Europeans throw most of their wool away before using it, a fact that has baffled Estonian textile designer Katrin Kabun for decades. Here’s her solution.

Online shopping is booming and goods are being shipped around the world. The need to protect those precious products is growing too. Most of the orders are packed in bubble wrap, but just imagine the amount of plastic that millions of online consumers produce every year.

Luckily, there is a more sustainable alternative. The sheep have already figured it out for us. Scientists around the world are inventing new materials, but these furry creatures already make the ultimate high-tech material, and in massive quantities. Globally, two million tons of wool is created every year.

Wool can repel bacteria, improve air quality, isolate sound and act as a fire retardant. It retains temperature, even when wet. And the cherry on the cake? The wool is, of course, completely biodegradable. No other artificial material comes close to such a performance. This miracle material is made of animal protein fibers consisting of 60 per cent simple proteins, 15 per cent humidity, 10 per cent oil, 10 per cent sweat and 5 per cent of other plant-based additives.

Katrin Kabun, a researcher and lecturer at the Estonian Academy of Arts, explains what wool not only consists of but can also do for society in her recently published book, “Archaically High-Tech”. She wrote it to describe wool as a material through the eyes of a scientist, and is a testament to her wider concern regarding the faith of wool.

Most European wool gets thrown away, buried in the ground or burnt. “How could it be?” Kabun has wondered for many years. “I was knitting women’s clothing in the 90s to make a living,” she explains. “To my surprise, I couldn’t find natural Estonian yarn, most of it was imported from elsewhere, many of it artificially-made.” At the same time sheep were producing so much wool that nobody seemed to need.

Pop culture pushed the wool out

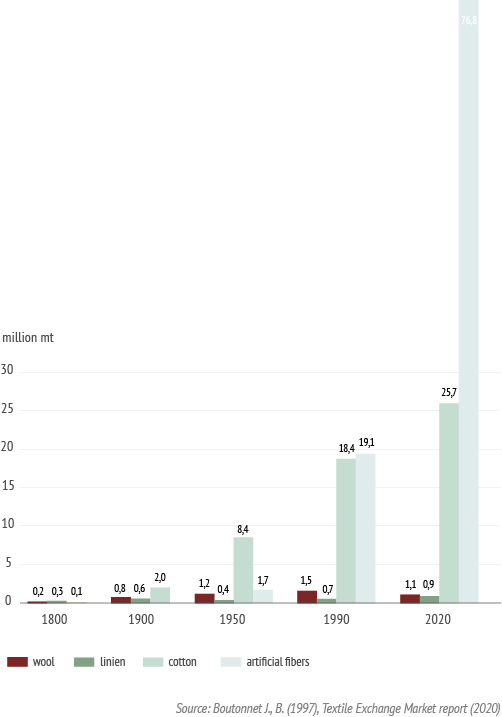

In the middle of the last century, scientists started experimenting with artificial and synthetic fibers to create new materials, Kabun explains in her book. Women started buying elastic and sleek nylon stockings instead of those made from wool and linen. Crimplene dresses came into fashion. As wool was shoved to the back of the wardrobe, sheep farmers resorted to raising their herds mainly for meat.

Once a source of clothing, pruning now became a laborious obligation that had to be done at least once a year. Suddenly the quality of the wool didn’t matter anymore. It wasn’t economically sensible for small sheep farmers to wash and make use of the wool. So, out of sight the fluff was thrown.

As Kabun further studied the properties and the uniqueness of wool, nobody else seemed to be bothered by the disappearance of it. “I even started doubting myself”, she says, but quietly continued her research at Estonia’s art university.

In 2019, she poured her worries out to a journalist, who published an article about the phenomenon in an Estonian newspaper, Eesti Päevaleht.

Anna-Liisa Palatu owned an online store at the time and was looking for a sustainable material to package orders. She happened to read the article and something “clicked”, as she recalls. “Wool seemed like the perfect solution – free from fossil fuels, in excess and naturally elastic,” Palatu explained.

She quickly wrote to Kabun and in a few months, a new company was born. Estonia’s biggest logistics operator Omniva quickly jumped on board. They now sell envelopes made of wool.

Their startup, Woola, is now creating “bubble wool”, wool envelopes and bottle sleeves.

Having been in business for less than two years, Woola has raised more than three million euros from investors in the United States and Estonia. The company is expanding to the UK, France and Germany.

The founders of the company believe all European e-shopping goods could be wrapped in wool. The sheep have plenty of it to share.

Estonian wool’s comeback

Of all the regions in the world, Estonia is the perfect place to rediscover wool. The culture in this small Baltic nation is inextricably linked to wool-based handicrafts like knitting and felting. All Estonian children can choose to learn knitting at school.

Western European hobbyists regularly come to Estonia to learn about the unique patterns and knitting techniques. Estonia’s wool is well-known in those circles.

Only recently an Estonian Native Sheep breed was officially registered, showing how closely Estonians and sheep have inhabited this land for thousands of years. “Now we can say sheep have officially been part of our culture,” says Kabun, who took part in collecting DNA samples from Estonian sheep. “We have the obligation to protect them!”

Only by looking at different shades of gray throughout natural Estonian wool, a wide pallet of colours appears.

Still, even now, most of the wool Estonians are knitting with is imported from abroad, as local wool goes to waste.

The quality and the size of wool’s fibers varies. Some may feel cuddly while others can be uncomfortable against the skin. Not all wool is suitable for modern clothing, but bubble wool doesn’t have to be thin nor does it have to feel soft. Kabun and her team found a way to mix different types of wool and bind them together. The length of the fibers doesn’t matter for a lipstick or a ceramic bowl shipped across the world. Its job is to keep the wrapped item safe.

Woola uses wool from different small farms all over the country.

In Kabun’s view, things are slowly improving for wool. She believes “the wool problem” will be solved in 10 years. “Sustainable economy lies in the economy, environment as well as the community,” Kabun, who is not against plastics that are useful in certain fields like medicine, notes. “We just need to find a balance between these three pillars,” she adds.

If Kabun’s predictions do become a reality, then wool could once again rise from the ashes and sheep will finally get the credit they deserve from all their hard work.