Estonia and its fellow Baltic countries joined NATO on 29 March 2004, but the story of its path into the alliance goes much further back, as Adam Rang explains; a rarely seen document shows Estonia was already working towards membership in 1949, despite the country’s occupation by the Soviet Union.

The security strategy of Estonia over the last three decades can be best summed up in three words. “Never again alone”.

Those words were uttered by a former Estonian president Lennart Meri when, on his 75th birthday, the Baltic countries joined NATO on 29 March 2004.

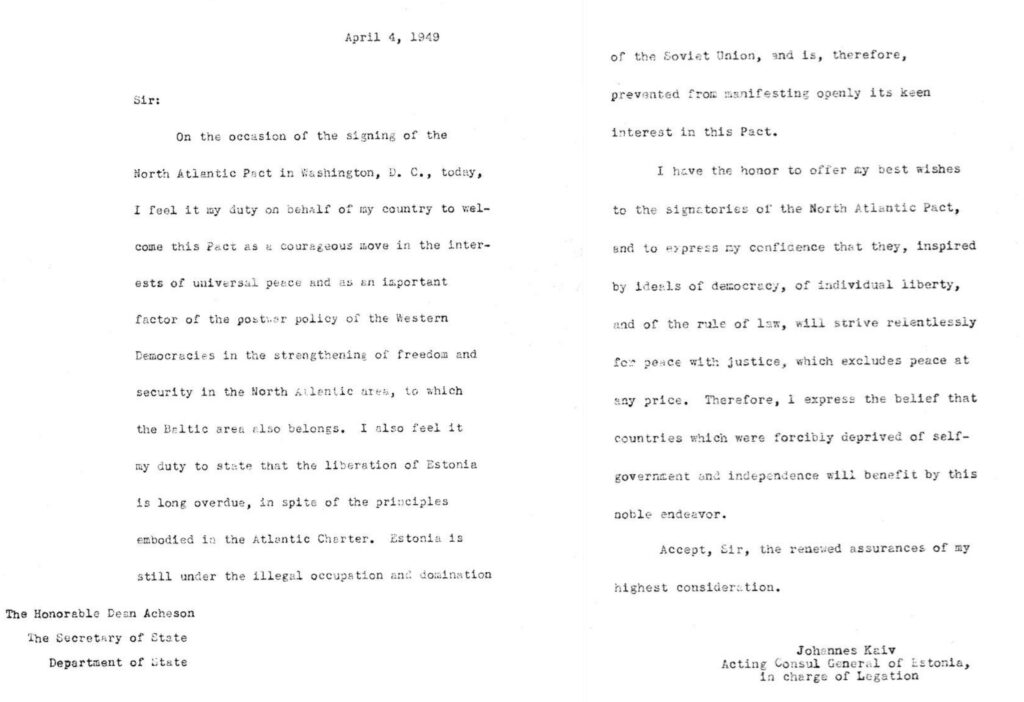

NATO was described by Estonia as “a courageous move in the interests of universal peace and as an important factor of the poster policy of the Eastern democracies in the strengthening of freedom and security in the North Atlantic area, to which the Baltic area also belongs.”

Such platitudes would hardly be a surprise 19 years ago.

Estonia had fully restored its independent state just over a decade earlier and had worked relentlessly on the democratic reforms necessary to join NATO as well as the European Union and cement itself into the Western alliance of democracies.

Except, those words weren’t penned 19 years ago.

To understand Estonia’s journey into NATO, you have to go much further back. That description of NATO actually comes from a rarely seen statement issued by Estonia 74 years ago during the founding of the alliance on 4 April 1949, the anniversary of which will be marked next week.

“Estonia is still under the illegal occupation and domination of the Soviet Union,” the statement, written by Estonian diplomat Johannes Kaiv, continues, “and is, therefore, prevented from manifesting openly its keen interest in this pact.”

“I have the honor to offer my best wishes to the signatories of the North Atlantic Pact, and to express my confidence that they, inspired by ideals of democracy, of individual liberty, and of the rule of law, will strive relentlessly for peace with justice, which excludes peace at any price. Therefore, I express the belief that countries, which were forcibly deprived of self-government and independence will benefit by this noble endeavor,” the letter said.

