The Estonian Drama Theatre is making a clear pitch to Estonia’s international community, expanding the number of productions available with English and Russian translation in a move that underlines the theatre’s ambition to remain culturally central in an increasingly multilingual society.

From February to April, three major productions will be accessible to non-Estonian speakers, with English subtitles or bilingual English–Russian translation. A limited ticket reserve has also been set aside specifically for foreign-language audiences, signalling that the initiative is more than symbolic.

Theatre-goers will be able to follow Once in Lebanon with English subtitles on 4 and 5 February; 19 and 26 March; and 10, 25 and 27 April. Meanwhile, Eisenstein (20 February; 14 and 16 March) and The Totalitarian Novel (9 and 10 March) will be performed with both English and Russian translation.

At the centre of the programme is Once in Lebanon, a tense political thriller inspired by real events. It begins on 23 March 2011, when Lebanese police discover seven touring bicycles abandoned in a roadside ditch. Among the items left behind are Estonian ID cards. Within hours, a crisis meeting is convened at Estonia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Tallinn. It soon becomes clear that the country is facing its first hostage crisis involving Middle Eastern terrorist organisations. The production asks an unsettling question: when citizens are taken hostage abroad, where does a small state even begin?

The stage text is based on the television series Trading Life, developed by Ove Musting, Mehis Pihla and Siret Campbell, and Tiit Pruuli’s investigative book Anti-Lebanon.

Eisenstein turns to the moral compromises of art under dictatorship. Set in 1941, it imagines the moment when the Soviet film director Sergei Eisenstein receives a personal offer from Stalin to make a film about Ivan the Terrible. Refusal is impossible; compliance is corrosive.

The play, by Russian dramatist Mikhail Durnenkov, now based in Helsinki and a leading figure of the oppositional theatre Teatr.doc, explores these choices through the eyes of young NKVD officers assigned to keep Eisenstein under surveillance. Created in close collaboration with actress and director Julia Aug, who emigrated from Russia to Estonia, the work is an attempt to understand the roots of authoritarianism in today’s Russia – and why it seems so resistant to ending.

The most overtly political of the three, The Totalitarian Novel, draws on the legend of the mankurt from Kyrgyz writer Chinghiz Aitmatov: a human being stripped of memory through violence and thus rendered obedient. Lithuanian playwright Marius Ivaškevičius uses the myth as a prism through which to examine Soviet terror, Stalinism and the brutal absurdities of post-Soviet dictatorships in Central Asia. The play was prompted by a real conversation with a Tajik theatre director whose production Mankurt was banned in 2022 shortly before its premiere, while one actor was sentenced to ten years in prison.

The piece weaves together that contemporary repression with echoes from the Soviet past, the fate of artists crushed by power, and figures from Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita. It is a co-production between the Estonian Drama Theatre and Vaba Lava, supported by Allan Kaldoja.

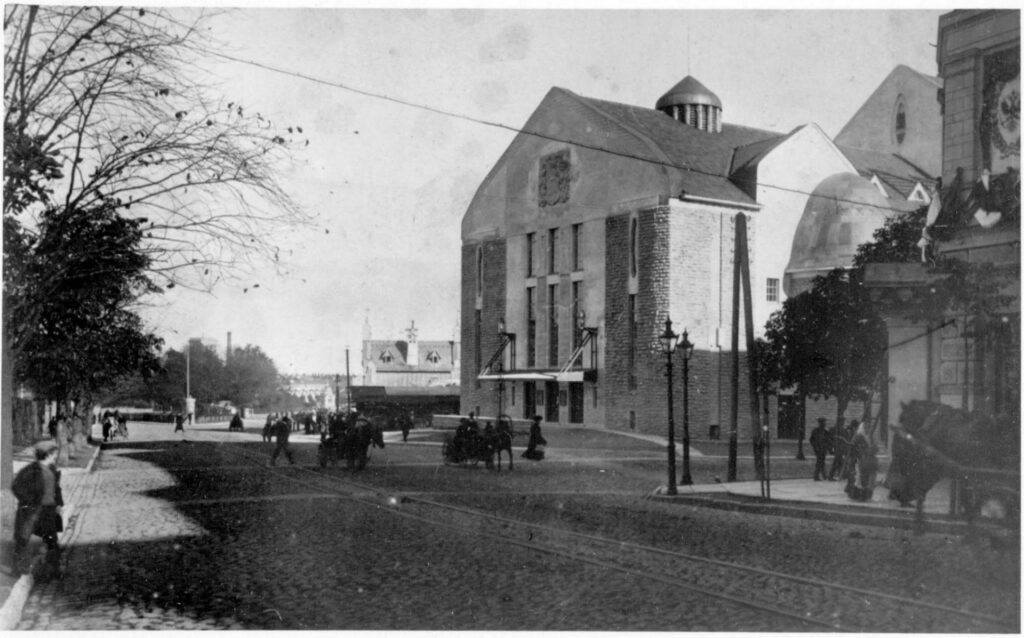

Founded a century ago, the Estonian Drama Theatre has long functioned, in practice, as the country’s national theatre. It traces its roots to Paul Sepp’s private drama studio, established in 1920, and has operated since 1910 in the Art Nouveau German Theatre building in central Tallinn – the oldest surviving theatre building in Estonia. Today it is the country’s largest spoken-word theatre, with a permanent ensemble of 37 actors, more than 20 productions in active repertoire, and over 500 performances a year, seen by more than 100,000 people.

By extending translation and actively courting foreign-language audiences, the theatre is making a pragmatic and quietly political statement of its own: that serious theatre in Estonia should be open not only to the nation, but to everyone who lives within it.

Tickets from the reserved allocation can be purchased via the theatre’s sales manager at elen.jaaska@draamateater.ee.