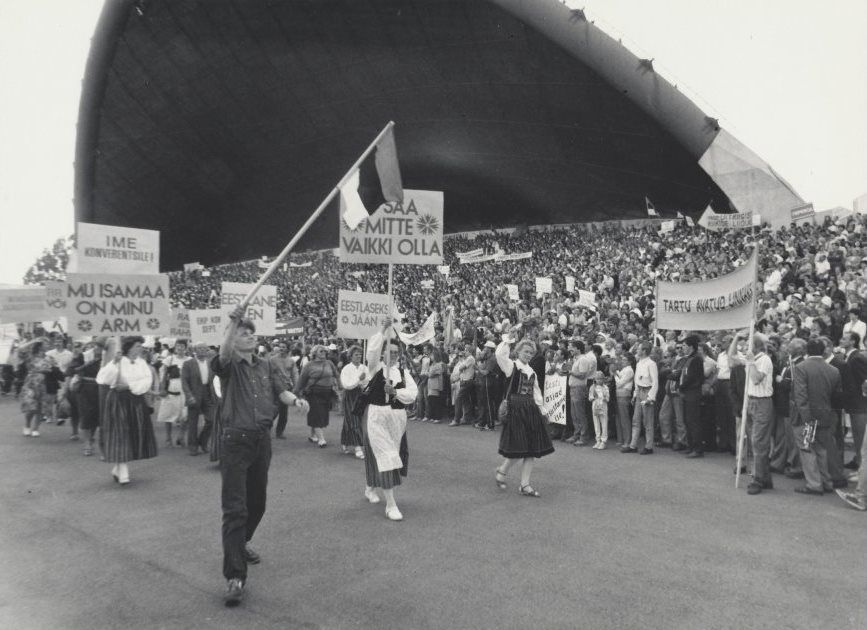

Estonia’s path to freedom began with mass singing at the Tallinn Song Festival Grounds in the summer of 1988; following the pivotal events of the Singing Revolution, Estonia’s journey to independence gained swift momentum.

On 11 September 1988, the Tallinn Song Festival Grounds witnessed what was arguably the largest mass gathering in the Estonian capital’s history. An estimated 300,000 people from across the country came together in a show of unprecedented national solidarity, a unity that had not been seen before.

This event marked another significant milestone in the peaceful independence movement, which had begun a year earlier in response to the Soviet government’s plans to excavate phosphorite in Estonia’s Lääne-Viru county.

With Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev allowing more press freedom, some Estonian journalists bravely informed the public about the potential environmental catastrophe of the phosphorite excavation. The Estonian national television’s environmental programme, “Panda,” first revealed this truth in February 1987, when host Juhan Aare interviewed a Soviet official in Moscow, who announced plans to begin mining in Estonia by 1997.

The revelation sparked a public environmental campaign against the excavation, eventually leading the Soviet authorities to withdraw their plans. During this campaign, in May 1987, prominent figures in the Estonian pop and rock music scene came together to record “Ei ole üksi ükski maa” (“No Country is Alone”).

Written by Alo Mattiisen and Jüri Leesment, this song became a significant prelude to the five key Singing Revolution songs Mattiisen would compose the following year.

Encouraged by a more liberal atmosphere in society, the Estonian Group on Publication of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was founded in August 1987. They organised a mass meeting in Hirvepark, Tallinn, demanding the public release of the 1939 pact’s secret protocol.

This meeting, unlike previous events, was not forcefully disbanded, indicating expanded civil rights and a softened Soviet regime. The authorities even permitted the demonstration.

As political freedom grew, Estonians began calling for economic reforms and the right to self-determination. In autumn 1987, the idea of a self-managing Estonia (Estonian acronym IME), proposed by Siim Kallas, Edgar Savisaar, Mikk Titma and Tiit Made, sparked enthusiastic discussion. The plan aimed to make Estonia economically independent from the Soviet Union, introducing a market economy and establishing its own currency and tax system.

In 1988, Estonian society became politically active en masse. A joint meeting of creative unions, including writers, artists, architects, and film and theatre professionals, expressed dissatisfaction with the Soviet Estonian leadership, headed by the Russian-born and Russian-speaking Karl Vaino.

In mid-April, the Estonian Popular Front was established. Proposed by the head of department of the communist-ruled National Planning Committee, Edgar Savisaar, during a live Estonian Television programme, the movement sought to democratise the Soviet Union and secure political and economic autonomy for Estonia.

The Popular Front quickly became a powerful mass organisation and was one of the main organisers of the significant concerts that year.

The term “Singing Revolution” was coined by Estonian activist and artist Heinz Valk in an article published a week after the spontaneous mass night-singing demonstrations at the Tallinn Song Festival Grounds on 10-11 June 1988.

In May, Alo Mattiisen’s “five patriotic songs,” performed by popular singer, Ivo Linna, premiered at the Tartu Pop Festival. These songs became the emotional backbone of the independence movement, featured in all major open-air concerts that summer, including the inaugural Rock Summer festival, the first of its kind in the Soviet Union.

