An unprecedented street art festival Mextonia brings together Mexican, Estonian and other international artists for one purpose: to create the most remarkable gift for Estonia’s upcoming centennial.

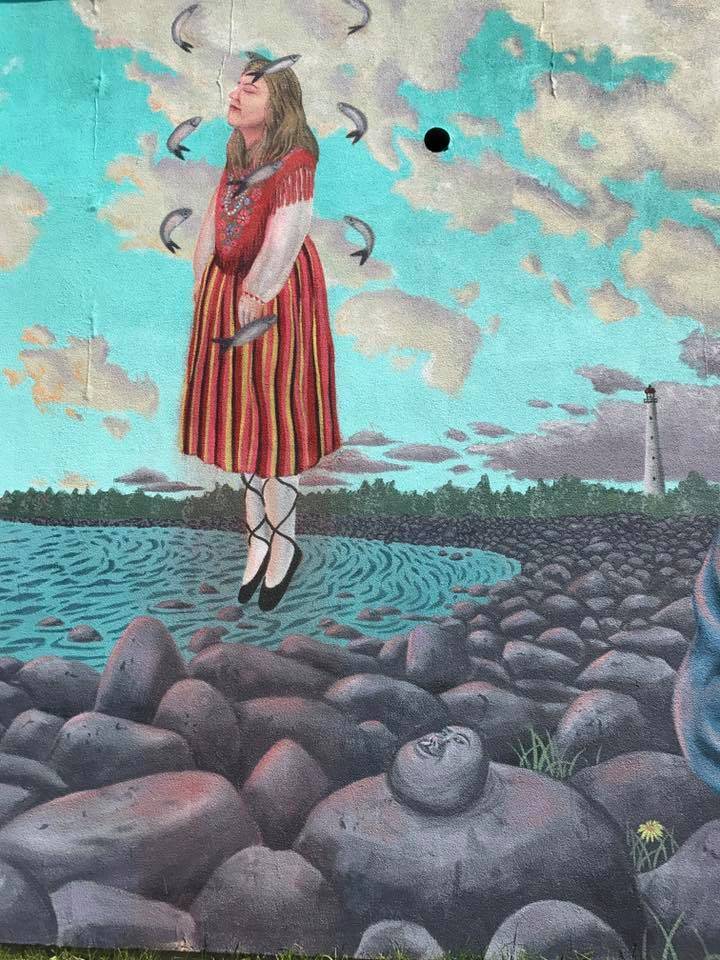

Before New Zealand artist Aaron Glasson arrived in Estonia this summer, he knew next to nothing about the country. Yet what remains of his visit is a colossal mural of Kihnu Virve, one of Estonia’s most well-known living folk singers, and two other women from the Kihnu island celebrating summer solstice by burning a boat and levitating, in Glasson’s words, “within a double helix of herring”.

His choice of topic for the work, now towering over Tallinn’s landmark art museum KUMU, was by no means accidental but stems from a wider appreciation of Kihnu’s culture and the existential threat the island now faces: “Like countless other island societies, Kihnu is intertwined with the sea and dependent on a healthy marine eco-system for its survival.”

But unusual as it is, Glasson’s encounter with Estonia is not unique.

In fact, he is just one of a whopping 72 artists and producers from all across Estonia, Mexico and elsewhere who took part in Mextonia, a transgraffiti festival that engulfed the streets of Tallinn and other smaller cities in June 2017.

The result? Over 30 colossal murals inspired by Estonia’s deep cultural roots and rich folklore, dotted around Tallinn’s highways and the seafront, as well as countless apartment blocks and municipal buildings in the capital and beyond. More than 5,000 square metres (54,000 sq ft) of wall space was transformed.

Mextonia, a joint effort by Nueve Arte Urbano and Todoesuno Eesti, is one of the most tangible and colourful “gifts” made as part of Estonia 100. It is perhaps also the most enduring one. Although the country’s centenary celebrations nominally begin next year, citizens and organisations have already started putting on a plethora of events and initiatives to celebrate – from giving Estonia’s music schools hundreds of new instruments, to gifting communities with ping pong tables painted by local artists. Mextonia’s inclusive, international character takes it one step further and shows how far the country has come in global recognition, with people even from the other side of the world joining in for its centennial.