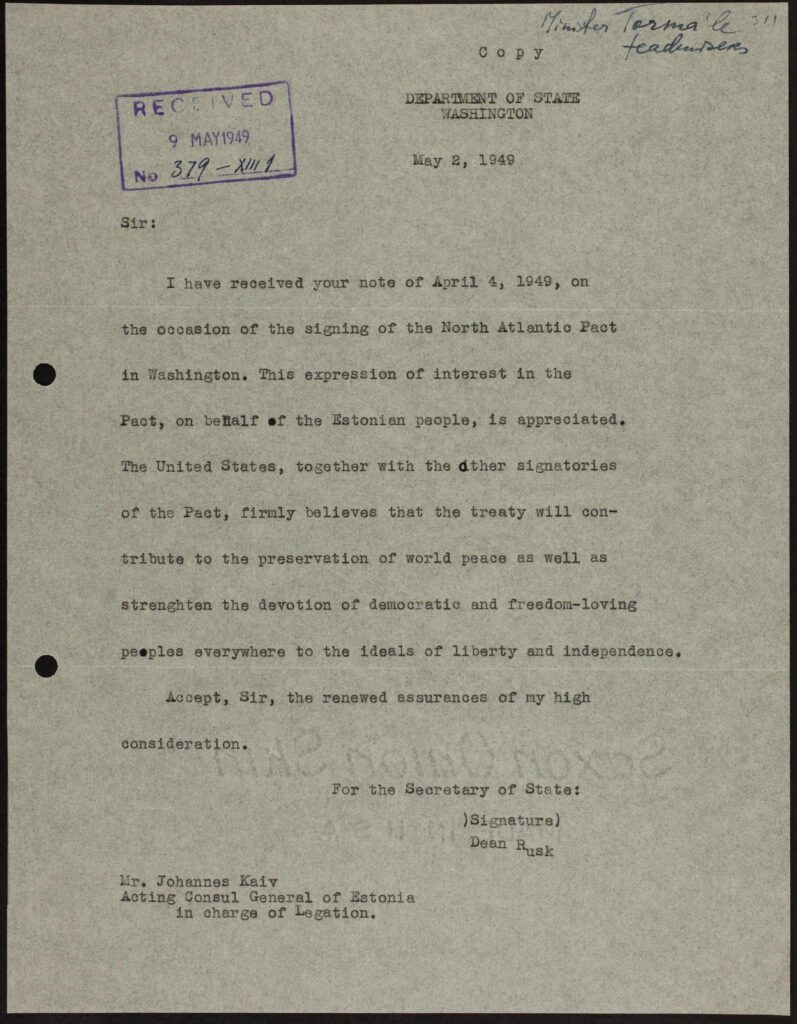

Estonia’s expression of interest in NATO was formally noted, as shown in this response from the US undersecretary of state at the time, Dean Rusk, who later served as the secretary of state to the US president, John F. Kennedy.

Latvia and Lithuania issued similar statements in 1949, all welcoming the creation of NATO and their belief that it would benefit the world, including nations such as theirs then under occupation.

Defined Estonia’s position

The Estonian foreign minister, Urmas Reinsalu, told Estonian World that the statement in 1949 defined Estonia’s position in Europe as the country never surrendered to the Soviet occupation.

“As Estonia celebrates 19 years in NATO, a whole generation has grown up in the safety and under the security umbrella of the alliance,” Reinsalu said.

“As Russia’s aggression in Ukraine continues and Europe faces its biggest security threat since the Second World War, I am grateful for the unity NATO and its members have shown in responding to it. But this new geopolitical situation has shown that there can be no grey zones in Europe and I hope that soon we can welcome Ukraine in the alliance.”

The story of NATO, like the story of the Baltic countries, is often told from the perspective of “great powers” with the assumption that small countries between them have little agency in the seemingly inevitable historical changes thrust upon them.

But these letters are the start of the NATO story from the perspective of the Baltic countries, which blows apart that narrative.

How were these statements possible?

Throughout their long occupation, the Baltic states remained independent in both their own domestic law and in international law.

