Having lived most of his life abroad, Viido Polikarpus returned to Estonia, the land of his ancestors, when he was 49 years old. He had been an officer in the US Special Forces and, as he says, “one of the first trained suicide bombers without knowing it”, but true happiness he found only in Estonia.

In 1995, when he had returned to Estonia, “I thought I had already lived out my life, but the most interesting period of my life had then just begun. I am sure the next 20 years will be just as eventful and rewarding.”

Today, Viido is 67 years old. He lives in the Estonian countryside, just outside the village of Kurenurme in Võrumaa. He was born at a refugee camp in Lübeck, Germany, and lived most of his life in the United States. He would be an ordinary Estonian man whose parents, like so many others in the aftermath of the Second World War, had to escape the advancing Soviet forces of occupation and make a life for themselves outside their beloved homeland, except that… he isn’t.

From Tallinn, Estonia, to Lübeck, Germany, to Lakewood, NJ

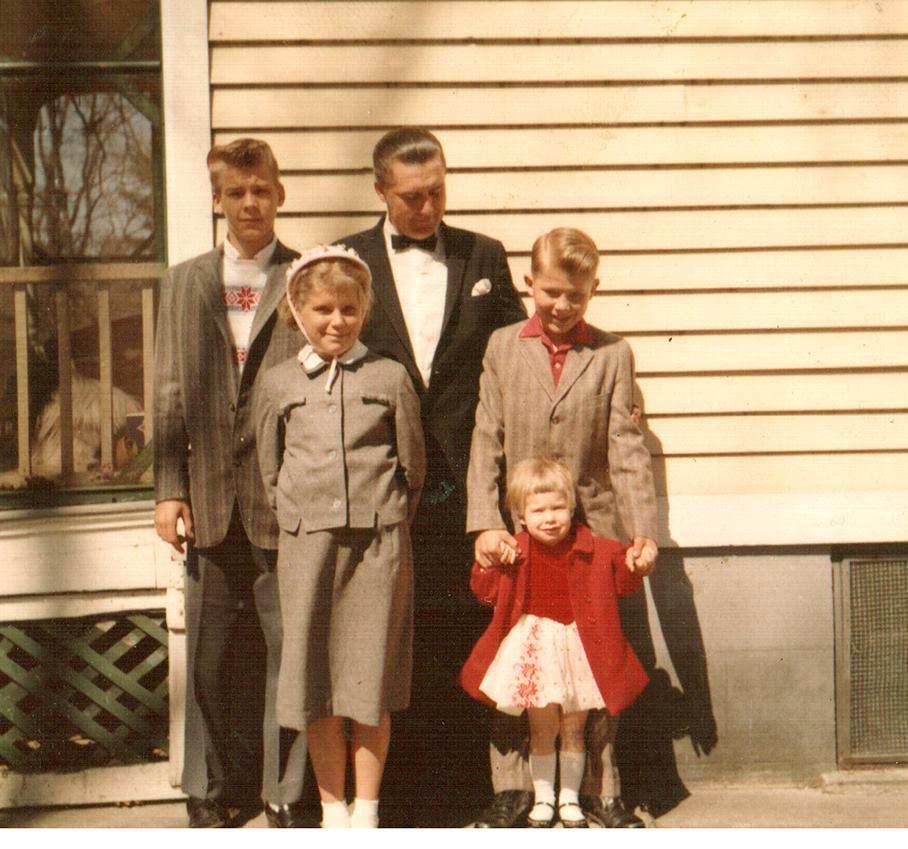

Viido Polikarpus was born on 7 July 1946, in a refugee camp as his parents’ second child. His brother Kaido was two years old and was born in Viljandi. Two years after Viido, in 1948, sister Irja was born, also at the refugee camp in Lübeck.

“My uncle Uno Polikarpus was one of the elite original Estonian pilots during Estonia’s first period of independence,” Viido tells his parents’ story. “With the German occupation, all pilots were simply transferred into the Luftwaffe, essentially doing the same job they were doing earlier, protecting Estonia’s shores from Russian pilots. In 1944, the Estonian boys were holding back the Russian army at Narva in the Blue Hills, and as one division of young Estonians held back 10 armoured divisions of Russians, they ultimately had to back up and come up from Tartu.”

