Rael Kõiv, a Tallinn and London-based Estonian musician and composer, talked to Estonian World about her new album, “Return to Natural Law”, and her career in Estonia and the UK.

Rael Kōiv is an Estonian-born composer and pianist, who has lived and worked in the UK for the past few years. She studied music composition at the Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre, and in England, at the University for the Creative Arts. Her compositions can vary from solo piano to string quartet or expand to extensive orchestral scores merged with sounds from nature.

Rael, you just released a new album, “Return to Natural Law”. What experience and thoughts do you hope people will take away from listening to your new album and your music in general?

“Return to Natural Law” is my second self-released album, and it expands my musical expression in numerous ways. The album was recorded in Estonia and the UK. The music is all instrumental, featuring my original compositions for piano, strings and sinfonietta orchestra. In terms of the sound, I would say it has a romantic, cinematic feel to it.

From my perspective, it is a musical journey and introspection to comprehend our oneness with nature and return to living in harmony with her laws, creating a more balanced world in and around us. I write what’s in my heart. I hope it will get to people and touch or inspire them somehow.

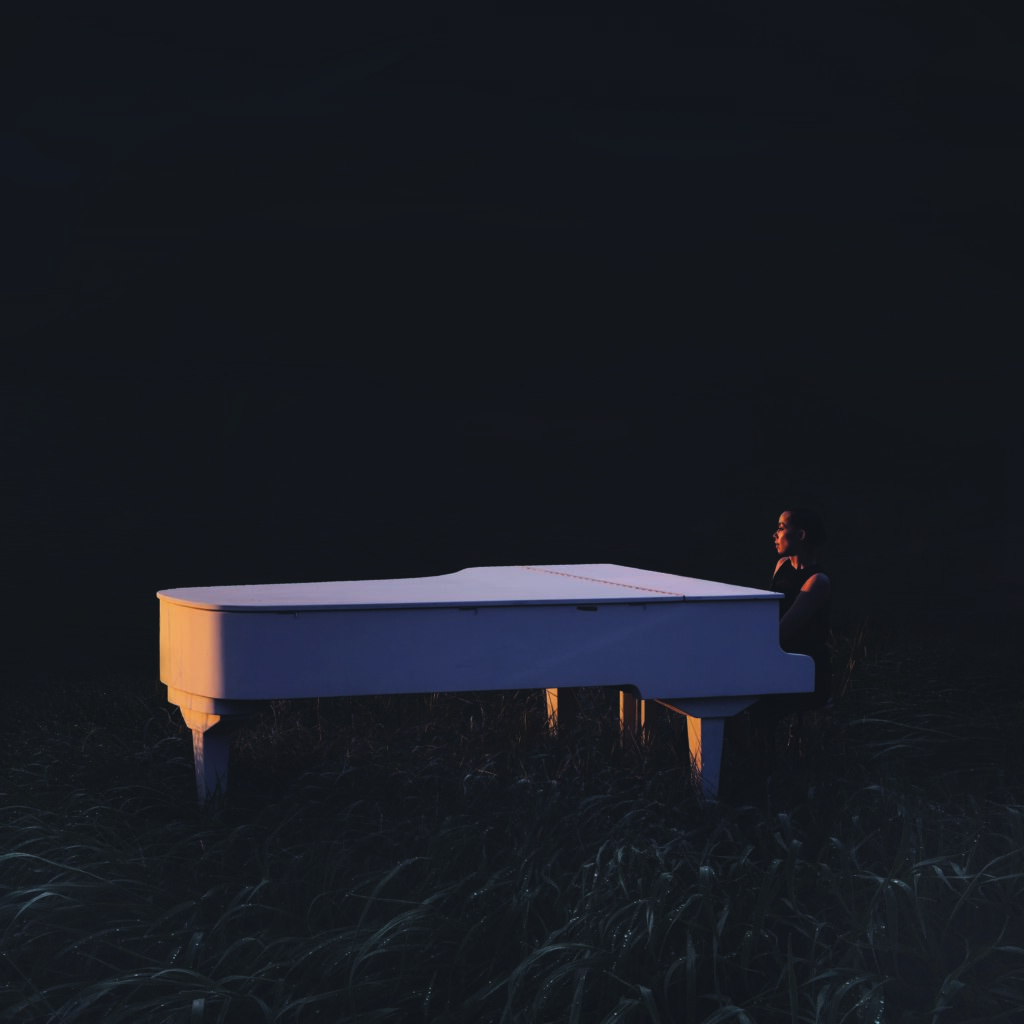

Kylli Sparre, an amazingly talented photography artist, created the most beautiful visual representation of the music for this album.

