On 9 March 1944, the Soviet Air Forces started to bomb the Estonian capital, Tallinn, that, at the time, was occupied by Nazi Germany; some 600-700 civilians died, over 600 were wounded and some 20,000 people were left homeless; Estonian World publishes an excerpt from the book, “Darkness in Tallinn: World War in Europe’s Forgotten City”, by Ian Thomson, an English writer and a senior creative non-fiction lecturer at the University of East Anglia, the UK.

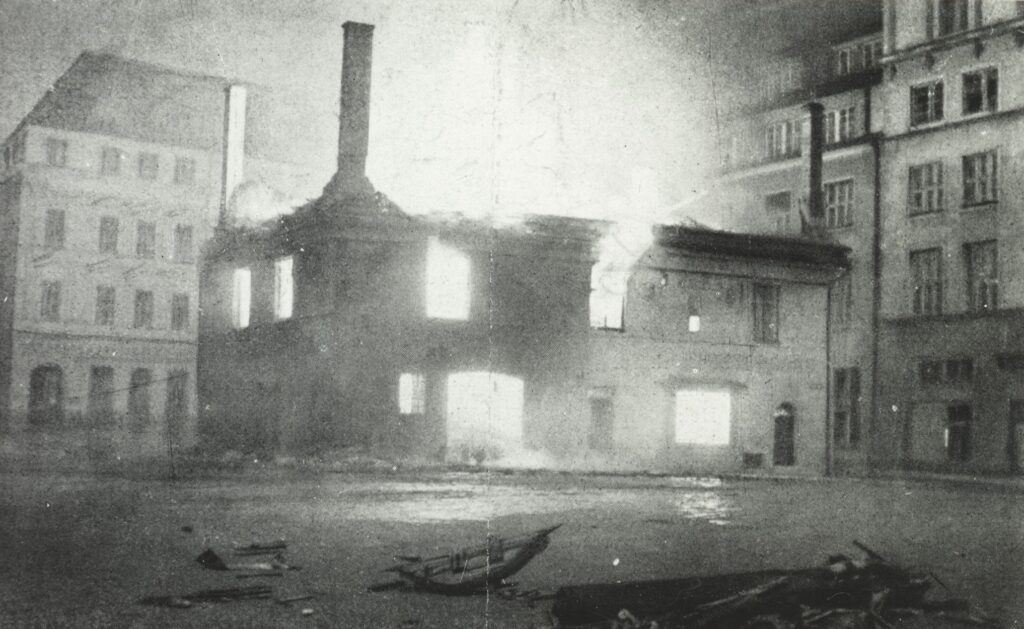

On 9 March 1944, early in the evening, Soviet Russia began to bomb Tallinn. The skyline turned dark; clouds of cinders, lit red by the blaze, floated down over churches, medieval towers and stone-flagged streets. The mile-high roar of magnesium incendiary flames created a firestorm in which 600-700 civilians died (the final count is uncertain), some 20,000 were made homeless and over 600 left wounded.

Life as Tallinners had known it, came to an end that March night. In a matter of hours, buildings and people were torn apart and crushed. Residential districts, hotels, cinemas, factories, a synagogue, hospitals, warehouses – all obliterated. Few could endure more blackout, bombs and sirens; those who could, left – on lorries, on foot, on over-crowded trains. Among them was my mother, who was fourteen at the time. She would not return to her birthplace for over half a century.

Shortly before the attack, at about 5:40pm, the sun had gone down in a strange pale glow. There was a grandeur to that sunset which turned the onion domes of Alexander Nevsky Cathedral a delicate gold-pink. Trams clanged up Adolf Hitler Strasse (formerly Narva Road) and round the medieval Old Town walls.

It was snowing lightly and flakes fell on the waters of Tallinn harbour and the Gulf of Finland beyond. In cinemas the matiné show of the day had just ended. Der unmögliche Herr Pitt (The Impossible Mr Pitt), a German adventure-thriller set in Sicily and in far-distant Tunisia, was showing at the Kungla, while over at the Mars the box office hit was Magda, starring Nazi Germany’s biggest diva, the Swedish-born Zarah Leander. Both cinemas would soon be destroyed. It was a full moon and everyone agreed that it was a beautiful evening: a moon so bright was unusual for that time of year.

At approximately 6:20 pm came the first siren wail. Within minutes, anti-aircraft guns opened up with a spit of tracers, sending ribbons into the sky, as low-altitude Soviet pathfinder planes dropped green and red marker “Christmas tree” flares to indicate targets. The flares cast a bright-coloured chemical light as they swayed slowly down by tiny parachute. The play of twinkling reds and greens against the evening sky was beautiful in its way. On the streets below, those who had not stayed indoors for black-out looked up in wonder. “Birds sang at the unexpected appearance of daylight,” recalled one witness.

Much of Tallinn was now exposed to attack. Having breached the German flak defences to the east, an estimated 240 bomber planes flew in high over Lake Ülemiste near the airport. The Ilyushin 11-4 made a distinctive low hum as they unleashed their deadly combination of bomb blasts and incendiary chemical devices. The bombers came in waves at fifteen-minute and half-hourly intervals. Eye-witnesses said they heard a “shuddering” like an express train before the city was consumed by a smoke so dark that it seemed to force the pace of night. Frightened, Tallinners took to the boiler rooms, cellars and stairwells of their apartment buildings if they could.