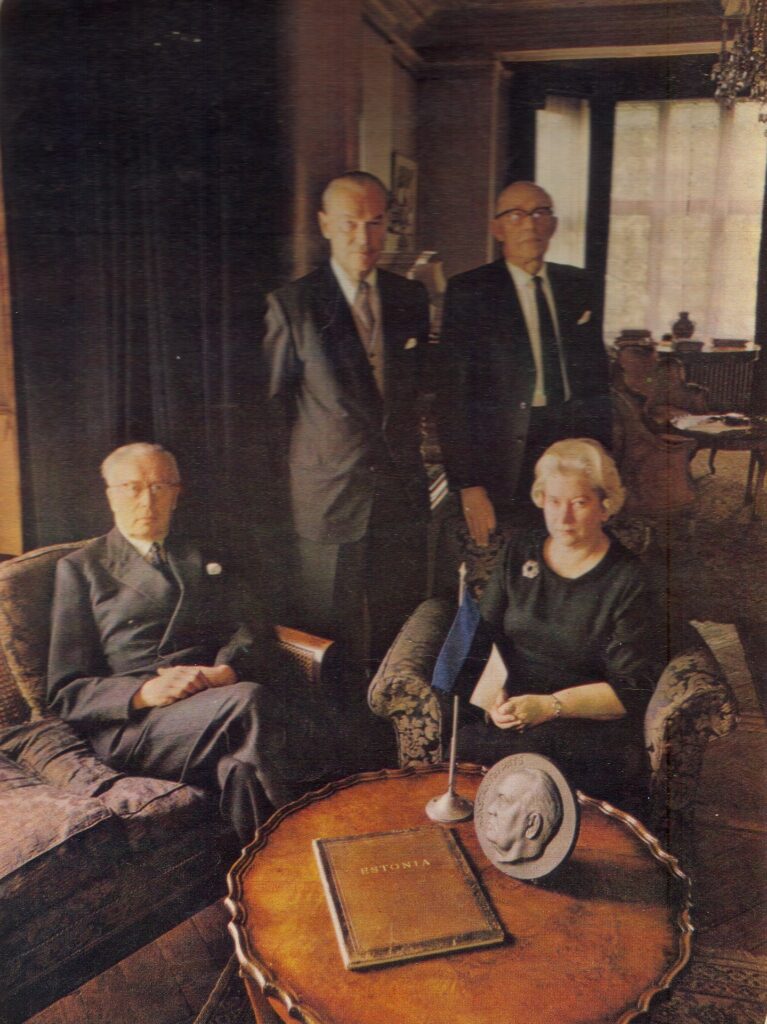

To many around the world, this seemed largely theoretical given the grim situation on the ground. But there was one part of their states that the Soviets were unable to dismantle. The foreign ministries of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania continued to function – in exile.

Their diplomats stationed abroad continued showing up to work in countries that continued to respect the independence of the Baltic states, even though those diplomats temporarily had no legitimate governments back home to report to. The Soviets tried to convince countries that diplomatic buildings belonging to the Baltic states should be handed over to the Soviet Union, but some refused – most notably, the US, UK and Brazil.

This enabled the Baltic states to partly function independently in exile, such as by issuing passports. Most crucially, however, it provided a continued official voice for the Baltic states, educating the world that the Baltic states were still legally independent and were working to fully restore their states.

As they pointed out, the Baltic countries were forcibly and illegally annexed by the Soviet Union in 1940 as a result of its collusion with Nazi Germany to divide Europe into spheres of influence, as outlined in the secret protocol of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.

This violation of international law led to the Second World War, sparked first by the Nazi invasion of Western Poland, but which was shortly followed by the Soviet invasion of Eastern Poland. The Baltic countries declared neutrality at its outbreak, unaware that they had already been consigned by both aggressors to Soviet invasion.

The Nazi-Soviet alliance was maintained for the first two years of the Second World War before the surprise attack ordered by Hitler on the Soviet Union. Yet, at the end of the war, the Soviet Union re-established its grip on the Baltic countries and continued its own occupation, which it justified through the staged annexation that took place by force in agreement with the Nazis.

This situation meant the Baltic states were the only members of the pre-war League of Nations not permitted (until much later) to join the post-war United Nations.

Even many of those around the world who supported the plight of the Baltic countries regarded the noble work of exiled diplomats to be a lost cause. The restoration of international law for the Baltic states looked, for a long period, like a pipedream. Yet they continued their work regardless.

For example, when NASA in 1969 requested goodwill messages from the nations of Earth to be sent to the moon onboard Apollo 11, official statements from both Estonia and Latvia were included.