“While this was going on, the Germans were evacuating their troops in Tallinn and those that could, tried to get on board the troop ships. My father was drafted into the German army but deserted and then was imprisoned but escaped. My mother’s name was the same as my uncle’s, so when she was trying to get on board the troop ship, they asked whether she was Luftwaffe Lieutenant Polikarpus’ wife, and my mother said yes! My mother and brother were allowed on board. My father managed to get to Germany much later.”

The family moved to the US in the summer of 1951 and young Viido went to kindergarten at the Ella G Clark school in Lakewood, New Jersey. In 1964, he started college at Monmouth. “I have always been the best artist in my class so I expected to study art,” he says. But fate had other plans for the young Estonian.

“After a year of earning money for school, partying (which caused a lot of tensions with my father at home) and seeing all my friends doing everything they could to avoid the draft, I naturally quit college and enlisted in the army. I was determined to prove to my father that I was someone. I was determined to come home with medals or in a box. Either way I figured I would win!”

On to save the world from communists

Life has a way of playing tricks with us. And it did play with Viido’s, too – only two decades after being born as a refugee in Germany, he returned there as a member of the US Special Forces.

Even though he wanted to go to Vietnam, the Special Forces needed officers to fill many vacant slots around the world. “They probably assumed I spoke German as well,” Viido points out, thinking back. Nevertheless, “I was very disappointed when I received my orders” to be assigned to Germany. After all, he had successfully completed the programme of the Infantry Officer Candidate’s School in Fort Benning, Georgia, in six months, and wanted to go to Vietnam to “prevent the dominos from falling and save the world from communists!”

Even though he went to the Pentagon three times in uniform, trying to get them to change his orders, there was nothing they could do. So Viido had no other option than take up his assignment – attend the Special Forces qualification course given by the 10th Special Forces Group (Airborne) 1st Special Forces in Bad Tolz, Germany.

“The first trained suicide bombers without knowing it”

Everyone in the Special Forces has specialties. “I was the SADM officer,” Viido says, SADM standing for Special Atomic Demolition Munitions. “I was trained to parachute a small atomic demolition munitions behind enemy lines and then detonate a rail complex, a dam, an airport, whatever the military needed to be got rid of behind the enemy lines, expediently, of course.

“We were trained to plot our escape route with a cardboard plotting chart allowing enough time for me to escape the blast and fallout. When the time needed [until detonation] was determined I then had to set a timer clock located next to the slot where I would place the arming device,” he describes his assignments.

“In reality, why would the military risk compromising a small nuclear device just to allow one person to escape? All things being equal, the moment I would be setting the clock, everything else would be in place. I believe I may have been one of the first trained suicide bombers without knowing it.” Fortunately, Viido had luck on his side, and besides: “My training back then was so expensive that a major at the Pentagon told me during one of my visits the last thing the army would ever do would be to place me in harm’s way. I was too expensive to waste!”

Back to school and the world of arts

As badly as he wanted to be a hero, Viido never got to go to Vietnam. “The fact that I so wanted to prove myself probably kept me alive and out of the box I so wanted to come home in.”

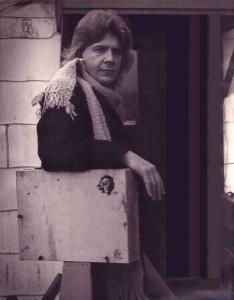

He returned to the US, but became disillusioned with the military, as he puts it. So in June 1969, he left the army as a 1st Lieutenant and moved to San Francisco where he got accepted to the San Francisco Art Institute. “I attended there for a couple of years, remembering very little. I then attended the New York Art Students League and finally re-entered Monmouth University and finished ten years after starting there to get a double BA in Creative Writing and Fine Arts.”

