The Association of Estonians in Sweden is celebrating its 60th anniversary, but the peoples from the two countries have been in contact for over a thousand years.

Estonia and Sweden share a long history together. Historical records show that first encounters between the two neighbours began in the early Middle Ages (500 AD – 1000 AD) and had a peaceful start. Swedish-speaking groups settled in Estonia – later known as coastal Swedes (rannarootslased in Estonian), probably migrating down from Finland. They lived on the islands and the west coast of Estonia, fishing, farming and trading across the Baltic Sea.

Around the turn of the millennium, however, the relations got rockier. In 1030, a Swedish Viking chief called Freygeirr may have been killed in a battle in Saaremaa. In the 12th century, chroniclers describe Estonian and Oeselian (Vikings from Estonia who lived in Saaremaa island) raids along the coasts of Sweden. One of the most notorious raids by Oeselian pirates occurred in 1187, when they attacked the Swedish town of Sigtuna – among the casualties was the Swedish archbishop Johannes.

Swedish rule

The Swedes, in turn, showed their strength centuries later, when, during the Livonian war in 1558, northern parts of modern-day Estonia became Swedish territory. Over 70 years later, the Polish-controlled southern parts were also conquered by Swedish forces and by 1645 the entire country was under their rule.

In Estonia, the time of Swedish rule is sometimes referred to as the “good old Swedish times” (vana hea Rootsi aeg). Historians are, however, divided whether the Estonian-speaking population used this expression at the time – or whether they considered the time of Swedish rule significantly better than that of earlier foreign rulers.

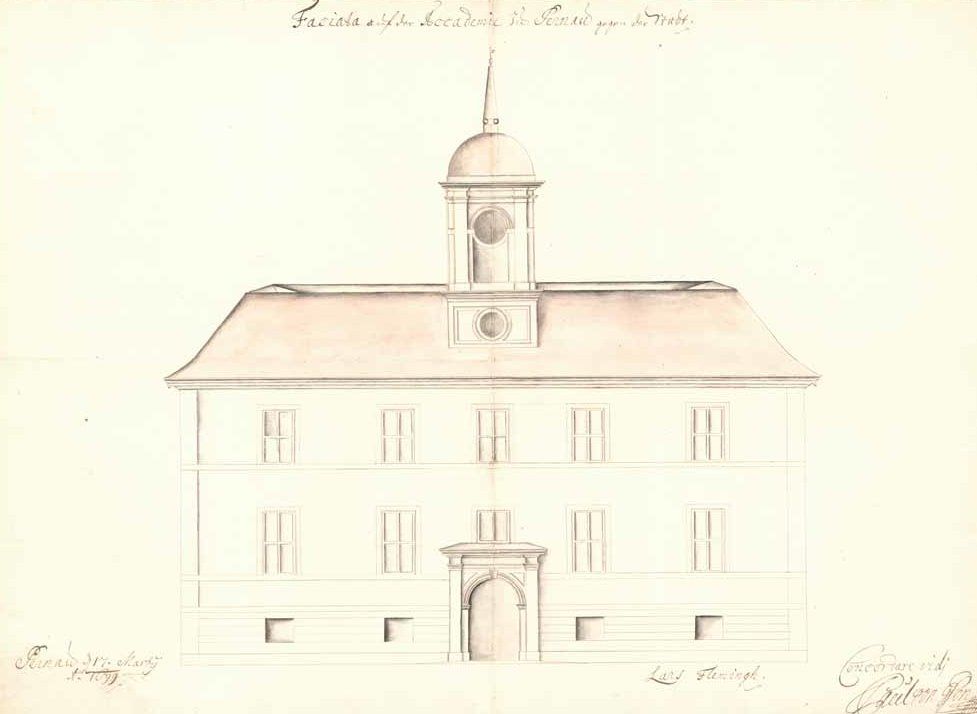

Swedish authorities did, however, enact a number of reforms that were aimed at lessening the influence of the local German-speaking aristocracy, to the benefit of the local Estonian-speaking peasantry. Swedes also established the University of Tartu and the Gustav Adolf Grammar School, and created a court of appeal in Tartu. Hence, there is some evidence to suggest that the native population considered Swedish rule as characterised by the rule of law, and it has been recorded that in later, harsh times the lower classes expressed a wish for a return to Swedish rule.

The rule came to an effective end in 1710, when all the Swedish Baltic provinces capitulated to Russian troops during the end-stages of the Great Northern War and Estonia came under Russian hegemony until 1918. Despite the harsh conditions under the tsarist Russian empire, the coastal Swedes, however, stayed put until the end of the Second World War. These days, their heritage is still clearly visible in the form of cute wooden architecture and churches in the Estonian islands of Ruhnu and Vormsi and Noarootsi peninsula.

Estonian boat refugees

Unlike the coastal Swedes, who lived in Estonia for centuries, the significant Estonian communities in Sweden were not established until the mid-20th century, when the history took a nasty turn.

Before the Second World War, only a few hundred Estonians lived in Sweden, but this number changed dramatically when, in the autumn of 1944, fearful of the advancing Soviet Red Army, approximately 70,000 Estonians left their country behind and escaped to Germany and Sweden. Some 30,000 were desperate to get onto any ship that stayed afloat, including tiny wooden fishing boats, making a journey of over 200 nautical miles (370 kilometres) to reach the Swedish shores.

