Indrek Tarand is an Estonian politician and a member of the European Parliament. Born into a politically and socially active family (his father Andres Tarand served as Prime Minister of Estonia in 1994-95 and his mother Mari Tarand is a well-known linguist), Tarand studied history at the University of Tartu and as a student during the Soviet occupation, he was expelled in his first year for lighting candles with his fellow Estonian patriots on the grave of Julius Kuperjanov, a pre-Soviet Estonian military commander. Subsequently, Tarand was forced into Soviet military service. After finishing university in 1991, he has worked as a an advisor to the prime minister of Estonia and as the secretary general of the Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. After running as an independent candidate for the European Parliament in 2009, he secured a seat for himself with 25.8% of the total votes — a record so far in Estonia, and beating all political parties bar one along the way. Tarand is a member of The Greens–European Free Alliance parliamentary group.

I

Mr Tarand, you started your career as a public servant, but now you’re a politician. Do you feel that this is what you were destined to be — or is it rather a matter of coincidence?

Life is a coincidence in most general terms — first it takes your parents to meet each other under certain favourable circumstances and so on. But I would rather prefer not to be called a “professional politician”, because it is automatically correlated to the current status of “political class”. I have never been part of that, not in Soviet nomenclature sense, nor in the modern British meaning of the word. In Estonia, party politics is growingly associated with incompetence and even financial crimes, and ultimately with electoral fraud. That is a big concern for me and I consider it to be a threat to our democracy and independence. Hence my asymmetric actions on the political playground — I try to stop that downhill spiral and even to turn it to more promising paths of development. My decade in the civil service was also a coincidence — nobody wished to take a job in resolving the Narva crisis in 1993, but I felt that every Estonian citizen has an obligation to try their best for the country and serve the government, at least for a while. Of course I admired the “Yes, Minister” TV series too much and probably made significant mistakes during my civil service career as well. Yet in hindsight, I am still proud that I was part of the team that created the best functioning foreign service in former communist Europe. Those who fired me 13 years ago grudgingly admit today that without me the team is not always going to be playing at the same level.

You were elected to the European Parliament in 2009 with massive support — gaining the support of 25% of Estonians who voted. You joined the Greens in the EP, probably to the surprise of some. Looking back four years later, what do you feel are your accomplishments?

Well, that is exactly the politics as usual — one should praise himself rather than let the others to judge his achievements. But I have met all my targets that I set. This means I promised to use all the possibilities the Rules of Procedure provide. It is actually not too obvious that as a first-term member from a small country and a small political group, you will be able to write a report, speak on behalf of the group on some policy area or to run independently to the post of one of the 14 vice presidents of the Parliament. I will return home next spring with the Shield, not on a shield, like old Spartans would express it.

Ah, the Green group? This surprised some, definitely. But I have not made a secret that the Green imperative — to make an effort to save the planet and biodiversity — is more contemporary and relevant than political doctrines concentrating only on fiscal stability, labour relations or free market. So I did not surprise myself at least. Last but not least, the Greens did not ask me to join the party officially, which other groups were petting as a prerequisite.

What concerns the 25% of the vote, here we accomplished something extraordinary even the Harta12 and Rahvakogu could not — we changed the law back to open electoral lists!

By signing the Spinelli Group manifesto, you made your support for a federal Europe public. But in Estonia you have traditionally been associated with conservative, centre-right movements (such as “Vaba Isamaaline Kodanik”, for example) — the movements which place national identity above a European superstate. Isn’t there a contradiction and do you still support a federal Europe?

I did sign that manifesto because I wanted to be closer to the table where the federalist ideas were debated and discussed. Not perhaps so much in order to influence them really, but to get acquainted with the main promoters of them, to learn how they think etc. I also translated Guy Verhofstadt’s and Daniel Cohn-Bendit’s “Manifesto“ into Estonian to make it available to our public as well. That does not prevent me to be part of Vaba Isamaaline Kodanik and have a dialogue with more conservatively thinking people. Perhaps it is difficult to explain briefly, but for me federalism still has an appeal. It simply needs to be a different kind of federalism that we are practicing now. The institutionalist approach of Jean Monnet is probably not anymore as useful as half a century ago. But also the hidden treaty changes made by the member states’ governments without any discussion in the European Parliament must be stopped. Because they are actually dominated by the national agendas of bigger member states, leaving the smaller out in cold. My slogan for the time being is “No more institutionalism, we need innovation and idealism!“ And let the voters in all EU states decide which plan to achieve this is most likely to work.

When it comes to domestic politics, you have recently been very outspoken, criticising sharply the governing Reform Party, for example. Does it mean that we will see you back in Estonia by the next general election, as a candidate for a new party?

