Experts often laud the pedagogical freedom of Estonia’s education system and many of its teachers agree. However, as with any system that seeks to disrupt the traditional order, there are bound to be a few obstacles.

This article is published in collaboration with Education Estonia.

One of the key characteristics of the Estonian education system is the autonomy granted to schools and teachers. There is a framework for curricula that stipulates learning outcomes by school level, however, how those outcomes are reached is ultimately decided by the individual institutions themselves. What’s more, each school level also decides the evaluation system and study material that is used, as well as how the learning process is organised – whether it be project-based, thematic or traditional subject-based learning.

While speaking about teacher autonomy, Eve Eisenschmidt, professor of educational leadership at Tallinn University cites motivation theory, explaining that “If a person has a choice, then this person is more interested and therefore ready to experiment with new methods and to be more responsible for developing their teaching practices.”

Likewise, teaching development manager at Avatud Kool (Open School), Iiris Oosalu notes that if the education system’s goal is to raise self-sufficient citizens – as it is in Estonia – then fostering a holistic environment in which faculty also have the opportunity to direct their pedagogy is crucial.

It’s worth noting that the OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) shows that teacher autonomy is an important factor in promoting experimentation in the classroom. In Estonia, 93 percent of teachers report having control over determining course content in their class, compared to 84 percent on average across the OECD countries and economies participating in TALIS.

Eisenschmidt traces the resolutions that resulted in greater autonomy back to the 1990s. She explains that at the time, the overarching principle was that decisions should be made where they will ultimately be implemented.

“It starts from the school level: the school chooses, decides and creates an environment for learning and teaching. The teacher decides how to reach the goals, choosing methods and evaluating processes – there aren’t any obligatory learning materials,” explains Eisenschmidt.

Flexibility begets better outcomes

Avatud Kool, a small private school in Tallinn, is combining two-way immersion and project learning methods in its work. Oosalu says that autonomy can not only make her school but also those around the world significantly more flexible, allowing schools and teachers to meet their students’ individual needs. Similarly, she notes that autonomy, flexibility and self-directed personnel make unique situations easier to handle.

“For example, in March 2020 we had one and a half days to switch to distance learning. We made a crisis team and thought about what the main needs for our students, families and school are, and we did well in this situation,” she explains.

More specifically, the TALIS survey reflects opportunities for teachers to have a voice in developing school vision and goals, both of which are an integral part of teacher leadership. In Estonia, for example, 83 percent of principals report that their teachers bear significant responsibility for the majority of tasks related to school policies, curriculum and instruction, which is higher than the OECD average of 42 percent.

Oosalu adds that this means teachers and the school take on a collaborative leadership role, working together to decide how exactly the learning outcome set by the state should be reached.