Upon arrival, Estonians were accommodated in refugee camps. Reportedly, the integration of Estonian refugees into the local society happened more quickly in Sweden, compared to war-ravaged Germany where many had to stay in refugee camps until the late 1940s. However, the Soviet Union’s aggressive repatriation politics caused fear in many people that they might be forcefully returned to the Soviet-occupied Estonia, resulting by a number of Estonian refugees in Sweden move to the US, Canada and Australia instead.

Affluent Swedish Estonians

Regardless, by the late 1940s, the Estonian population in Sweden had expanded within short space of time from few hundred to about 20,000. The baby boomer years saw this figure rise to 30,000 by the 1960s. Some of the brightest Estonian minds, such as poets Marie Under and Gustav Suits, writers August Gailit and Karl Ristikivi, and architect Olev Siinmaa, settled in Sweden.

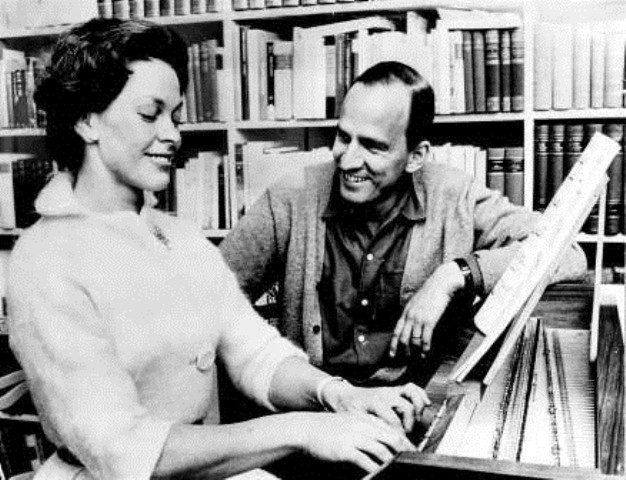

As in every country where the Estonians set their foot after the war, they successfully integrated into the Swedish community – some more affluent and fortunate than others. Probably the most famous one was Käbi Laretei, who had a long and distinguished career as a pianist, playing to packed halls not just in Sweden, but also in the UK, Germany and the US, including Carnegie Hall in New York. She was briefly married to Swedish most famous film director, Ingmar Bergman, introducing him to a variety of music along the way – some of which he would use in his film scores.

Ilon Wikland, an artist who is still going strong at the age of 87, had a long-time collaboration with the Swedish children’s writer, Astrid Lindgren, providing illustrations for some of her most distinguished books. Ilmar Reepalu became mayor of Malmö and during an almost 20-year long tenure oversaw the transformation of his city from an industrial town in decline towards being a diverse centre of modern architecture and green technology.

For every two Estonians there are at least three organisations

But the Estonian community has also always worked actively to preserve its national heritage and to raise awareness about Estonia through its many associations, societies and unions.

In fact, the quip “for every two Estonians there are at least three organisations” originates from Sweden. What is true, though, is that during the peak period, when Estonia was behind the Iron Curtain, there were some 400-500 Estonian organisations in Sweden. For many, the primary goal was restoring the Estonian independence and they worked tirelessly to lobby the Swedish politicians, media and the public.

When the Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, introduced some reforms in the communist empire in the late 1980s and the atmosphere became more liberal in Estonia, the long-lost contacts intensified.

Swedish Estonians – many of whom had never seen the country of their ancestors or only had blurred memories – travelled to Estonia, to find a country with crippling shortages of some basic commodities, yet with a newly found free spirit. In contrast, a number of lucky Estonian Estonians, who managed to visit Sweden in that period during the late 1980s and early 1990s, found themselves in what seemed like a different world at the time – it had a sort of a “kid in a candy store” effect on them.

Many Swedish Estonians as well as “proper” Swedes were eager to help Estonia during the difficult years just before it regained the independence and afterwards. From basic goods to vans and computers, much was donated. Know-how on how to survive and succeed in a free market economy also helped. Carl Bildt, the Swedish prime minister from 1991-1994, played a major role negotiating the withdrawal of hesitant Russian military forces from Estonia.

Security is back on the cards

Today, approximately 100 Estonian organisations are still functioning in Sweden. In Stockholm, there is an Estonian nursery school and an Estonian elementary school. The Estonian language weekly newspaper, Eesti Päevaleht, has also survived, and is based at the Stockholm Estonian House that functions as an important centre for preserving and developing the Estonian heritage in Sweden. Numbers vary, but approximately 25,000 people who could be considered Estonians, currently live in Sweden, most of them in the large cities such as Stockholm or Gothenburg.

Ironically, the security of Estonia and Baltic region is again – 26 years after the collapse of the Soviet Union – a matter of concern. The Association of Estonians in Sweden (REL) that just turned 60, celebrated its anniversary with an international conference, “The security in the Baltic Sea region – a historical overview and future challenges”. Guests attended, in addition to the Baltic region, from Australia, the US, Canada, Germany, the UK, Ukraine and elsewhere.

No doubt it was hoped by everyone attending that there would be no Iron Curtain vol II, separating Estonia and Sweden.

I

Cover: Historical records show that first encounters between the two neighbours began in the early Middle Ages. A viking boat replica (courtesy of Eesti Viikingid.) Please consider making a donation for the continuous improvement of our publication.

“Good old Swedish times” was illusion. Swedes gathered enough courage to expropriate some of German properties, no benefit whatsoever for the local population.