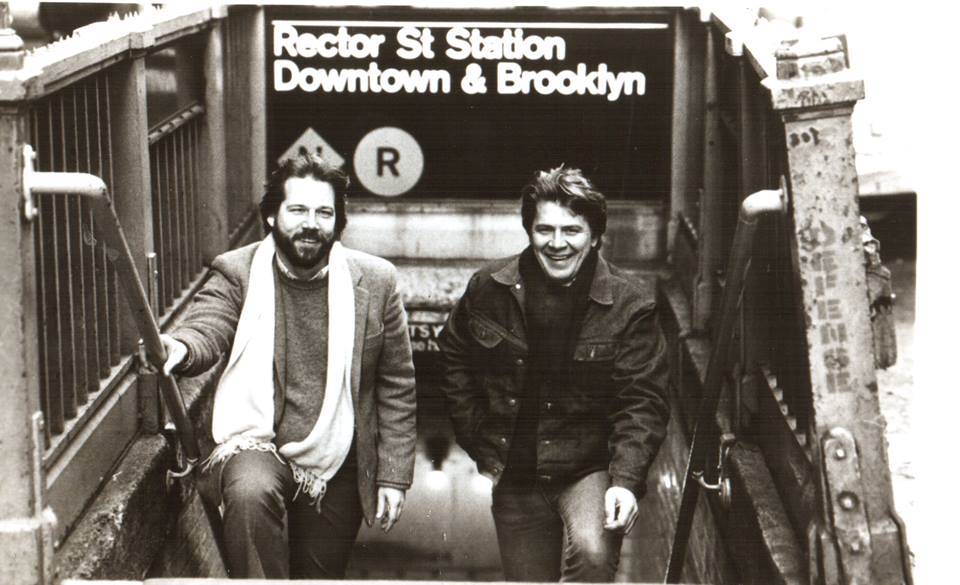

At that time he met his first wife Carolyn, had a daughter Maarika and adopted a son, Eerik. “I wanted to illustrate children’s books because it was very lucrative, but when I went with my portfolio I was told the money was in the writing, not illustrating. So I wrote “Down Town”, a children’s book with lots of illustrations. Arbor House bought the rights but being sure it would make a great movie, they asked me to rewrite the book making the protagonist 14 instead of nine. With the help of Tappan King, a copywriter, we finished the book on schedule and it was published.”

The book did well and was chosen by the New York Public Library as one of the top 300 books of the year in 1985. “At the same time, the Art Directors of New York gave me an award for the cover artwork for the hardcover edition.”

A film producer once wanted to make a movie based on the book, “but I said no because they had only made break dance films up to then, and I was waiting for George Lucas or Steven Spielberg to make me an offer. They didn’t and the small company I refused back in 1986 was TriStar.”

Interestingly, Viido also wrote and illustrated a children’s book based on the Estonian fairy tale, Kaval Ants ja Vanapagan, which he translated into “Sly and the Ogre”. He had a dream of having Disney “doing wonders” with it, but this dream was not meant to be.

