People in many large first world countries are having less children while Estonians are finding ways to halt their long fertility decline.

This article is published in collaboration with Research in Estonia.

When a group of young New York documentary makers came to Estonia to report about its digital society, they ended up wishing they could move to this small and dark Nordic country. Not because of Estonia’s e-governance solutions. Instead, they were more interested in having kids here.

In the queueless, seamless futuristic society where people can vote and do their taxes within minutes online, Estonia’s new upcoming success story may be something much more conventional – its family policy.

“Estonia is starting to get noticed in recent years,” Allan Puur, Estonia’s leading demography expert at the University of Tallinn, said.

Solving the crisis

Puur has been working with the parliamentary committee that deals with population issues. The committee – with a slightly dramatic name “The Study Committee to Solve the Demographic Crisis” – was formed in 2017 and has been closely cooperating with scientists and experts in the field.

Their goal is to make sure the Estonian nation, language and culture are preserved. In a country of only 1.3 million – it is a real challenge.

Luckily, Estonia has one of the best family policies in the world, as noted in a recent UN report.

For a year and a half, Estonian parents receive a fully paid parental leave, depending on their salary before getting pregnant, with a maximum of thrice the national average. At the same time, they are still allowed to earn extra if they wish to do so. Either parent can take the leave.

The job they had before the parental leave is kept for at least three years. If the mother has another child within three years, her benefits will continue to be the same. This provision tends to stimulate parents to have shorter birth intervals.

“The combination of relatively long leave and full replacement of previous salary in Estonia is even more generous than the leave systems in the Nordic countries, where the leave is either shorter or with full wage replacement,” the UN report concluded.

Understandably, in such a small country, every child counts. And you can sense it in Estonia’s maternity sections in public hospitals. They are almost magical places. There are baths, exercise balls and other equipment in many birthing rooms. Mothers can dim the lights and bring their own music to relax better. Each birth is marked on a public board in the corridor with pride. And all this, of course, is for free.

Population issues in focus during elections

Estonia’s new family policy kicked off in the same year as the country joined the European Union in 2004. Initially, the duration of leave was one year. In 2008, it was extended to 1.5 years.

And it paid off.

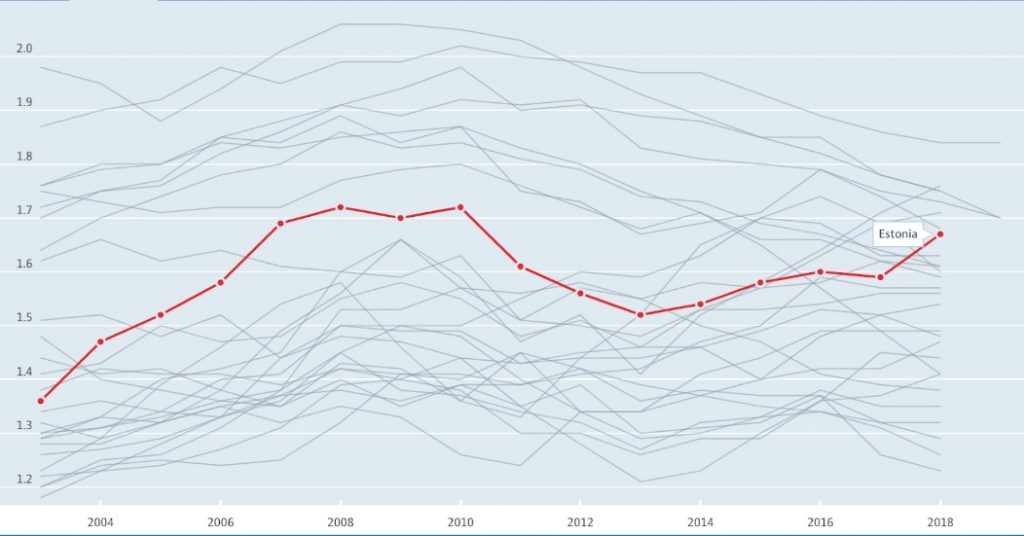

The total fertility rate jumped from 1.37 in 2003 to 1.72 in 2008. In other words, closer to two children per woman.

The positive impact of the parental leave scheme was clearly evident during the economic recession between 2009 and 2010 when, despite the upsurge of unemployment and deteriorated economic prospects, the fertility rate stayed at the level of 1.70–1.72.

Many women with one or two children made use of the generous parental leave to withdraw from the labour market, have another child and return to work later, when the peak of recession had passed, Puur explained.

In July 2017, another important family policy measure was introduced to encourage parents to have a third child by giving them additional benefits. During the next two years, the number of third births increased by more than 20% compared to the period before the measure.

Population experts say that whether fertility rates are relatively close to two births per woman or far below that level matters greatly, especially in countries where people tend to leave in great numbers. This was the case in Estonia after joining the European Union, although massive outmigration has stopped now.

Since 2015, Estonia has shown positive net migration.

How many children do Estonians have now?

To get a more realistic account of the fertility levels, demographers use cohort fertility rates instead of the total fertility rate which can be biased up or downwards depending on how the childbearing age changes, Puur explained. For Estonia, the cohort fertility rate shows that women, who are approaching 40 years of age, have had 1.80–1.85 children on average.

For native Estonians, the average number of children amounts to 1.90 (around a third of Estonia’s population are ethnic Russians and their descendants who have less children).

This means Estonia is slightly above the modern fertility target of 1.8 children per woman. If that rate is kept for a long period of time, it would lead to a moderate annual population decline of 0.4%, according to the UN report. In that case, the government would still be able to tackle it with adjustments in the labour market, pension systems, health care and social security. Or it could even be offset by accepting moderate levels of immigration.

By contrast, a long-term total fertility rate close to 1.0 would result in a population shrinking by 2.4% annually and drastic population ageing. Such a pace of decline would be challenging even for the governments accepting many immigrants or implementing radical reforms to their social security and pension systems, the UN report states.

Such extremely low birth rates are not just hypothetical. Birth rates in Malta, Spain and Italy are the lowest in the EU, below 1.3 children per woman. Outside the EU, similarly low fertility levels are also found in several East Asian countries like Hong Kong, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Singapore and Taiwan.

It is still early to say whether Estonia’s family policy will bring results that are sustained for a longer period and the total fertility rate will one day reach the dream number: 2.1 children per women on average.

So far, the measures have worked.

“Besides learning from the best practices of other countries, we have to experiment with new solutions on our own,” Puur said.

A hundred years of small families

Estonia has quite a unique history when it comes to its population.

Estonians started having less children during the national awakening in the second half of the 19th century. It was the time when the Russian tsar, Alexander II, gradually granted Estonian peasants the right to education, property and liberty to move within Estonia and abroad.

By the end of the century, 96% of Estonians were literate.

But the cribs now stay empty. By the turn of the 20th century, small families with around two children became the new norm.

It has been estimated that the “population explosion” that rapidly brought the world population from about 1.6 billion to six billion during the 20th century did not affect Estonia as much and only increased the number of people by 1.6 times. This was an extremely low growth compared with many other countries. In various developed countries, the increase was 15-20 times.

The 20th century was not kind to Estonia. The country was hit with world wars, the Nazi and Soviet occupations, deportations and an exodus to the West in 1944.

And, of course, it affected parents’ desire to bring babies into this world. In the 1950s and early 1960s, both Estonia and its neighbouring Latvia had one of the lowest fertility rates in the world.

In short, it is a miracle that Estonia still even exists. And it seems the small country is doing everything to keep it that way.

The cover photo is illustrative. Photo by Aron Urb.