Birth of an idea

While the gift gives Estonia a welcome and hopefully lasting injection of colour, what it truly stands out for is the cross-cultural process that went into hosting it.

As the festival’s lead organiser Edgar Sanchez from Nueve Arte Urbano says, “The main gift is a new cultural process that […] connects with all societal forces to promote a creative dialogue about the past and future of the Estonian culture and the social fabric of its cities.”

The idea for a street art festival that combines Estonian and Mexican cultures came about as a happy meeting of circumstances.

Sanchez visited Estonia and was struck by the country’s unique culture; Sigre Tompel, Mextonia’s lead organiser from the Estonian side, fell in love with Mexico’s vibrant transgraffiti scene during her travels there. Their mutual experiences happened to coincide with the upcoming centennial of the country, alongside another seminal event for the Baltic nation: for the first time since joining the EU in 2004, Estonia is at the helm of the Council of the EU from July to December 2017.

Add to that Estonia’s burgeoning street art scene that has blossomed as a new generation of artists, born and raised in post-Soviet Estonia, use the streets as their canvas for expressing and constructing a new cosmopolitan nationhood, and there you have all the ingredients for an unprecedented event like Mextonia.

Transgraffiti itself, describes Sanchez, is a matured form of graffiti where muralists have passed from the phase of scribbling names on walls to now “adding metaphors, transcending borders and involving themselves in cultural catalysis”. This is intrinsically linked to soft power in communities – transgraffiti muralists use their craft as a form of social influence to “become cultural leaders in the neighbourhood”.

Once the idea for the festival came together, the next step was to tap into Nueve Arte Urbano’s network of local artists and international allies. 26 of the artists and producers came from Mexico but other global organisations included US-based Pangea Seed and Sea Walls.

The enthusiastic uptake in Estonia was astounding: Stencibility from Tartu, Baltic Sessions from Tallinn, crews like Pirados and EKKM (the Estonian Museum of Contemporary Art) all played a role in getting the festival off the ground. Local authorities were consulted extensively and the paint used for the works was imported straight from Mexico.

Deconstructing Estonia’s cultural roots

But the job was never as simple as getting artists on board, handing them a couple spray cans and asking them to transform a public wall on the spot. What preceded was a lengthy curatorial process to sketch out the works and secure approval from property owners and local authorities.

Out of the international participants many had no previous connection with Estonia, not to mention knowing its cultural symbols.

Fernanda Arias, a Mexican artist and anthropologist who during the festival led the collective painting of an old tank near the Tallinn TV Tower with local children, describes the chance to explore a new culture from scratch as part of the appeal: “The possibility of not only getting to know, to contemplate or describe culture, but to actually forge it.”

And while local Estonian artists may have had a head start, depicting familiar characters and symbols anew, especially when they are revered and seemingly out of bounds for reinvention, is no easy task either.

To help sift through cultural symbols, the festival found a curatorial cornerstone in the Mextonia Manifesto, put together with the help of cultural academic Marju Kõivupuu, the Government Office of Estonia, as well as anthropologists from the Mexican team.

The result is a diverse reworking and mingling of cultural stories. While the subject matter and style of the works are diverse, all pieces by the international artists share a common thread in using an Estonian symbol as a starting point only to then flesh out a more universal narrative.

For Arias, the tank in front of the TV Tower – a historically significant spot where Estonia’s nonviolent fight for the restoration of independence in the early 1990s nearly tipped into brutality – morphed into a wider symbol of nonviolence that can be returned to Mexico “where we urgently need to re-signify many cultural symbols to finally achieve peace”.

A similarly symbiotic mindset guided Luis Sanchez’s choice to paint the head of an eagle by the Tallinn seafront. The eagle is a central mythological figure in Estonian folklore, having carried Kalev on its back to Estonia so he could become the country’s first king, but the bird is also one of Mexico’s cultural emblems, even appearing on its flag.

Mextonia also had a perhaps less tangible but just as important impact on the Estonian artists who took part. While challenging and reframing whatever we choose to call “Estonian culture” is nothing new for them, several local artists found that the unique international element of the festival enhanced their work. Sänk, a Võru-based artist who together with the group Original Skillz transformed a utility building next to the Tallinn Coach Station, noted that this was what made them “base ourselves on local sources as much as possible and do something really Estonian, but with a touch of Mexican vivacity and boldness”.