Nature and music appear to be deeply connected for you as a composer. Your work reminds me of Yann Tiersen who is from Brittany on the Atlantic coast of Europe.

Both nature and music create a space for me, where I can deeply connect with my soul. Both purify and keep me “in tune” in this world.

On my first album, I collected sound recordings of waves in the sea and mixed them into my piano recordings. On the new album, you can also hear the sounds of cranes recorded by Fred Jüssi, who kindly encouraged me to use them in my piece “We Dance for the Joy”. In the future, I’d love to incorporate more sounds from nature into my compositions and live performances.

Is composing music a search for a meaning – does music help you perceive the world around you?

Estonian composer Arvo Pärt has expressed it beautifully: “A composer is a musical instrument and at the same time a performer on that instrument. The instrument has to be in order to produce sound. One must start with that – not with the music.”

I would add that creating music is a process that keeps me connected to my core being and gives me access to the non-physical spheres of this world.

How do you go about composing new music? What do you start with? Is it like work – you set aside time and space to do it – or does it just start to happen when you are doing normal everyday things?

I take time and give myself space to sit down behind the piano with a piece of paper and a pencil. I truly enjoy composing this way. I sometimes feel an urge to immediately find time with the piano while doing everyday things, but I don’t start composing a new piece inside my head while doing other activities. I have to carefully create the space and dedicate my time and full attention to tuning into what comes up for me musically.

What were your early passions and influences? Was there someone or something that inspired you initially?

I started playing the piano in a music school when I was eight years old. I didn’t have anyone from my family pushing me to make that decision. It was simply something my heart desired.

I wrote my first piece of music when I was 12. I remember there was a specific event which opened my mind about writing my own music. It was a piano ensemble festival held in my music school, where there was a guest composer, Ardo Ran Varres, present. Some of his compositions were being performed there.

I remember how moved I was when listening to his piece for a stage play “Dinner with Friends”. I had never felt the same kind of connection with music written by composers who had passed away decades or rather centuries ago. I didn’t feel the same connection to them or their musical language. Since then, I discovered the joy of writing and performing my own music.

How do you see yourself evolving as a musician?

I’ve grown into trusting my voice as a composer and musician. I also feel I’m more open to experimenting with new ideas and taking risks, accepting failure simply as part of the evolving process. The path has been with plenty of ups and downs, but I’m constantly learning how to ride those waves without favouring one over the other.

I’ve also experienced that often the best way to get where you need to be, isn’t the easiest or the most obvious one. For example, it had always been my dream to get accepted to the Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre, but when I started my studies there, I realised it wasn’t for me.

After more than a four-year gap in composing music, I started writing “Sacred Dreams” (my debut album), where I dedicated myself to rebuilding my connection with music. It was never lost, simply in the process of transformation. This led me to the UK where I studied music composition and technology for three years at the University for the Creative Arts. It turned out to be one of the best decisions I’ve ever made in my life.

Do you feel that living in London has had an impact on your music and on your new album in particular? And what about Estonian nature?

My surrounding environment has an impact on the music I write, for sure. More than affecting the musical expression directly, it has to do with how I feel and sense myself in that particular place. How free can I be in my mind directly impacts how freely I can express myself via music. For example, when I was living in the UK, I felt more freedom than I’ve ever felt. I felt supported. These aspects encouraged me to take greater risks and think and dream bigger, one of the results which you can see and hear now in the form of my second album.

But I also feel the need to come to Estonian nature – to reflect and purify my soul from the experiences I’ve gone through and to release the old and get new impulses for my next creative projects. And I carry Estonian nature with me wherever I go. It is present in ways I’m communicating with people and the environment around me, in the music I create and in projects I choose to invest my energy in.

I started to write the album in Estonia and all the piano parts were recorded at Peeter Salmela studio in Tallinn. However, most of the music on the album is written and recorded in England, while I was doing my degree there.

But the album photos were taken in Estonia. Regarding nature, there’s no other place like here in the world. For the photoshoot, we took a grand piano to the coast. We had eight men carrying it to the location. I wasn’t sure if we could actually manage to make it happen until it was done. But I couldn’t imagine the album art in any other way. To play by the sea feels like the most natural setting for me. The piano was out of tune, the pedals were stuck in the grass, and the weather was cold, but it didn’t matter in the slightest. The synergy between me and the photographer, Kylli Sparre, made it all irrelevant.

How would you compare the creative scenes in Estonia and in the UK and how does it impact your own work?

I’ve been away from Estonia for more than three years, so my take on that might be a bit outdated, but in my view, here in Estonia, there isn’t as much support for young creatives as there is in the UK – especially, when your path isn’t as straightforward as the society expects.

