Heiki Trolla, better known by his artist name Navitrolla, is among the most well known Estonian artists whose work has been described as naivist or surrealist. Most of his works depict fantastic landscapes and animals. He spent his childhood in the villages of Trolla and Navi near the Estonian town of Võru, which is the source of his pseudonym. EstonianWorld had a candid evening discussion with Navitrolla at his gallery, in the Tallinn Old Town.

I

“My mum told me that when I was half-a-year old, I opened my pants, took my own shit, and made a fresco on the wall. I really don’t remember. It seems to me that inner wishes and feelings always pointed towards doing art.” It was an odd start to any interview, but the Estonian painter Navitrolla, who became famous in the early 1990s for his surrealist landscapes, was making a joke, which may have been true, in response to a question about the first time he had noticed an artistic inkling.

As a young man, Navitrolla, now in his forties, was brought up as part of a farming family in Navi, southern Estonia. “In Soviet times, people were telling us to take normal jobs, and farming was the only option for me – work, work work! Make money, go to the army, have kids, take the pension, die. But I was absolutely against this model of life. I believe there can be options for freedom; you can live as you wish. I cheated my mum every day; I took textbooks and I told her, ‘I’ll go to study, sorry I can’t feed your pigs or cows’, and I went to the field. There was the smell of dry hay, really beautiful flowers, and I put my textbooks next to me and just tried my best to be away from serving animals.”

Although others might have recognised a latent talent, Navitrolla first viewed art as an escape, never taking it seriously. “When I started in art, it seemed really funny, a big joke. But I’m getting older and older, and I see [art is] a serious thing. People are living and not willing to dream. I don’t want to be a teacher, or a guru, or whatever, but through my simple paintings, maybe I can… I don’t want to tell you a serious story – I am not a philosopher – but through my art, maybe I can tell people something.”

The idea of the artwork sending a message was an interesting one, given that Navitrolla’s cartoonish landscapes could be said to inhabit a singular mind, entertaining itself. “There are many things I would like to teach… When I’m describing my experience through life, like in that black and white reproduction in the corner,” he explained, showing a print on his studio’s wall, “when a boy is willing to go to the city and describe his experience using mushrooms, the idea is bigger than the painting. The painting is small, and it took two or three days, but the idea is that we dream of a white, bright, good life, but actually,” he expresses a strong opinion, “we are living in shit.” This may or may not be true, but it was a relief to find an artist willing to express such a strong view openly.