Rediscovering one’s roots

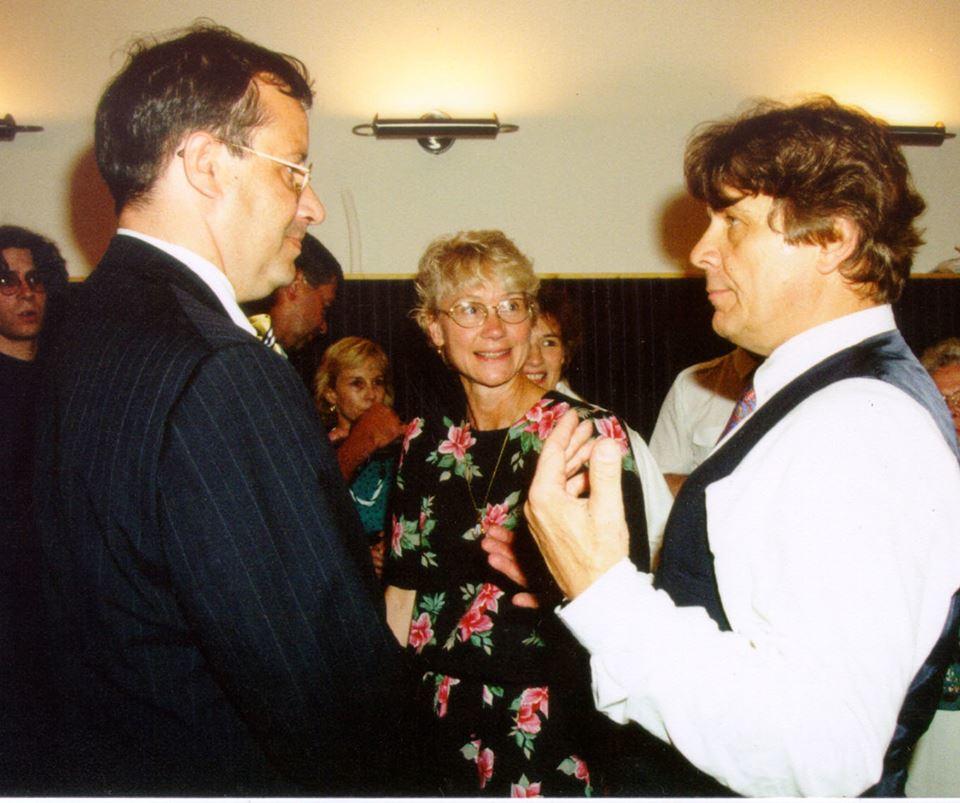

After working in New York with handicapped children and being in charge of a programme to teach the homeless of the Big Apple to do construction work, Viido was invited to become the manager of the New York Estonian House. “When I was there in 1994, exciting things were happening in Estonia. While managing the Estonian House I became acquainted with several important Estonians who always made a point of stopping there. I hosted several events for the Estonian Ambassador to the United Nations, Trivimi Velliste, with whom I became friends. During one event, the Commander of the Estonian Defence Forces, Aleksander Einseln, invited me to come to Estonia, saying: ‘I could use a man like you in Estonia!’ I told him I would come and did, three months later.”

General Einseln made Viido an advisor and gave him the pay grade of a colonel. “I didn’t take Estonia or Estonians very seriously when I first got here. It was all like a caricature somewhere. I would imagine anyone who had never been to New York would have seen so many films and TV shows with scenes of New York, that once they were there, many things would seem surreally familiar. I grew up looking at picture books of Estonia so whenever I saw a church somewhere it was familiar, a castle, a tower, but how they fit it with the overall picture I didn’t know. I expected to stay in Estonia for one year and then return to the States.”

Viido remembers that Estonia then was very much like the early episodes of the Estonian Public Broadcasting series Õnne 13 filmed when he first got there. “You get the feeling of the sombre darkness of the city and the general ramshackle existence which permeated everything, representative of a failed soviet state. But I loved it, it was all exciting. Whenever I had coffee at the Narva café across the street from the General Staff Headquarters, I imagined Russian agents and Mata Haris everywhere. I especially lucked out when General Einseln had a lady called Heli Suviste share my office, who then became my wife. She still works at the General Staff Headquarters today.”

Into the restaurant business

When General Einseln left his post as the Commander of the Estonian Defence Forces, Viido found a job as the general manager of George Browne’s Irish pub in Tallinn. He soon transformed the pub from the brink of bankruptcy into a flourishing establishment with his management skills and, most importantly, good taste in music – “I replaced the techno beat music with Eagles-type music and introduced classical musicians to the Victoria Lounge on the second floor. I had constant live classical music playing.” Soon, the business was doing well.

Being the manager of a famous Old Town pub gave him yet another idea. “George Browne’s was where a group of expats would meet once a week to drink beer or wine and just chat. They called themselves Eesti Maja (Estonian House). I saw right away what was needed. If an expat travelled to Toronto, New York, Sydney, Stockholm, they would always stop at the local Estonian House, to let everyone know they were there. But in Estonia whenever anyone would arrive from New York or Toronto, as so many were doing every day, often no one would ever know who else was in town.”

With some partners and financing from a friend, they leased a basement space next door to the foreign ministry and proceeded to dig out and build a good-sized restaurant – the Tallinn Eesti Maja. The cellar restaurant offered authentic Estonian food – if there is such a thing – and became popular among Estonians and visitors alike. Unfortunately, just when the 15-year lease of the place was up, the economy plummeted and it became more and more difficult to maintain the restaurant.

“If I had to do it all over again, I would have purchased a place for Eesti Maja instead of leasing the space,” Viido says. “But back then money, as always, was scarce.” He had already opened another Eesti Maja restaurant, but that had exhausted his resources. “With hundreds of new restaurants opening each week, add on the economic downturn and the slackening of tourists and expats, we had little choice but to close shop.”