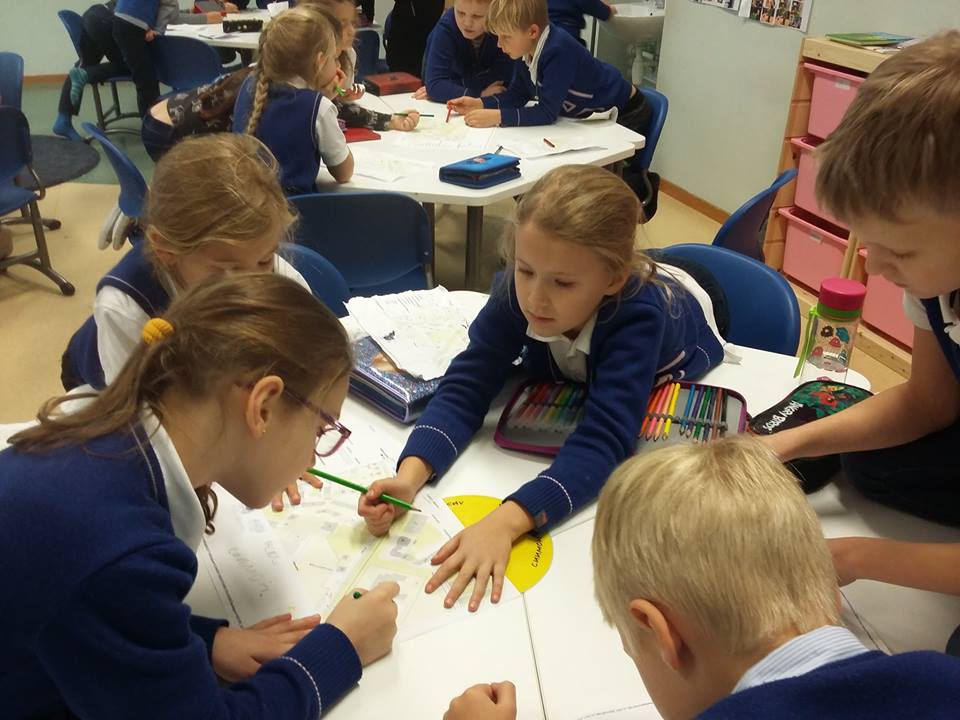

For instance, at Avatud Kool students take general subjects such as maths and languages, however, other subjects are taught through a more hands-on, project-based learning approach.

Recently, they hosted a five-week project that combined biology and the humanities. Oosalu explains that pupils studied various animals both in the classroom and during fieldwork at local shelters. The project culminated in a student-led charity fair in support of the shelter.

“They did it all by themselves – visited an animal shelter, analysed what kind of care the animals in the shelter needed, organised the fair, calculated the budget”, Oosalu says, adding that through project-based learning, the most important factors are to have clearly stated learning outcomes, pose poignant questions and present a final project to the public.

More connections between subjects

One of the many teachers who speaks highly of this more autonomous education system is Joana Jõgela, a chemistry teacher at St Peter’s Lutheran School and Hugo Treffner Gymnasium in Tartu.

“My eighth grade is learning reaction equations via virtual reality. Chemistry is dealing with the world invisible to the eye. For example, what happens with salt in water – how does it decompose into ions? Well, of course, it is possible to pour two transparent liquids, but it is not so attractive. Virtual reality makes the abstract ions more real for pupils,” she explains. The solution for virtual reality lessons was developed by an Estonian edtech company, Futuclass.

“There is no required method in curricula, I can choose which is best for me and my students. I am totally using my freedom and only my own creativity puts limits,” says Jõgela.

Incidentally, Jõgela favors a method of instruction known as “flipped classroom”. “It is a good method because students don’t have to just listen, but they actually need to be actively involved, they need to learn. I think it raises their curiosity and joy of discovery,” she says, explaining how they engage in teamwork, use resources in the lab and even play board games. However, Jõgela admits that while some students are enthusiastic about non-traditional learning styles, others take a bit longer to fully engage with it.

According to Jõgela, one way to improve the situation and better meet students where they are at would be through integrating different subjects, something she picked up from a school in Lithuania. “I saw some classes where chemistry and geography were integrated while teaching about natural resources. Students ascertain rocks via chemical reactions and analysed their content. After that they saw the information about analysis made by machines and calculated the content of different substances in the rocks,” she explains.

Support system needs work

Jõgela also admits that although greater autonomy allows every teacher to choose their focus, it is imperative that they can also teach general knowledge alongside specific subjects.

Meanwhile, Eisenschmidt and Oosalu believe that although its value is significant, such levels of autonomy can also be overwhelming due to a lack of support and the fact that developing new school-level curricula and lesson plans require a lot of additional working hours. Oosalu says that it can be especially difficult for teachers starting their careers.

Luckily, however, she notes that there is work currently being done to help these instructors ease into their new roles while at the same time keeping the passion of more seasoned and veteran teachers alive.

Despite the many upsides to an autonomous learning environment, Oosalu and Jõgela still raise the question: if every school and every teacher is operating with such freedom of choice and such wildly different motivations, can there be any uniform criteria for the quality of instruction?

In response, Eisenschmidt suggests that autonomy undoubtedly means diverse schools, a landscape in which some are actively pursuing experimental and creative methodologies while others remain firmly rooted in tradition. Given that reality, she explains that while there is no external evaluation – in fact, on a national level the ministry of education has no recourse to inspect schools – what is used are various benchmarks that schools are meant to hit while also conducting internal evaluations, as well as diagnostic tests for teachers to monitor students’ progress.

Oosalu sums it up as such: “The autonomy asks for greater responsibility, and this can be tiring, can even cause burnout. It takes a lot of energy but at the same time, it is greatly inspiring. If we can see that our work succeeds and students are happy to come to school, our work satisfaction increases. We are happy to put all this effort in.”