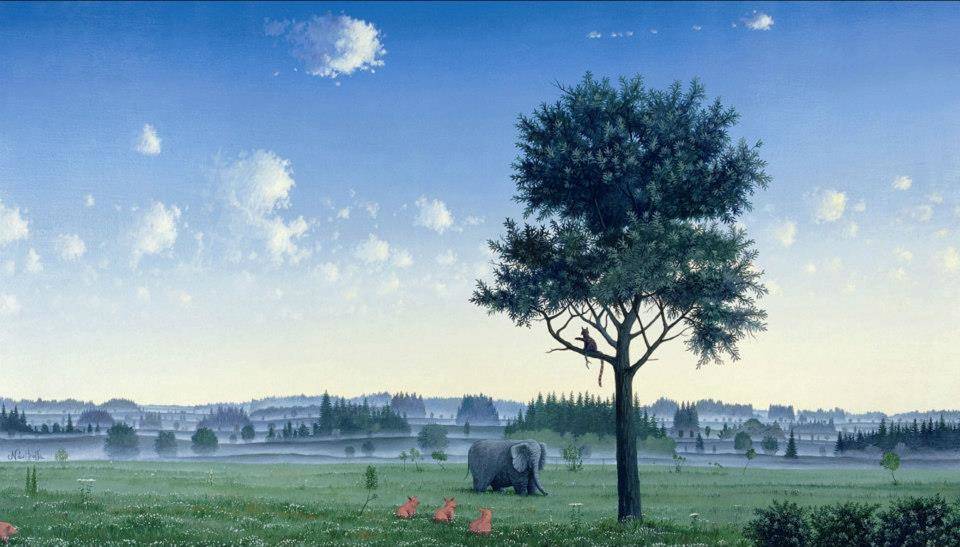

Some have remarked that his works seem like they had been imagined during dreams. It proved to be, at least in some cases, true. “This painting, [he gestured] ‘Christmas Night Dream’, came from a dream. There are also other works that came about when I was sleeping. When I’m dreaming when I’m awake, it’s a different thing – composing, constructing, creating things, like Lego. I’m trying to create this perfect idea of a world. But is it worth living in my world?” The artist then answers his own question. “No. People say to me, it would be nice to live in my world… but I’m not so sure!”

The stereo system, playing music from the 1950s to the 1970s, on all of which Navitrolla demonstrated a deep knowledge, moves onto the Righteous Brothers’ classic ballad, “Unchained Melody”. It seems to fit the profundity of our discussion at that stage. He talks about a painting on an easel, possibly showing three huge mountains in the desert, spewing clouds like natural power stations. “Every person creates his own idea of that picture. But this is an unfinished painting! I’m trying to create an impression of being Atlas… the man who carried the world on his shoulders. But how that will come across, it’s not decided. It’s unfinished.”

He goes on to explain about his parents. “I always had a nice relationship with my mum; she always said, ‘show whatever you want, the most important thing is that you’re satisfied’. My father? We just didn’t talk too much. He was a good father, I was happy with him. I went to school, I got these papers, and I told my mother and father, ‘right, so I’ve got these papers, so, erm, ciao!’ My father was a little angry, but my mother asked if I needed any money. I said ‘food is enough’.”

“We met five years later. My father asked my mother, ‘what is he doing? Is he stealing?’ My mother replied, ‘I’ve heard he’s doing art or something, but I don’t really understand it – but he’s doing good’. Once I came home with a car, at the end of the Soviet era – that was a sign of a good position in society. And it was only then that my father was very proud of me. Please try to understand there are so many hidden layers to the life of Estonian people.” Navitrolla also gives out the impression of a man who also wanted to make sure he did not cause trouble through careless talk. “I was the master of the mind game, to try to understand what was going on.”

He mentions repetition as the key to his success. “I am not a talented artist. I just try to do things again and again.” But many people would disagree and say he had a natural talent? “I NEVER say that myself. Other people say it. I don’t.”

While talking about the end of the Soviet period, which brought an influx of new artistic and musical influences to the attention of all young Estonians, that the interview hits something of a difficult patch. “We had a whole generation; a generation without roots. Waiting – floating creatures, waiting for a message… I understood very big changes would come.” However he refuses to be drawn on his feelings about the compromises of Estonians after the restoration of independence, feeling it was not the place of an artist to make political pronouncements.

He does, though, tell a tale about his school days, to show how things had changed since Soviet times. “I was a ten year-old boy, and one day we drew Estonian national flags before we went to school, but we didn’t know how, so we drew them the wrong way round. After that, all the schools were checked, because Võru was a closed, army town. Nothing came out.” But there was contradiction in the teaching. “Our history teacher said, upon hearing about our activity, that the Republic of Estonian hadn’t existed before, and the flag didn’t exist.” Navitrolla’s former teachers evidently felt freer to express any nationalist sentiment after the fall of the USSR in 1991. It gave the artist a feeling of political and personal beliefs being transient. “Ten years later, I noticed that these same people, those who said that the republic hadn’t existed before, were on the streets, cheering! And through that, I realised life was so… damn… relative.”

We finish after what was an intriguing discussion, spanning a variety of topics, with Navitrolla explaining what legacy he felt his art would have. “The side of creativity that always amazes me is that nothing remains, only ideas: we can’t put attention on these frames, canvasses, gallery and everything – when you go out, what remains? Not the gallery. Ideas [are what remain]. Those, for me, are the most important things.”

I

More information on Navitrolla: navitrolla.ee

Cover photo: “If All the Mushrooms in the World Would Be United”, Oil on canvas, 2005 (Navitrolla)

Wonderful article—so interesting on so many levels

Good Job Stuart