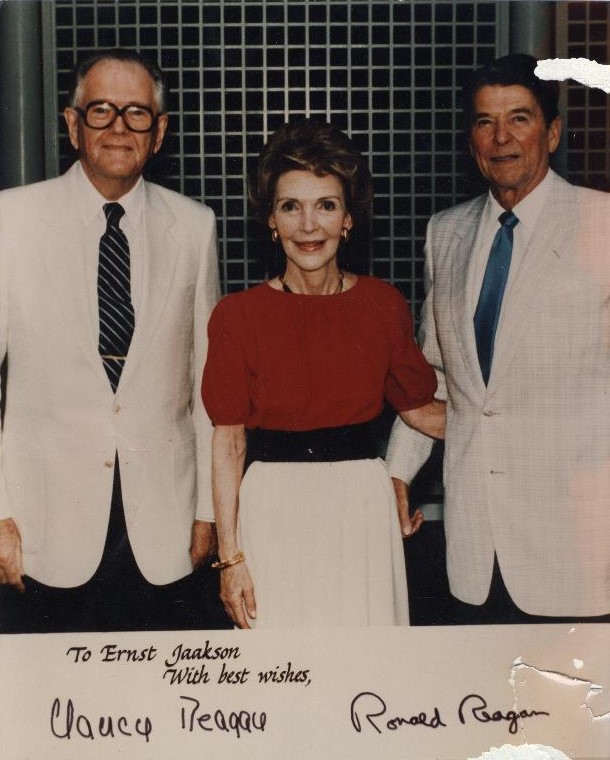

“The people of Estonia join those who hope and work for freedom and a better world,” declared Estonia’s consul general in New York, Ernst Jaakson, on behalf of Estonia.

“On behalf of the Latvian nation I salute the first men on the Moon and pray for their safe return,” said Anatols Dinbergs, then head of the Latvian diplomatic service. “May their achievement contribute to world peace and restoration of freedom to all nations.”

History vindicated them.

Jaakson and Dinbergs, for example, both appointed by their pre-occupation governments were both promoted to ambassadors by their post-occupation governments.

The Baltic states did not “become independent” from the collapse of the Soviet Union, as too often described. They formally declared that their illegal annexation was null and void, and that occupation troops must leave, helping facilitate a chain reaction across other captive republics that ended the Soviet Union.

It is partly thanks to exiled diplomats the Baltic countries exist today based on their legal continuation since their founding as republics in 1918.

This means their statements in 1949 welcoming the creation of NATO and indicating the Baltic states should be members was – and still is – the official position of the Baltic states at that time.

The Baltic path to NATO

Expressing a desire to join NATO is not enough to join the alliance though, even after the end of occupation and the full restoration of the state.

Every existing NATO member state has to be convinced that an applicant country meets the rigorous requirements, which includes having a robust, functioning democracy with an independent civil society and both the ability and willingness to contribute to the security of the alliance and the wider world.

Even with the rapid progress made by the Baltic countries in their first decade after occupation, there were still many politicians in both Europe and the US who were sceptical or outright opposed to the prospect of NATO membership for the Baltic states. Their reasoning, now obviously faulty, was merely that these countries had spent too long under Russian domination to integrate successfully with the Euro-Atlantic security architecture or should wait for a more opportune moment when relations between the West and Russia had improved further.

Yet Baltic leaders and officials adamantly demonstrated to policymakers across Europe and the US that their countries were suited to the alliance of democracies and would make a positive contribution to all members.

Daniel Fried, once the top US diplomat in Europe, explained in a speech looking back in 2017 that “the real credit for all of this, for the Baltic states coming into NATO and the European Union belongs to the people and governments of the Baltic states. Don’t thank us, us Americans who were involved in the policy. Because if the Baltic states had failed in their democratic free market transition, I wouldn’t accept the blame.”

“My point is that the heavy lifting was that on the part of the Baltic states, the political parties, the societies, the people. They did it. They made a success of their transformation to democracy. … There were reasons, one of them being that in 1989 and 1991, being normal and part of Europe is still living memory in the Baltic states. People remembered what a normal country was, and they wanted it back.”

The tipping point was reached in the summer of 2001 when the US publicly indicated its strong support for the prospect of the Baltic states joining NATO, as outlined in a speech by US president George W. Bush. Even Russian officials indicated in early September of the same year that they had accepted it as inevitable.