Becoming a ‘Jehova’s Witness’ of solar energy

Already at that time Viido was working on developing solar energy in southern Estonia. When a Hungarian-Estonian called Michael Wegescany had many years earlier come to Estonia and bought a farm right near where Viido lives in the village of Kurenurme, the two men became friends. “He worked in Australia in the solar industry and so we started talking about why there was so little investment in solar energy in Estonia compared with, say, Germany and Poland where there was considerable investment. I started looking into it and began to read more and more about solar power.

“I became like a ‘Jehova’s Witness’ on the subject of solar power. The more I researched things, the better the situation became. We decided to set up a company, Michael came up with the name – Energy Smart – and I started meeting with members from the Tallinn Technical University as well as the Estonian Meteorological and Hydrological Institute who only confirmed the fact that Estonia had more solar resources than Poland or East Germany, yet they had already invested millions but Estonia not one red cent.”

After having bought German solar trackers – devices that orient solar panels toward the sun – the men talked the government into subsidising their project with 70% financing. “Estonian farmers can produce clean energy into the grid in lieu of depending on EU agricultural subsidies. Latvia agreed to purchase all the solar energy we can produce. Latvia needs to purchase energy in the summer months when the water capacity in their dams is low. Latvia gets 70% of its energy from hydro.”

Fighting the local energy monopoly

As Viido points out, in every EU country where solar energy has been introduced, the biggest enemy has been the local energy company. “Eesti Energia [Estonia’s largest energy company] is very powerful here in Estonia. Since it is difficult to monopolise solar energy, Eesti Energia is apparently not interested in its development here.”

At the beginning of the project, Eesti Energia had told the solar energy pioneers it would cost about 20,000-25,000 kroons (€1,280-1,600) to hook them up to the grid. “We have applied several times over the years for commissioning, the first time was four years ago. Eesti Energia told us a year later that they had lost our application. The second time we applied, a secretary had locked our application in her desk and she was on an extended vacation. The third time our application was returned because Eesti Energia had a new application form and we needed to fill out a new one. By the time we got a written response for our application, it was autumn of last year and we discovered Eesti Energia now wanted €50,000 and 330 days after payment to comply to hooking us up.”

Now they are looking for ways out of the problem: “No one wants to drop €50,000 into Eesti Energia’s pocket just to sit for a year while they could easily be coming up with another reason why they won’t hook us up. I do not trust EE anymore.”

Enjoying Estonia as an Estonian-American

The solar park is 100% ready, Viido confirms. “My partners and I have finished what we set out to do: we have built the first solar power plant in the Baltics and the biggest array of solar panels in Estonia. If politics had not got in our way, we would have been operating years ago. Now I am just waiting to see what will happen.”

So what now? Well, Viido is “painting and writing and enjoying my life in the country. I came to Estonia when I was 49 years old. At the time I thought I had already lived out my life but the most interesting period of my life had then just begun. I am sure the next 20 years will be just as eventful and rewarding.”

Who does Viido consider himself to be? An Estonian? An American? “In the United States I was considered an Estonian, and here in Estonia I am considered an American. It has been this way all my life. I appreciate it for what it is. When someone calls me a väliseestlane (expat Estonian), I am not offended like many of my friends here often are. I consider it merely an identifier. It merely clarifies why I am like I am. I am an Estonian-American.”

I

Cover photo: Jumping into the Bavarian Alps in the middle of winter, which is why the guys are carrying bear paw snow shoes. Taken by one of the sergeants. Viido is on the left, his team sergeant of A-17 Master Sergeant Baird on the right. From Viido’s private collection.

Great post! I met Viido about 10 years ago in Tallinn and he’s a great guy. It’s a shame his Eesti Maja restaurant had to close. I used to eat there all the time.

Great story. Working in the solar pv industry in the UK, I deal with energy companies all the time. Although I am suspicious of their respective boards manipulation of the market, I get none of the incredible hassle reported here. I have a feeling that the cost of connection in terms of linking and upgrading substations is what this is all about. Shame you don’t have an energy regulator in the government

A few questions:

Why not consider stand-alone?

If you are close to the Latvian border, would the Latvians consider buying direct? They may quote cheaper to connect to.

It’s a sad state of affairs when you are at the mercy of intransigence, but don’t give up!