In the UK, they have a culture of supporting young talent. For example, they have organisations like Help Musicians where, in addition to financial support, you can ask for advice on your career. If you are having a bad day and need someone to talk to, you can also just call them for mental support.

I also felt more appreciated and valued in the UK as a musician. Partly because there are more job opportunities, plenty of collaborations you can apply to become part of, and the salary is in accordance with the work you put into a project. When you feel supported in a culture, you are more willing to take risks and you feel empowered to become involved in more ambitious projects. My second album is an example of that.

Having said that, I am always impressed by how many talented hard-working creative people we have in Estonia. Whenever I have introduced some Estonian visual artists or musicians to people in England, they are absolutely amazed by the professionalism and high quality of the work. In Estonia, there are many things we could do to support them better.

Can an album itself be considered a form of art, separately from the individual works on it? I understand you produce our own albums but if you were with a large record company they would have more influence – is that a trade-off worth making?

I grew up in a time when listening to the artist’s whole album as a piece of coherent work was a common way of listening to music. In my experience, this way of listening takes you closer to the artist’s mind space and you get absorbed into the world that has been created. It’s a very special journey, I believe. I see and sense an album as a book – no chapter can be taken out of it without affecting the whole piece of work. I think a lot of that magic has been lost these days with streaming services being the primary way of consuming music for people.

A physical CD and its artwork are telling a visual story of the album next to a musical one. It unveils the titles behind the compositions, giving you a deeper experience of the work. For example, with my latest album, one can find Kylli Sparre’s magical photographs inside the CD’s booklet – as well as couple of poems written by my dear friend, Maria Kesa, whose poetry has inspired me over the years.

I agree that being with a large record company would have more influence and bring more listeners to my music. So far, I haven’t found a label that would resonate with what I’m creating yet. I have heard that many independent labels give a lot of freedom to the artist and there’s no trade-off needed to be made in terms of the content and music the artist desires to make. I imagine it’s not the case with large record companies, though. I release music with a certain vision and intention that I need to communicate to the world. If I would have to compromise on that, it would become a business deal, not an original creation. I’m not saying it is a bad thing, but it should be named for what it is.

You have also composed music for art exhibits.

Yes, I have been fortunate to collaborate with some of the most inspiring and talented visual artists in Estonia. Thanks to the most imaginative art curator I’ve ever met, Meelis Tammemägi, I have performed at the exhibition opening events for visual artists, such as Mari Roosvalt, Laurentsius and others.

The most recent project was a collaboration with visual artist Jaanika Peerna, photographer Kaupo Kikkas and Meelis Tammemägi. We took a grand piano to the Pōhjala Factory space in Tallinn and placed four empty canvases around the piano. The performance was born as an improvisation between my piano playing and Peerna painting on the spot. We met for the first time with Jaanika on that day and had no idea what was going to happen. We connected immediately and the result was beautiful.

In my experience, if there’s a true connection between a piece of art and music being performed in the same space, it has the potential to create an environment where the audience feels more open to receiving both, the visual and auditory, impulses.

I’m currently creating a sound installation in collaboration with sound artist James Wright aka Bananafish for an upcoming street art exhibition “SAH” (Street Art History), curated by Meelis Tammemägi, at the Solaris centre in Tallinn.

Does music mirror society or help lead it forward by inspiring and uplifting?

I think we have forgotten the true potential of music these days. For example, to the ancient Chinese, the wave of sound was a living entity, constantly shaping the universe as a river shapes the surrounding earth. The wave represented the creative powers of qi, the ability of energy to give shape to form. Their musical scale was the spiritual basis for the whole of civilization. I feel like nowadays we have lost some of that wisdom and appreciation towards music that the ancient nations possessed.

Do you have any dream projects you would love to make happen one day?

My plans are ambitious. Usually, I don’t talk about specific projects I have in mind before they get realised. If I did, I would give away a lot of the energy I need to put into the creation itself.

But I’d love to create performances on a much larger scale than I’ve done so far – including an orchestra, visuals and nature soundscapes. To get the audience closer to what I’m feeling when I’m writing, playing and imagining my compositions. Next to my solo career, I’d love to score music for films and collaborating more with inspiring people in other creative areas.

If all goes well, my plan is to support other emerging talent in the industry by setting up a funding platform. I’d like to give them an opportunity to fully commit to their creative practices on an everyday basis.

Another contribution that I’d like to make is to use some of my income to help restore the natural ecosystems of our beautiful planet. It would be the least I could do – to express my gratitude for it.

Rael Kõiv’s album “Return to Natural Law” is available on CD and digital download directly from her website or her Bandcamp page. The CD album is also available at Lasering online shop and Apollo stores in Estonia. Rael Kõiv’s music is digitally available on Spotify, Tidal, Apple Music and Soundcloud.