Denis Filby, an Englishman who divides his time between London and Tallinn, says the Estonian government needs to do more to appreciate teachers before they’re all gone.

During the past ten years, I have spent time travelling equally between the UK and Estonia, so it should be no surprise that I have compared life and attitudes in both countries.

As an Englishman, I often thank the Estonian education system that has taught youngsters to speak my language. Not only English on a basic level, but the best students often have a knowledge of grammar, spelling and general usage that equals, and sometimes surpasses, many English people. I see this especially clearly, since my Estonian partner is an English teacher.

It is always a delight for me, as well, to witness the enthusiasm that surrounds the start of the school year in September. The spectacle of eager schoolchildren embarking on their first day at school, dressed in bright new uniforms, carrying flowers, supported and encouraged by their families and monitored by older students.

Of course, youngsters in the UK are equally enthusiastic when starting school, but the important national and social tradition of support is lacking. The sad state of the UK’s education system is frequently discussed in the British media with the focus being given to falling standards and meaningless exam grades, as well as the all-too-common shortage of teachers.

A shortage of teachers

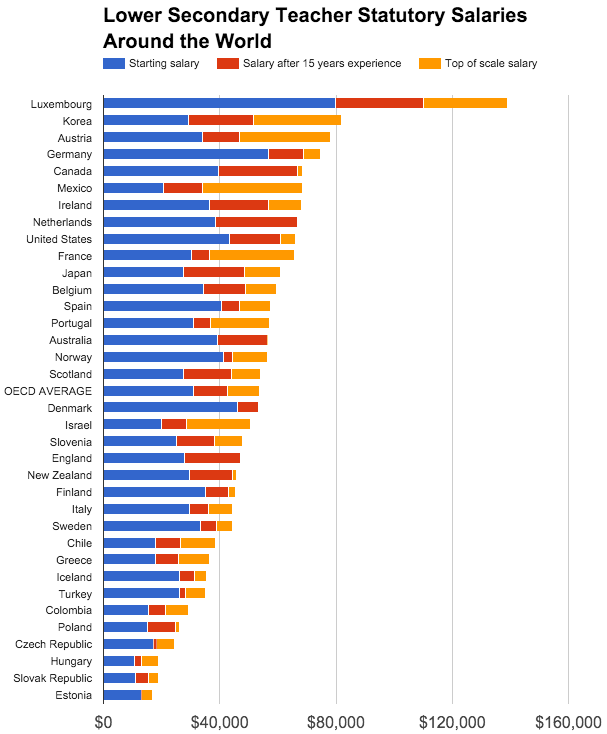

In a recent BBC news item, education experts in the UK were saying that Finland ranks so highly in academic achievement because it pays its teachers a good salary. Yet little Estonia, with its poorly paid and unappreciated teachers, is at the same high level as Finland. How can this be?

What concerns me is that Estonia could be headed the same way as the UK. From a bright start, where Estonia is usually in the top ten of the world Programme for International Student Assessment rankings, there are dark clouds on the horizon.

For example, there is a serious shortage of teachers. Mathematics and English language teachers are among the most sought after, with recently-retired teachers being persuaded back into service and even some with no teaching qualifications being given jobs.

Teachers in Estonia are some of the lowest paid

Estonian politicians will tell you they have given teachers a pay rise. But a small increase on a meagre amount is not enough in a country where inflation is making everyday life difficult for those on low incomes. The system seems to be heavily reliant on older, dedicated women who are afraid of standing up and protesting too much. In 2016, a report noted that “with half its teaching profession at secondary level aged 50 or more, Estonia faces a generational turnover in the coming years”.

So, why is there a shortage? Well, pay is one obvious factor. Few young graduates can afford the pleasure of becoming teachers if they want to buy a home and raise a family. Only nine per cent of teachers are under 30 according to recent figures, with women making up 82 per cent overall.

Based on OECD statistics, teachers in Estonia are some of the lowest paid worldwide, even after adjustment for the cost of living. So from education achievement ranking in the top ten, we go to financial reward ranking at the bottom.

Another reason for poor recruitment could be the way in which teachers have lost much of the respect they once enjoyed – many parents, politicians and educational theorists, believe they know how best to educate youngsters!

Meddling in education has become the vogue

Meddling in education has become the vogue. Those who advise but do not teach suddenly become “experts”, telling teachers with many years’ experience (and, of course, good results to show for it) how to do their job. Courses are set up and “improvement” seminars are organised that take up more of the teachers’ free time to tell them “how to teach”.

And that is another issue – free time. Many will think, understandably, that teachers enjoy generous weeks of paid holiday each year. Think again! Just because students have a holiday, it does not mean that teachers enjoy the same benefit. Teachers will be back at work two weeks before the start of the school year, and during the term holidays, they often must attend those “improvement” seminars, usually in the middle of a week when they could otherwise go away. And that is not counting the unpaid extra day evening and weekend work needed to prepare lessons and grade tests.

So what is the answer? Well, the simple answer would be for teachers go on strike until the government sets higher rates of reward. But that will not happen. First, because teachers are too dedicated and second because they are too financially reliant on the small pay they get. Also, politicians will finesse the argument to make it appear that teachers are being unreasonable.

That is until someday, quite soon, when someone in government asks the question, “Where have all the teachers gone?”

I

The opinions in this article are those of the author. The cover image is illustrative.

Dear Dennis, I read your letter with great interest. I too have been coming and going for over 15 years and like you, have watched with interest how Estonia has developed and progressed.

My specialization is in ESP, so I am more involved in Business English and was not aware that there was such a dearth of teachers here.

Many thanks for your illuminating inclusion.

Michael