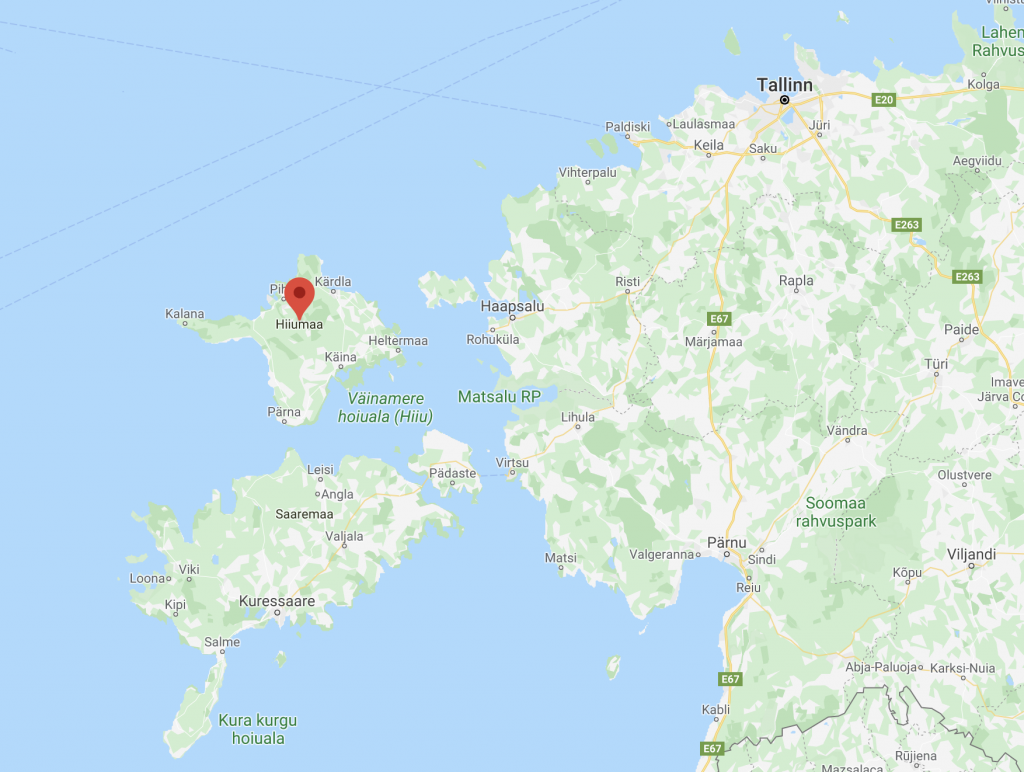

Iris van Genuchten, originally from the Netherlands, writes how she ended up in the Estonian island of Hiiumaa and fell in love with it, discovering the Estonian passion along the way.

Some encounters pass by gradually, almost unnoticed, until some years later that encounter turns out to be a key moment for your future life. I had such an encounter six years ago, in Portugal with a woman from Estonia – her name is Kadi Kenk. This is how, five years later, I ended up in the Estonian island of Hiiumaa and fell in love with it.

In 2015, I started my master’s in anthropology of a sustainable world in the Netherlands and was looking for a field site to conduct my graduation research. I knew I wanted to do something related to human behaviour towards waste. Somewhere in the back of my head I recalled the posts about fighting against the trash problem that Kadi Kenk had posted on Facebook. That’s when I also discovered the Estonian founded civic movement Let’s Do It! World.

“Hello, Kadi, it is a long time ago that we met, but I am interested in your organisation, what are you exactly doing? Hope to hear from you!” I wrote to Kenk, after not having met her for five years.

She responded instantly and a few weeks later I arrived for the first time in Estonia, in Hiiumaa, where Let’s Do It! activists were gathering for their summer event to plan a new season of activities worldwide.

That weekend, under the starry sky of Estonia’s second biggest island, I fell in love. I fell in love with Estonia – Hiiumaa in particular – and most of all with Let’s Do It! and the driving force behind the movement. It was so inspiring to see such ambitious and passionate people (never say passionate Estonians do not exist!).

That weekend, probably somewhere between a sauna, jogging along the beach or during a brainstorm in the field, I decided to spend my research time in Estonia with the Let’s Do It! team.

Never say Estonians are distant or not passionate

People back in the Netherlands warned me when they saw my glowing eyes when speaking about Estonia. “It is probably not going to be as nice as it was the first time,” they said.

Estonians simply declared that I was crazy coming here in winter. “Everyone wants to go away, see the sun, and you are coming here,” they expressed their disbelief in my decision. But after spending just two months in Tallinn, I did not regret my decision a single moment.