Indeed, there is a notable element of unpicking national archetypes in these works. Tartu artist Bach Babach, who has been active on the local street art scene since the 1990s, painted the hero of Estonia’s national epic, Kalevipoeg, near Tallinn’s port as a homage to the modern-day Kalevipoeg figures, a term used to refer to the many Estonian men who cross the Baltic Sea every week to take up construction and other lower-skill jobs in Finland where salaries are still higher than on this side of the pond. Cleverly making use of the life-saving equipment already on the wall, a Seto girl who has moved to the capital from her native southern Estonia stands by to watch over Tallinners and throw a lifebuoy to anyone in trouble.

While the connection to Mexico and other cultures does not feed into the artwork in any obvious way, Bach Babach did commend the “positive influence” of the festival’s international team, opening up an “international bridge straight to Mexico on a personal, artistic level”.

A Herculean effort in planning

It cannot be understated just how much logistical muscle the project required before transforming the urbanscape in this way.

The process from inception to creating the works took over a year. Sigre Tompel outlined the mammoth task the organising team had to undertake: first to get initial permission from local authorities, then to find and liaise with 100 wall owners, then review sketches by 60 artists, and finally run them by local authorities and make any necessary amends with the least infringement on the artists’ original concept.

Estonian weather, too, tried its hardest to become the star of the show. Creating the works could take days as the weather oscillated between rain, biting cold and bouts of sunshine. There is a poetic element to how Luis Sanchez describes working for three days solid during the longest days of the year as the landscape “fluctuated from stark and uncomfortable into beautifully mellow and awe-inspiring sunsets at the dock, as the days went by almost endlessly in the Estonian summer”.

Being battered by, and overcoming, extreme conditions did not end there. Bach Babach had no option but to get used to working underneath a speaker using noise to deter seagulls, while Neki, a Tallinn-based artist whose canvas became an apartment block on one of Tallinn’s busiest roads, recalled how a strong gust of wind hurled a pot of paint from the fifth floor straight onto a neighbour’s Mercedes.

Neki’s is perhaps the most intense story of them all and perfectly epitomises the festival. Painting through several floors and only able to focus on one detail at a time, the artist had no option to see the full work from the distance – bar occasionally nipping into the hallway of the building opposite to take a picture.

Welcomed with barbeques

When you speak to anyone involved in Mextonia, the resounding final message is one of unity and cross-cultural exchange. Nowhere is that more evident than in Aaron Glasson’s anecdote about when he finally came to finish his mural. Over the several days it took, he had made friends with many people from the neighbourhood. One young family living nearby stood out in particular – so, once he had finished, he went over to their house for a BBQ.

This is indicative of the warm reception the murals have had all round.

Tompel tells of residents of large apartment buildings coming together to thank the artists and give them gifts in return. Several of the wall spaces also belong to corporations, something Tompel finds particularly remarkable: “Such approval and recognition shows adaptability and openness to new things, even though everything new seems doubly scary at first.” And the murals continue to yield a treasure trove of positive responses on social media.

It is still too early to tell how much Mextonia has contributed to the street art scene in Estonia at large. As Estonia’s precious cultural icons become deconstructed and given new life through the fabric of its streets, the immediate end result has been a perfect convergence of the local with the international, the aesthetically pleasing with the culturally resonant.

But perhaps more importantly, it has given a confidence boost to the country’s burgeoning street art scene. Bach Babach reads the festival as a part of the general direction Estonia’s street art is taking: “I think that the overall movement of Estonian street art is also towards more substantial, thoughtful and large-scale forms. Mextonia has definitely played a positive role in this.”

Glasson concurs, seeing no end to the potential: “There’s a lot of really talented artists in Estonia and plenty of great empty walls.”

You can find out more about Mextonia from the festival’s Facebook page and the official video. A short video about Aaron Glasson’s visit to Kihnu Island in preparation for his mural is available here.

I

Cover: Artwork by Aaron Glasson. Producer: Nueve Arte Urbano