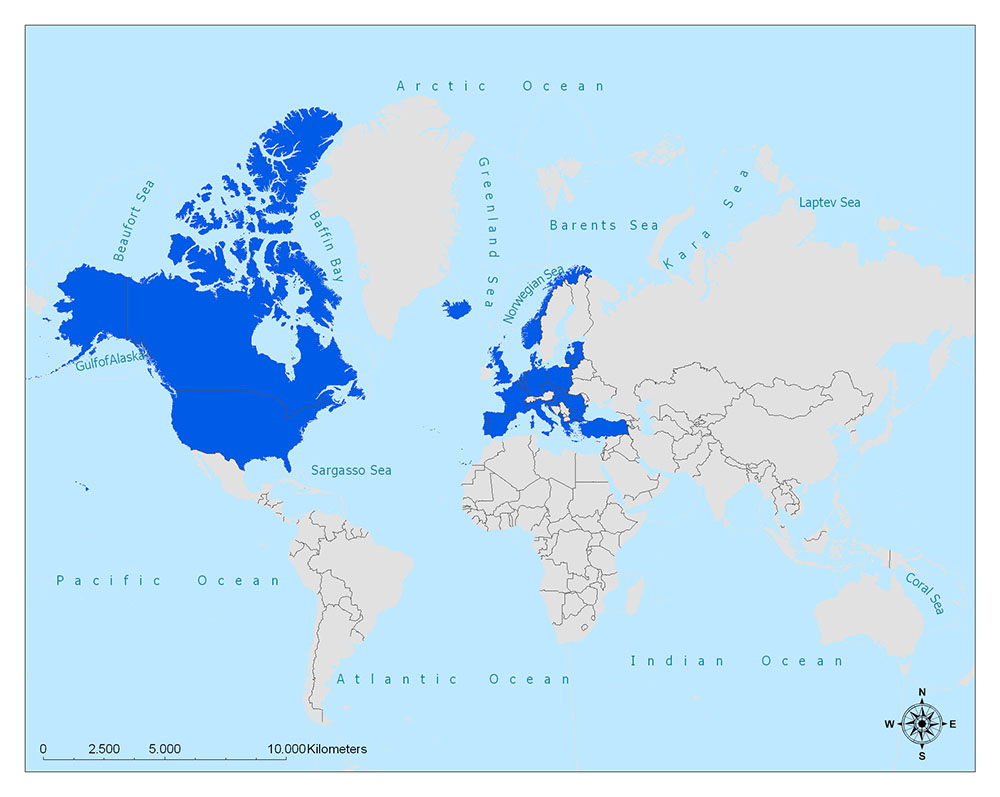

The Baltic states were formally invited to accession negotiations in 2002 in line with Article 10 of NATO’s founding charter – welcomed more than half a century earlier by the Baltic states – that membership is open to any “European State in a position to further the principles of this Treaty and to contribute to the security of the North Atlantic area”. They joined two years later.

The Baltic entry into NATO is often described in media reports and commentaries as the first time NATO bordered Russia. In fact, NATO was founded with Norway’s land border with Russia, as well as the US maritime border.

So far, this story has not touched upon opposition from Moscow to the Baltic states joining NATO. That’s because it didn’t happen to any significant extent, despite the revisionist claims made by Moscow today.

When Vladimir Putin became the Russian president in the years leading up to the Baltic states joining NATO, he insisted the alliance was not an enemy and even suggested repeatedly that Russia be invited to join (as long as it didn’t have to face entry requirements like other members, which was a non-starter).

As Baltic membership of NATO loomed, Russia’s position on the matter was largely in line with its commitments under international law to respect the fact that every sovereign country has the right to choose its own security alliances. When Putin was asked about the prospect of NATO enlargement in 2001 during an interview with NPR (National Public Radio) in the US, he reiterated that “we cannot forbid people to make certain choices if they want to increase the security of their nations in a particular way.”

This is also in line with the NATO-Russia Founding Act, which was agreed in 1997 with both sides clearly confirming that all sovereign nations have the right to choose their own security arrangements. Russia requested a veto on NATO membership applications, but this was rejected.

In the interests of furthering cooperation, however, NATO made several significant concessions, including to avoid stationing permanent substantial combat forces on the territories of NATO countries that were former Warsaw Pact states (even if they were illegally incorporated in the case of the Baltic states). It should be noted here that the Warsaw Pact was a mere imitation of a defence alliance with the ignominious distinction that it attacked its own members.

But, as part of the NATO-Russia Founding Act, NATO agreed to only rotational deployments in former Warsaw Pact countries for the purposes of drills and integrations, a condition that NATO has respected to this day, despite the complete departure from commitments to the agreement and international law more broadly by Russia as the other signatory to this agreement.

It was only after the Baltic countries joined NATO that Russia’s descent into ever deepening authoritarianism and imperialism resulted in relations with the West significantly deteriorating, after which Russia switched to heavily promoting false narratives that Russia had been betrayed by NATO enlargement.

Most notably, Russia now claims that the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, was given an assurance in 1990 that NATO would not expand east of Germany. This assurance is not only not contained in any legal agreement, but undocumented and not remembered by anyone involved – including Gorbachev himself who told Russian state media in 2014 that there were no discussions on NATO enlargement at the time, only assurances on limiting deployments to the now former East Germany, which were legally agreed and adhered to by NATO.

