which literally means pre-room. In Võro, it is known quite differently as vüürüs.

This is where we not just get undressed but will also return many times during the sauna for socialising, drinking tea (or something stronger), and even sleeping. There’s a roaring wood fire in the centre.

Wearing nothing but felt hats, we then make our way next door to enter the hot room. Estonians call this the leiliruum, although Võro – like Finnish – makes no distinction from their name for the sauna.

“Tere, tere sannakõnõ,” says Eda to greet the sauna as we step inside what is considered a holy place. She then proceeds to greet different elements of the sauna separately, such as the stones and the steam, all of which are considered sacred.

The sauna experience here is split into three parts.

The first steams are for cleansing.

The rituals focus on clearing our minds and mentally rooting ourselves into the earth below us and connecting with our ancestors before us. Historically, a normal temperature in a smoke sauna is around 65°C (149°F), which is quite mild by the standards of modern saunas. Today though, the temperature is around 85°C (185°F), because the sauna is already hot from the previous four days of saunering here.

Amid the pandemic, oversees visitors are rare – but they are just as busy because Estonians are taking more holidays within their country, seeking out authentic experiences such as this. The sauna is booked up until next year.

The humidity is raised considerably when water is thrown to the stones, making the temperature feel considerably higher. This sauna steam is known as leil in Estonian and lõunõ in Võru. In both cases, as with every other Finno-Ugric language, the word for sauna steam originates from an older word that means breath or spirit, essentially the very essence of what it means to be alive.

The air has a rich smoky aroma and is much more comfortable and soothing than an average gym sauna at the same temperature.

Ventilation is considerably better, for a start. There’s also a special feeling when heat and steam arises directly from large stones such as these with no other power source running in the background.

We know it is time to leave the room when we can imagine no greater feeling in the world than jumping into the cool lake outside, which we occasionally do so.

While outside, Eda describes how traditionally you wouldn’t say no if someone arrives seeking a sauna. This was important in older times – long before the invention of Airbnb – when people would travel around and be able to find a place to wash, warm up and rest for the night inside the sauna.

As if on cue, a neighbouring family arrives out of the darkness, clutching towels and are invited into the sauna with us.

The second part of the sauna experience focuses on our reason for being there and is tailored for the occasion.

It’s Saturday, the traditional sauna day, and so would ordinarily focus on washing. However, we could also use this time to reflect on creativity, healing, remembrance, protection, relationships or a wide variety of other purposes. No two sauna experiences are the same, Eda says.

We rub ourselves from bottom to top with grounded plants and salt, which is believed to provide protection. Anni and I then both choose our whisks – the bundles of branches that we step back inside to beat ourselves with. Everything has a ritual to it, connected with ancient beliefs passed down from parents to their children. We beat ourselves from the feat upwards, men starting with the right foot and women with the left foot.

After that, we both receive a massage with honey and the whisks, placing us into a deep dream-like state. We return to the vüürüs and are wrapped in blankets. Some time later, we awaken, drink more tea and return for the final steams.

This closing part of the sauna experience is focused on gratitude.

The rituals continue as we breathe the steam through mint leaves then rub our bodies clean one last time with them.

“Tennä väega,” says Eda to the sauna as she departs the room for the last time tonight. This form of thanks is difficult to translate, based as it is on the uniquely Finno-Ugric way of seeing the world around us. It is a thanks using all the energy of the universe. We do the same and depart to wash and dress.

Washing is just as important a part of the sauna experience. There is soot across our body, and it is so fine that it buries deep into the skin and takes a long time to get off. So, it’s easy to tell whether someone has washed themselves thoroughly after a smoke sauna.

