Decades of work and collaboration led to a green energy storage solution – Estonian researchers Jaan Leis, Mati Arulepp and Anti Perkson found a way to use curved graphene to store energy and emit it quickly; their invention ultimately led to a company called Skeleton that will soon open the largest supercapacitor factory in Europe.

This article is published in collaboration with Research in Estonia.

Essential metals are running out, and with them our choices to commute with cars, using phones or typing away on our laptops. Scientists have looked for alternatives and suggested for decades that graphene could provide a potential solution for energy storage.

Most often, however, it’s only been a theory.

Three Estonian inventors put the theory into practice – and it worked. It brought them one of Europe’s most prestigious innovation prizes – the European Inventor Award – this summer.

Graphene is a wonderful material. As a form of carbon, it can be found everywhere. It’s easy to make. It’s not toxic. The tip of your pencil is made of graphene. The biggest plus? It conducts electricity well at room temperature.

Jaan Leis, Mati Arulepp and Anti Perkson found a way to use curved graphene to store energy and emit it quickly.

They use it in supercapacitors, which are like batteries, but the energy is stored in smaller quantities and can be charged in seconds rather than minutes or hours. They are best for short intense bursts of energy, which is very beneficial if you need to start a car or a train, or even a ship engine. Supercapacitors are essential for producing and storing green energy.

The curved graphene invented by Leis, Arulepp and Perkson made the existing supercapacitors much more efficient. They could keep and provide bursts of energy better than other commercial carbons, withstanding over one million charge cycles. They are up to thirty per cent more efficient than other analogous supercaps.

Their curved graphene is now flying in space, moving in trains and cars worldwide.

Helping start cars in winter

The three friends started together in a private research institute, inventing and improving technology. “We were young men, all running sprints back then!” Perkson said with a smile.

They dared to dream and had the courage to experiment. They had already started synthesising curved graphene back in 1998. The material they invented had been theorised on paper some 25 years earlier. “We always wanted to innovate and improve technologies, so we started from zero and took the existing theories apart,” Arulepp said. “We just wanted to bring ideas to life.”

They built the supercapacitor and soon the rumours about it started spreading throughout Tartu.

During freezing Estonian winters, if someone couldn’t start their car, they would knock on their lab’s window. They knew the guys had something helpful there. Their supercapacitor module could start the car in seconds and worked like a charm!

From small metal box to Skeleton

This small metal box they worked on would turn out to be the beginning of a company called Skeleton.

Skeleton is now building Europe’s largest factory for supercapacitors. Its customers vary from Škoda to the European Space Agency, and to date the company has received over €200 million in investments.

The company was founded by young students with a good business sense, Taavi Madiberk and his coursemate Oliver Ahlberg. Madiberk had spent his summers watching Leis, Arulepp and Perkson work. His father Vello Madiberk was also their close colleague.

It was around the time when Estonians founded and developed the communications platform Skype – and Madiberk was inspired. “Skype changed the entire ecosystem in Estonia,” he recalls. “We need more examples of success.” He was impressed by the new material his father’s friends were working on and decided to take the leap.

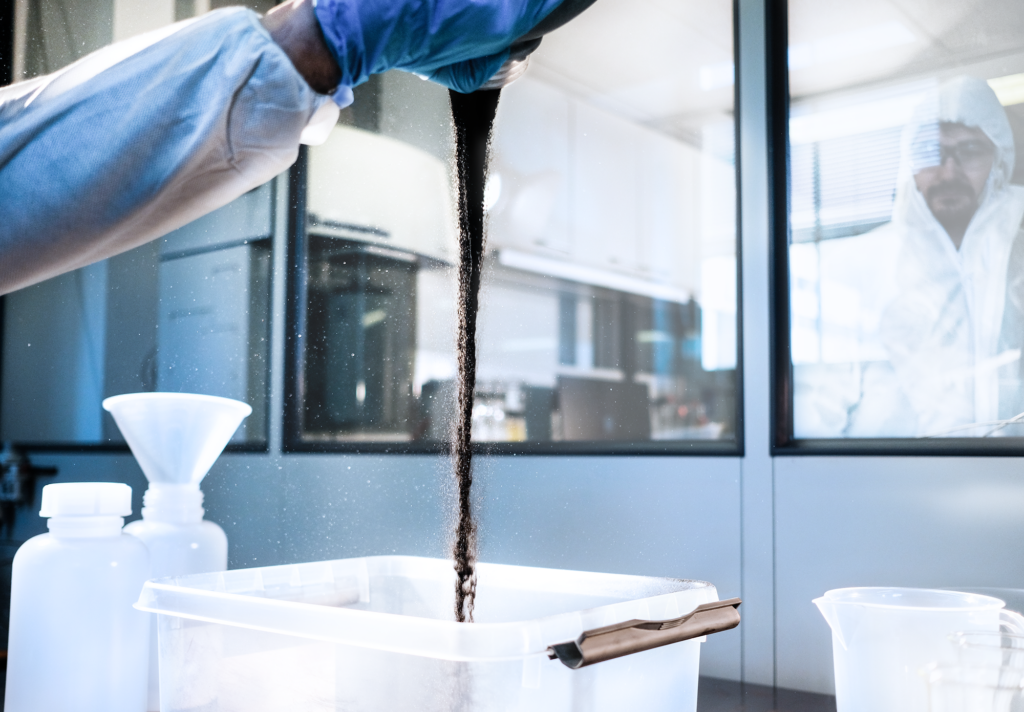

In the beginning, all their manufacturing happened in the corner of a small office.

The new team decided not only to focus on the material but also on a specific application, Madiberk remembers. “There is a lot of potential with novel materials, but the real key here is how to integrate them into technology,” he explained to Research in Estonia.

Infrastructure and manufacturing technology are often already in place, and it’s challenging to integrate new ideas into the old ways of doing things. One has to start from scratch.

To his advantage, Madiberk didn’t realise what he was getting into. Looking back, that’s part of the reason they may have been so courageous, he believes. “We thought it would take us 18 to 24 months to go through the deep technology development cycle,” Madiberk said.

It took them a decade.

Most ideas stay in the lab and never grow into big productions. Usually, because of money, but according to Leis, patenting your solutions is also crucial. Skeleton now owns a few dozen patents.

Two factories in Germany

Leadership matters too, of course.

“We use a system called key results, setting yearly or quarterly goal settings. It enables us to focus,” Madiberk explained on stage during the annual European Innovation and Technology summit, focused on deep tech. This EU institution was one of the first ones to back Skeleton financially, supporting its growth and development with €4 million.

In Madiberk’s view, there is a cultural problem in many deep tech companies. Changing people’s mindsets working for manufacturing is essential, he believes.

Skeleton now has two factories in Germany; it’s even working with British multinational oil and gas giant Shell. Next year, Skeleton will open the largest supercapacitor factory in Europe, producing twelve million cells a year.

As the new generation of engineers is taking over, the three Estonian scientists are remaining in their small town in Tartu where it all started.