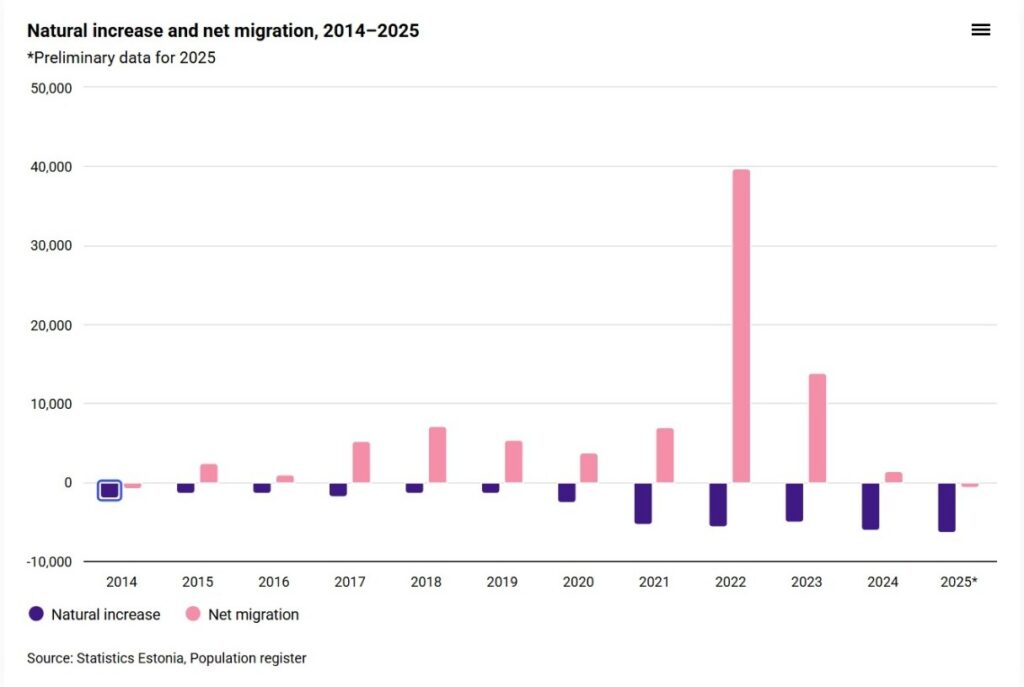

Estonia’s population shrank by 7,041 people last year, according to preliminary figures published by Statistics Estonia, marking another sombre milestone in the country’s long-running demographic slowdown.

As of 1 January 2026, Estonia’s population stood at 1,362,954 – down from a year earlier – reflecting a familiar but increasingly stark equation: too few births, more deaths, and, for the first time in over a decade, more people leaving the country than settling in it.

In 2025, 9,092 children were born, while 15,427 people died, leaving a natural decrease of more than 6,000. Net migration also turned negative, with 11,298 arrivals and 12,004 departures – a deficit of 706 people.

Kadri Rootalu, service manager of population and education statistics at Statistics Estonia, said the trends of recent years had simply continued. “Last year, over 6,000 more people died than were born. Emigration remained at the level of 2024, but immigration decreased. Net migration was negative for the first time since 2014,” she said. “Altogether, Estonia’s population declined by 7,041.”

Births fall below 10,000 – again

The number of births fell by six per cent compared with 2024, making 2025 only the second year in Estonia’s history when fewer than 10,000 children were born. Rootalu noted that while the decline continued, its pace slowed. “In 2024, births dropped by more than 1,200 compared with 2023 – almost 12 per cent. These indicators improved last year,” she said.

Demographers point to structural causes rather than sudden shifts in family behaviour. The number of women aged 20–44 – broadly considered childbearing age – stood at around 210,000 in 2025, some 10,000 fewer than a decade ago, although the figure has stabilised over the past three years.

Similar patterns are visible across the region. Birth numbers also fell sharply in Latvia and Lithuania, while Finland recorded a slight increase during the first nine months of 2025 – though from historically low levels.

Deaths, meanwhile, declined modestly. The 15,427 deaths recorded last year were around 300 fewer than in 2024 and broadly in line with the pre-pandemic average of 2010–2019.

Migration balance turns negative

Perhaps the most politically sensitive shift was in migration. For the first time since 2014, more people left Estonia than arrived.

Roughly 35 per cent of immigrants – about 4,000 people – were Ukrainian citizens, a figure that continues to fall as the initial wave of war-related migration recedes. By comparison, 33,200 Ukrainians arrived in Estonia in 2022, followed by 13,100 in 2023 and around 7,000 in 2024.

Rootalu added that preliminary data also suggest negative net migration among Estonian citizens themselves, although over the past decade their overall migration balance has been broadly neutral.

Statistics Estonia will revise the figures in the coming months by incorporating data on unregistered migration, which will determine definitively whether 2025 ends up recorded as a year of net population loss through migration. Even so, the direction of travel is clear: Estonia’s demographic challenges are no longer cyclical, but structural – and increasingly difficult to ignore.