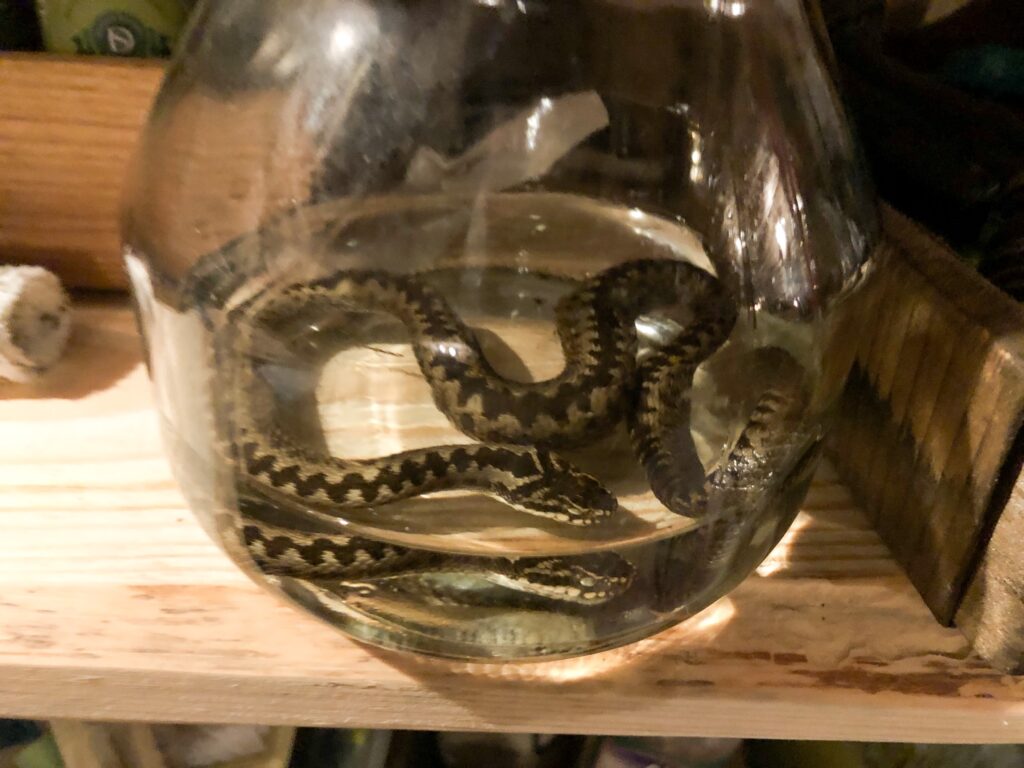

There is one last surprise waiting for us in the vüürüs.

Eda brings down a jar from the shelf and opens it.

Inside is a snake submerged in a clear liquid. This is a local moonshine, used for rubbing on as a medicine but also as a drink. The snake, a viper, is submerged in grain alcohol for around six months by which time its venom forms part of the drink. It is no longer possible to make this drink as vipers have been added to the protection list, but this one has been on the shelf for a long time.

We take a sip. It tastes exactly as you might imagine.

After a sauna, it is traditional for the family to dress in clean clothing and sit down for a meal together. I’m delighted that it contains sauna-smoked meat. It tastes smoky, fatty, full of flavour and so, so good.

“Jätku leiba,” we say in Estonian. It means “always have [black] bread” and is the more traditional way of saying bon appetite. After all, you will always have an appetite. You may not always have the luxury of bread, as Estonians know too well, historically.

We chat about the complexities of heating smoke saunas.

Many smoke saunas have an unfortunate tendency to burn down, whether due to poor construction, poor maintenance or poor knowledge of the processes taking place within the room.

The soot, which builds up on the walls and stones, can act like gunpowder in an under-cleaned and overheated sauna. Added to this risk is the fact that the stones move around as they expand and contract through temperature changes, which creates new channels through which this gunpowder could alight and blast out.

Eda and Urmas grew up with this kind of knowledge. It’s in their blood. And they want it to live on for future generations to enjoy the smoke sauna tradition.

Around the table, we also laugh with Eda about her experiences hosting different international visitors, particularly the media crews. It tends to be quite the cultural shock. They even had an entire group of Korean celebrities here, including a much-loved K-Pop star who still occasionally chats with Eda on Facebook – presumably much to the envy of several million fans.

“Sometimes, the producers begin by telling me exactly what they want to film,” Eda sighs. “But they do not know our sauna culture so how can they know what to film? As a rule here, we are in charge of what happens.”

For them, what matters most is letting more people around the world learn about their sauna tradition and who they are as a people.

“What have you enjoyed learning here?” Eda asks after dinner.

“Well,” I reply. “I’ve learned how much I still have to learn.”

“Me too,” says Eda. “We are all always learning.”

This is a lightly edited version of the article originally published by Adam Rang in Medium. You can follow Adam’s take on Estonian sauna culture also on Instagram, Facebook or Twitter.

Cover: Mooska farm’s smoke sauna. Picture by Adam Rang.

I spend many month in Estonia and had many delicious meals over my time, but I was unaware of sauna-smoked meat! I am sure I would have loved it. Surely what I will try on my next vacation there.