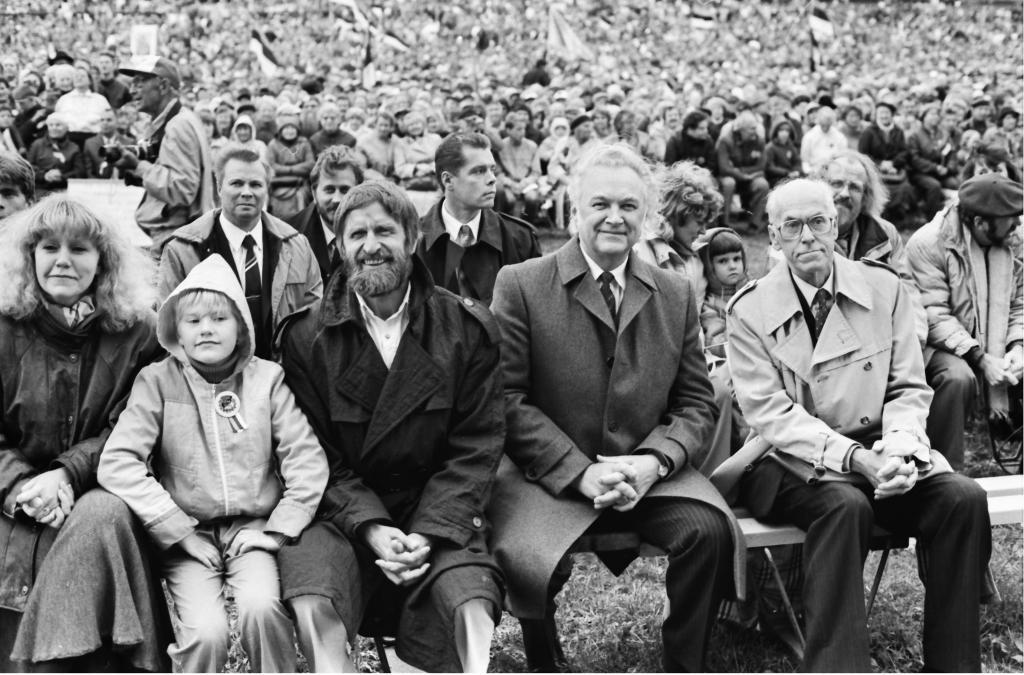

The sentiment of the Singing Revolution reached its zenith at the Eestimaa Laul (Estonia’s Song) concert on 11 September at the Tallinn Song Festival Grounds. With an estimated 300,000 attendees – though the exact number remains debated – this free event was a profound demonstration of national unity. At that time, Estonia’s total population was approximately 1.5 million.

The stirring speeches by independence movement figures such as Heinz Valk, Rein Järlik, Siim Kallas, Edgar Savisaar, Rein Veidemann, Mikk Mikiver and Trivimi Velliste stirred excitement and heightened emotions. Velliste, then chairman of the Estonian Heritage Society, was the first to express the ambition of regaining Estonian independence from the Soviet Union.

Valk, in his speech, famously declared what would become the most renowned slogan of the Estonian independence movement: “One day, no matter what, we will win!” (“Ükskord me võidame niikuinii!“ in Estonian), encapsulating the enduring struggle for independence.

The aftermath

After the summer of 1988, Estonia experienced significant and transformative events leading up to its restoration of independence.

1988

November: The Estonian Supreme Soviet, dominated by pro-independence factions, adopted the “Estonian Sovereignty Declaration” which asserted Estonia’s sovereignty and called for the gradual restoration of its independence.

1989

The Estonian Popular Front and other pro-independence groups continued to gain momentum. A massive demonstration, known as the “Baltic Way,” took place on 23 August 1989, where over 2 million people from Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania formed a human chain stretching from Tallinn to Vilnius to mark the 50th anniversary of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and show their desire for independence.

1990

March: Estonia held its first free elections since the Soviet occupation. The newly elected Estonian Supreme Soviet included a majority of pro-independence deputies.

May: The Estonian Supreme Soviet declared the sovereignty of Estonia, which included the right to determine its own economic and political systems.

1991

January: The Soviet Union attempted a violent crackdown on independence movements in the Baltic states. In Estonia, this led to increased tensions but did not result in significant violence.

August: The failed coup attempt in Moscow by hardline Soviet elements accelerated the push for independence across the Soviet republics. On 20 August 1991, Estonia declared its restoration of independence from the Soviet Union.

September: The Soviet Union officially recognised Estonia’s independence. Estonia was admitted to the United Nations on 17 September 1991.

1992

March: Estonia adopted a new constitution, which laid the groundwork for its democratic governance and market economy.

June: Estonia held its first post-independence parliamentary elections, leading to the establishment of a new government that focused on economic reforms and integration with Western institutions.

1994

August: The last Soviet troops withdrew from Estonia, completing the withdrawal of Soviet military presence from the country.

1997

Estonia signed an association agreement with the European Union, paving the way for future membership.

1998

Estonia formally joined the Partnership for Peace, a NATO program aimed at building relationships with NATO member countries.

2004

March: Estonia became a member of NATO.

May: Estonia joined the European Union, solidifying its place in the European community.

These events marked Estonia’s transition from Soviet occupation to a fully independent and sovereign state, integrating into European and international frameworks and establishing itself as a democratic and market-oriented country.