For one thing, it would be strange if the Soviet Union was negotiating arrangements for after its breakup at a time when it didn’t foresee that breakup or that it could expect to overrule sovereign nations that outlived it.

Another now consistently used Russian propaganda line targeted more specifically at the Baltic states is that NATO would be too weak or unwilling to defend them if they were attacked. This is somewhat less convincing when Russian propaganda is simultaneously arguing that NATO seeks every opportunity to confront Russia and is to blame even for its failings in a war against non-NATO member, Ukraine.

Russia continues to occasionally reference NATO “expansion” as a justification for its brutal war of aggression against Ukraine, yet far more prominently outlines its real desire to illegally annex Ukraine into Russia on the basis that it doesn’t believe it even has a right to exist as a sovereign nation.

Ukraine was actually committed to neutrality when Russia began the war in 2014. Meanwhile, Russia has consumed much of its own forces stationed near the Baltic countries and has voiced relatively moderate opposition to Finland and Sweden’s desire to join the alliance, prompted by its actions.

While Russia was assembling its full-scale invasion force around the borders of Ukraine, it issued a demand that NATO forces should withdraw from the Baltic countries and Eastern Europe. This, absurdly, would have meant the withdrawal of Estonian forces from Estonia, Latvian forces from Latvia and Lithuanian forces from Lithuania.

The same absurd language is too often used in the Western media too, which sometimes talks about the size of NATO forces in the Baltic countries while forgetting to include the fact that the armed forces of the Baltic countries are also part of NATO – or talks about the “further Eastward expansion” of NATO to a country like Sweden that it is actually to the West of the Baltics as NATO members.

Never again alone

The mantra of “never again alone” has been repeated by NATO allies, too, including by a former US president, Barack Obama, who said in his 2014 speech that Poland and the Baltic countries would never again stand alone. The incumbent US president, Joe Biden, along with other NATO allies, have also repeatedly insisted they are committed to defending “every inch of NATO territory”.

Recent public opinion polls across the Baltic states reveal that support for NATO membership remains high, as does confidence in the ability of their country to resist an attack alongside allies.

In the latest annual public opinion survey of Estonian residents commissioned by the country’s defence ministry, support for NATO remains high at 80%, while 70% consider NATO membership to be the country’s primary security guarantee; 69% think NATO has done enough to support Estonia’s security, and 69% again think allied NATO forces stationed in Estonia make it safer to live here.

In addition, two thirds of Estonia’s residents say they would definitely or possibly participate in defence activities in the event of an armed attack, while 60% of residents believe Estonia can defend itself until allied reinforcements arrive. Interestingly, both these figures have risen quite significantly since Russia began its war on Ukraine.

Finally, more than half of Estonia’s residents said they supported increased defence spending.

Estonia is one of the few NATO members that surpasses the agreed target of defence spending at 2% of GDP, but all political parties represented in Estonia’s parliament support increasing it to 3% for at least the next five years. Prime minister Kaja Kallas and her potential new coalition partners also plan to call on all NATO allies to increase their spending to at least 2.5%, while clarifying that this was the minimum expected.

Estonia has also repeatedly affirmed it is ready and willing to defend every inch of NATO territory. “Never again alone” also means being there for allies. Estonian forces take part in missions abroad as part of NATO as varied as counter-piracy and peacekeeping, while also contributing specialist skills in areas such as cyber defence.

Prior to joining NATO, many voices in the West didn’t understand the urgency with which the Baltic countries saw their opportunity at the time. The Baltic countries correctly predicted that it may have actually been their only window of opportunity.

As an Estonian foreign policy memo explained shortly after independence, crystalising the urgency of reforms and integration into the European security architecture, “time is short and time does not wait for small nations”.

These letters in 1949, and everything that has happened since, show that NATO is as much an alliance to which the Baltic countries belong as any other members. Were it not for occupation, Estonia may have been celebrating the 74th anniversary of membership next week. Instead, Estonians have two occasions to remind themselves and the world just valuable it is.

Very nice article, Adam! I had never heard that Estonia sent a greeting to Apollo 11. Very neat!

So you say that various Estonian embassy buildings were allowed to remain working during the occupation years. Where did funding come from to retain / operate the embassy buildings, the staff?

The Estonian government wisely had Gold reserves outside of Estonia.

The interest of the Estonian reserves was said to pay for the Estonian government in exile.