It is true, every Estonian I have met so far ridicules the cold nature of Estonians. But as they do it, it happens during a conversation that is far from either cold or distant.

In my short stay here, I experienced often a disparity between this ridiculing the supposed distant nature of Estonians, the surprise about me being voluntarily here in winter and my wish to learn at least a bit of the language, versus the pride about the nation expressed in people knowing the most random charts by heart. From the most models till the most start-ups per capita in the world.

For me, it is this combination that is so charming about the Estonians I met. Their natural friendliness towards others and pride in all that has been established within such a short time. Maybe that also makes the Estonians I know have the inspiring ability to dream big.

Maybe I have a rose-tinted view because I still know people mainly involved in the Let’s Do It! initiative, but, having said that, it is truly inspiring to see people working towards an amazing goal, creating something out of nothing.

To me, it seems this does not happen just in the start-ups and movements like Let’s Do It! – I tend to see the same pattern when looking at urban development for example.

In my Lonely Planet guide from 2011 for instance, Telliskivi Creative City is not mentioned at all. Meaning that people have managed to set up a creative and diverse gathering place from scratch within five years – a place that is now mentioned on every Airbnb description.

I will therefore repeat my point: never say Estonians are distant or not passionate. Down to earth? Yes. Good in small talk? No. But do not mix that up with cold or lack of passion. The self-evident way of being friendly made me feel warmly welcomed in this (OK – point taken – not that cold) winter and their entrepreneurial approach to seeing possibilities in empty buildings, technologies or waste, inspired me deeply.

Unfortunately, I am leaving again, but Let’s Do It! as well as the country and some friends I have made have, in more ways than I can describe, become part of my life. I will be back sooner or later, shorter or longer – preferably sooner and longer.

Cover: Kõpu lighthouse in Hiiumaa island. Photo by Jarek Jõepera.

From an Estonian living in the Netherlands: the culture and the way people treat each other in NL and EE are actually surprisingly similar. Outsiders often see it as rude or cold; but if you’ve grown up in this sort of a culture it’s more… no-nonsense, straightforward and honest. We go straight to the point, and if we make a deal, we do our best to keep the deal. If something can’t be done or we’re unsure, we say so straight away and explain why. None of that “yes” culture when actually… something just can’t be done. Particularly when it comes to work-related things, Estonians don’t do small-talk; the Dutch do it a bit more; but compared to the English-speaking world… One of the main differences is that the Dutch are generally quite open with their personal lives, Estonians prefer to keep a certain distance; or at least not volounteer information. Although, there are of course as many variations to the theme as there are people.

From a different angle though… how nature is perceived – Estonians almost revere wild nature, the forests, the bogs… It’s stated in the constitution that between sun-up and sun-down everyone has a right to go into any forest (except nature conservation areas but including private properties) and gather mushrooms and berries or just wander around. But a lot of Estonians tend to take the abundance of nature for granted, and so there are less protection measures in place which allows those with bad intentions to make mischief – this attitude of “oh well, we have so much forest, it’ll be fine” seems to be changing now though. In the Netherlands, there are very few wild areas left; and the ones that are still here are so strictly protected that most Dutchies have no idea what a wild forest really looks like. The famous Amsterdamse Bos (Amsterdam Forest) is… well, it’s a park. There are paved footpaths and manicured lawns and the trees are maintained and, let’s just face it: it’s a park. But on the other hand, in the urban areas, every tiny little piece of dirt has something growing in it. It’s looked after, it’s tended and it’s loved. And if there’s no dirt to plant things in, then people put pots out, with flowers growing in them. The gardens are tiny; in fact you’re lucky if you have any outside space at all! But you generally don’t see weedy patches or broken branches that have been left that way for a couple of years. It’s a more cultivated kind of love of nature… but I think it comes from the same place.

This is an interesting discussion about the straightforward nature of Estonians and Dutch folks. I am the American child of Slovak immigrants. In our little Slovakian descendants group we also got right to the point without much small talk. I thought every one did that until I grew up and got a job and learned that most cultures, as represented by their American immigrant children, don’t get to the point. They would rather waste time talking and being nice to each other, but never get things out n the open and settled and done. It was a relief to work with other children of Slovakian immigrants. I think a Dutch or Estonia sociologist would have fun coming here to American to study the way the children of the different immigrants have internalized the attributes of the mother cultures.

In early 2014 I was doing an internship at ELF in Tartu and I can only share your positive experience Iris. The innovative, friendly and ambitious way of how the people of this NGO work is highly inspiring and fascinating! As well as how big the influence of young people can be within a country, compared to antiquated German leading structures for instance.