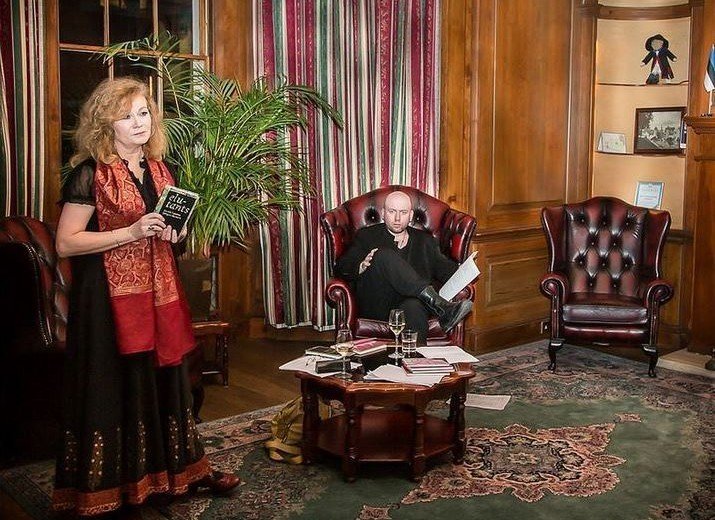

On 21 January, acclaimed Estonian poets Doris Kareva and Jürgen Rooste presented their recently completed collaborative work “Dance of Life” before an international audience at the Estonian Embassy in London.

The book, written over a two-year period, contains 24 dialogues or ‘dances’ between ordinary individuals and a personified ‘life’. The poets explained that this was a modern take on the medieval concept of a personified death – one could interact with it the way one would interact with a person. The dances are expressed as poetic dialogues, in which Kareva and Rooste each wrote one of the characters in each dialogue. The book does not credit the authors individually, leaving it up to the reader to decide which character’s dialogue is written by which poet. Rooste told the audience that whenever readers have ventured a guess as to the author of a particular dialogue, they almost always guess incorrectly. An added dimension to the project is a recent musical score in the style of an orchestral Latin Mass, written in conjunction with the poems.

After reading several “dances” in Estonian and English, Rooste and Kareva read some of their individually authored poems, giving the audience a glimpse at two very unique styles of contemporary Estonian poetry. Rooste’s poems are often charged with political and social commentary, which is rife with satire and often laugh-out-loud humour, evoking surreal yet unambiguous social messages. Rooste’s highly dramatic reading style evoked the charisma of a rock star on stage. There was no doubting the sincerity of his passion for poetry as he read.

Kareva’s poetry also concerned itself with world events, but where Rooste offered poems which commented on political and social developments, Kareva wrote about individual interactions with the world on a metaphysical and spiritual basis. Dreams, questions of being, internal development and emotional exploration are all thematic elements which sculpt Kareva’s poetry. In addition to employing psychological and emotional themes, her work reveals her as a great observer of individuals and the habits, hopes and dreams that shape their existence. Kareva’s reading style is thoughtful and contemplative and whether reading in Estonian or English there is a clear metre to her words, which add a rhythmic cohesion to her ideas.

“Rooste compared a spirit of malaise among the Estonian youth to Joe Strummer’s song (performed by ‘The Clash’) ‘Lost In The Supermarket’. He said that rather than meeting in clubs, galleries or music venues, kids hang around supermarkets and shops instead, something he found was culturally detrimental.”

After the reading, members of the audience asked questions to both poets. Rooste said that his initial inspiration to write poetry came from his lifelong love of music, in particular Estonian punk-rock, The Doors, Bob Dylan and also the American Beat poets. This led me to ask if he felt that rebellion was a necessary characteristic for a poet. In Rooste’s case the answer was “yes”. Rooste said that since the economic crisis of 2008, the youth of Estonia has become more placid, although he felt today’s social situations can be best addressed with poetry containing a punk-rock spirit of rebellion, rather than the calm of classical love poetry. Rooste compared a spirit of malaise among the Estonian youth to Joe Strummer’s song (performed by “The Clash”) “Lost In The Supermarket”. He said that rather than meeting in clubs, galleries or music venues, kids hang around supermarkets and shops instead, something he found was culturally detrimental.

Kareva said that one does not need to be a rebel in order to be a convincing poet but inversely, in certain circumstances penning a classical love poem can be an act of rebellion even though it is generally not understood as such. Kareva said that poets see what others see but they see these things as though for the first time. Thus in reading a poem one sees the known world through fresh eyes and this renewal of perspective is an act of rebellion.

“Kareva said that poets see what others see but they see these things as though for the first time. Thus in reading a poem one sees the known world through fresh eyes and this renewal of perspective is an act of rebellion.”