I don’t really think a new party is a proper response to Estonian problems. If we could somehow de-sovietise the existing ones and make them operate in better ways and according to demands of the 21st century, there would not be any need for a so-called new power. However, as the empirical evidence proves that without an existential threat to the consolidated nomenclature power they are unable to regret their practices and change anything, it is probably a kind of must-do for me. But I prefer it not to be a political party whose goal is to get elected and then remain in power whatever it takes. It should be (perhaps in legal terms a party, indeed) more like a project. We will promise to fix some core problems and also promise that we won’t seek re-election after that.

What solutions would you offer to solve the current image of Estonian politics, the feeling of mistrust towards parties and politicians?

I am working with many good and thorough thinkers and influential people to find a cure to this disease.

How well do you cooperate with other Estonian MEPs in Brussels? Is the atmosphere a bit more constructive than in Tallinn?

I cooperate as much as possible indeed. But volatility and a so-called “Angry Birds“ exchange in a liberal group makes it difficult. Siiri Oviir is an exception. I still find that there could be structural ways to get this cooperation better, but their domestic party political interest and selfishness is a disturbing factor. Sometimes politicians are very obstructive.

The public mood in Estonia is slowly turning more social democratic. What’s your opinion on this — is it a right time to dedicate more effort and funds to address the social issues or is Estonia still too poor of a country to do that?

Social democracy is not so much about richness and poorness but about equality and equal treatment. In that sense Estonia should look into imbalances of course. We can be more inclusive and more empathic towards our fellow citizens indeed. The nomenclature-parties (Reform and Centre) have unfortunately influenced the other players to behaviour as dishonest and arrogant as theirs. So I don’t see that labels mean anything. You can find as many dishonest members in the Social Democratic Party as you can find former nomenclature commies in Reform and Centre. And in IRL (Pro Patria and Res Publica Union), well, there you can find citizenship traders.

I“Estonia is not a poor country, the question indeed is, how the wealth is distributed. And as long as it remains distributed by the party establishment, a small group of top officials and business leaders, as long as 10% of the population is making their living abroad, I cannot be happy about the status of my country.”

Estonia is not a poor country, the question indeed is, how the wealth is distributed. And as long as it remains distributed by the party establishment, a small group of top officials and business leaders, as long as 10% of the population is making their living abroad, I cannot be happy about the status of my country. Let alone “be proud“ as the governing party tries to command everybody to be.

What do you think Estonia should do to attract young Estonians — tens of thousands who have left in last 10 years — back to their homeland?

Providing a social model that attracts these people is difficult, yet possible. First we have to get rid of the political stagnation, clientelism and sovietised methods of governance of every aspect of life. The rest comes with it naturally.

Finally — what’s your opinion on Europe’s future prospects? Are we right to worry about it?

Of course we should be worried. In times when the traditional security umbrella of the US is evading, in times when Europeans don’t discuss common actions, common values, Europe’s future, but prefer only to quarrel about money, we should be extremely worried. And work hard to find ways to improve the situation. This format is too limited to throw out some personal ideas about it, but we could talk about those specifically in nearest future.

I

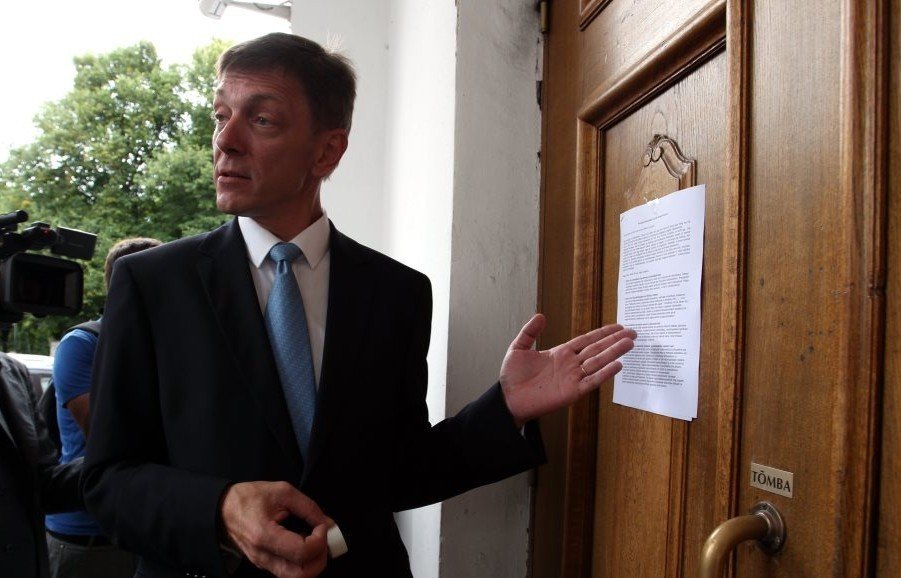

Cover photo: Indrek Tarand by Liis Treimann/Scanpix.ee