When asked why they write poetry, Kareva stated that writing poetry is like an addictive drug, but fortunately one that is healthier than most other drugs. For Kareva, poetry offers the highest sense of ecstasy in her life. Rooste said that writing poetry is like a kind of sickness but one which he believes produces art that is necessary for the world.

I later interviewed Jürgen Rooste to further explore some of the themes he raised during the Q and A session.

Describe the relationship between music and poetry?

For me the relationship comes from my youth, the first poets for me were rock ‘n’ roll heroes, starting with Jim Morrison, John Lennon, Bob Dylan and John Lydon, but also Björk for instance… probably the first “real” poems I wrote were some of Björks lyrics translated to Estonian when I was about 14 or 15. But actually all poetry, from its roots, somehow comes from music and songs, chants, chorales, curses. Not that I don’t recognise the importance of some modern poetry which is really meant to be read from the paper. New mediums like Facebook also change a lot. But at its origin, for me, poetry is meant to be a song or recited out loud like a kind of prayer. Maybe that’s the reason I’ve been so fond of beat poetry also.

Do some styles of music complement poetry better than others?

I’m not sure. As I was growing up, it was a lot about punk for me – punk poets seemed to be the most honest, they really meant something with their words. Nowadays I tend to work with jazz and blues musicians, but basically I can’t really say. Are rap and hip-hop a type of poetry? Of course! Language wants to live, it evolves and it nests anywhere it can.

When did you write your first poem?

I tried something in pre-school, it was kind of classical poetry. Later on, in high school, I started to write consciously, because I liked a girl who liked poetry. I liked her a lot! Then I got stuck with it, like an addiction, a sickness.

Is your poetry always a statement of your true feelings?

I hope so. It can also be a game, a play, a role and I might use other voices to tell important stories. But I believe poetry has a value, has a different position – I tend to tell stories and I tend to come out with statements which need some kind of special honesty. But it’s only one way to do it.

Is humour a crucial aspect to your poetry?

Laughter sets us free, but some of my humour is also very sad. It’s important to touch different places inside a human being. Places that other things or people don’t touch. Poetry is sometimes quite like making love.

You mentioned at the Embassy that you enjoyed having your poems translated into other languages as it gives birth to a new poem each time it is translated. How many languages have your poems been translated to?

I think it’s about ten languages, but books have been published only in Finnish, Swedish and Udmurtian. A collection is ready in German but publishing houses have not been too interested. I know they have almost a full book in Russian, Latvian and in Dutch, and some things in English, but these have not been published. There are several other translations, but it’s always a long way to go to get published in a manner that people can find and read. Which would be important, which would be great.

Are there certain cultures outside of Estonia you think would respond better to your work than others?

Of course, my second language is Finnish and second mental home is Finland. I sometimes feel like a Finnish poet because of my themes. And friends. And also, I felt at home in the southern American states, such as Louisiana and Tennessee and especially in New Orleans. But I don’t know whether they’d accept me as a poet.

Music has been said to be an international language. Is it ever possible for poetry to be a universal language in spite of translation barriers?

I think it is. On one hand, it always about language – some of the best poems are untranslatable. But still, I grew up reading Lord Byron in Estonian, and Pushkin and Mayakovski who was one of my favourites and my Russian is mediocre – rather lousy, in fact. Not really enough to “get” all the poetry. I have translated some Allen Ginsberg and some Kerouac, and I’m dreaming about William Blake but I’m not sure I’m good enough. Also Pentti Saarikoski from Finland, he’s one of the greatest from all of the 20th century for me. But he never reached a wider audience. So, poets as bards, as performers, should travel and change the world, bit by bit. Poems, for sure, will travel themselves.

When writing your parts of “Dance of Life”, did you ever consider Freud’s concept of a “death drive” and a “live drive”?

No, not really. It was altogether a pre-Freudian concept brought alive. Also, maybe I understood Freud wrong in university but to me he seems to set us free… from being good. All “kind-hearted” is a super-ego thing, a learned way to cope, as all the urges, all dirty and eager to feed on others come naturally from the depths of the mind. I don’t see it, I don’t believe in it. But in me you can’t really find an intellectual partner to discuss Freud. I’ve always been interested in other ways to describe the beautiful human mind. Although I have read him and found some parts of it genius. But, back to your question, our poem simply seeks answers and a cure to loneliness, a map of darkened paths on which we are afraid to walk otherwise. I don’t know if we managed to create such a map-system, but at least I was hoping we would, somewhere in the process. Maybe it means something also that Estonian readers voted it (the much longer version than the CD) the best poetry book of last year.

The CD version of Dance of Life will be available throughout the world from Amazon UK on 3 February.

I

Cover photo: Doris Kareva and Jürgen Rooste presenting Dance of Life at the Estonian Embassy in London (Kaido Vainomaa).