Through it all, the moon was a steady spotlight over Tallinn, treacherously lighting up targets. By 7:15pm, there were not enough stretcher parties at the Deaconess Hospital on Pärnu Road where Estonian nurses in German uniform were putting up blood transfusions and saline drips. Morphia was in short supply too but the wards were crowded with casualties and harried-looking doctors. The clove sweetness of anaesthetic and pungency of dried blood thickened as the death toll mounted though the night.

The first attack would, by the end, last almost three hours until 11:00pm. The Golden Lion Hotel at 40 Harju Street took a direct hit, as did the neo-classical Estonia Theatre and Concert Hall building, where the Estonian composer Eduard Tubin’s 1944 ballet Kratt (“The Goblin”) was in its second act. A wall caved in with a sound like cracking plates and the concert-goers hurried down into the levels below ground. All this while the full moon continued to gleam steely and bright – a bomber’s moon.

Flames driven by the wind roared tall as houses on Harju Street where the fashionable cafés Feischner and Eden, the Amor cinema and Astoria restaurant were all destroyed. In the Amor alone, 150 people died. They died while watching the romantic German comedy Immer nur Du (You, Only You). The film had brought a touch of swing to Tallinn with its Fred Astaire-style style dance routines and the hit song, “Darling, What Will Become of the Two of Us?” The fire set light to the cinema’s celluloid stock which blazed the night long.

Early in the raid, a bomb had set fire to the City Archives and its repository in the Old Town on Rüütli Street. Epp Siimo, the assistant archivist, stared in horror from her house at 6 Rüütli Street, and decided to salvage what she could. Rudolf Kenkmaa, the chief archivist, was unable to leave his home in Nõmme suburb: Siimo was on her own. Her path to the repository at 1 Rüütli Street was blocked by a giant gilded weathercock which had come crashing down from the burning Swedish church. Her eyes smarting in the heat, Siimo approached the repository in the intensifying heat. From the third floor she managed to rescue and carry downstairs boxfuls of photographs and newspaper collections. A sudden detonation whipped her face; St Nicholas Church at the far end of the street had been hit: the spire burned like a candle and the flames sent hot air gusting down the street at gale-force pressure. Sipp was about to turn back when down Rüütli Street came a police battalion. She urged the police to barricade the repository windows against the flames, which they did by fitting metal sheets grabbed from a hardware store nearby: priceless manuscripts were thus saved. The German authorities later awarded her 200 reichsmark for her “special valour” (about £400 in today’s terms), but she chose to donate the money to a children’s charity.

My mother was sheltering in the cellar of the family home at 71 Tartu Road with her parents and sister. Between them they had a couple of emergency suitcases containing gas masks, a change of clothes, passports and other documents. The cellar shook and my mother held her nerve as a hail of shrapnel fell in the garden. The splinters made an eerie whistling noise close to her bedroom. The cellar’s one electric light flickered from the concussions above-ground and dust sifted down.

By 9:15pm, the raid seemed to have died away. Puffs of flak-burst hung in the air. A lull of four hours ensued. The moon hurried behind scattered clouds. During that time Tallinners emerged shaken from their shelters and basements, from under stairs and kitchen tables. In twos and threes they hastened through the deserted streets. Across Kreutzwaldi Street lay six dead German army horses: a bomb had hit their stable. The destruction was inexpressible; burning roofs and gables, burning rafters and burning advertising hoardings, and now these horses blackened and bleeding where a bomb had flung them.

The Tartu Road house had survived at least. My mother watched the last of the Red Air Force bombers departing for Leningrad through gaps in the smoke-clouds. On – on – and out of sight. The hum of the aero-engines diminished and then there was silence again. Tartu Road was left acrid with a smell of burning and sour debris. The heat prickled the skin. The Massoprodukt furniture factory at 73 Tartu Road was “burning completely out”, my mother recalled. From a distance she watched as the roof caved in amid sparks and secondary detonations of gas and fuel. Nothing could be more dreadful than this city my mother loved so much being devoured by fire. Her father, wasting no time, moved chairs and tableware out into the garden away from the furniture factory’s fire. He was helped by the Russian Orthodox priest, Alexander Jürisson, who lived in the adjacent flat with his wife Larissa and daughter Ariadne. In the moonlight under the still falling snow the men appeared as ghostly silhouettes. Orange-red flames from the burning factory were reflected off the walnut polish of the dining table and chairs dragged outside.

Some time after 1:00am in the morning came the second attack. Although less ferocious than the first, it was still purposefully cruel, this time with 60-70 bombers. Standing in Tartu Road my mother watched the flares sail down once more like spangles off a “Christmas tree”, when suddenly there was a detonation. She only had time to hurry back into to the cellar of 71 Tartu Road when the house windows showered down onto the street. Before long, she recalled, a “second sunset” of orange and rose had spread over all Tallinn.

The all-clear (“Raiders Passed”) came at about 3:00am and signalled the end of the second and final attack. When day broke it was seen that bombs had ploughed up the streets like a field and that much of Tallinn was no longer habitable. Back on Tartu Road there was still a dusting of snow and, again, no noise. Corpses lay fire-blackened and unrecognisable by the roadside and bluish phosphorous flames flickered round them. In the destruction’s aftermath relatives searched for their loved ones and tried to find some meaning in their deaths. My mother and her parents and sister were alive, but they could not possibly stay on in the shattered city. In one blasted room on Tartu Road the pictures hung askew on the wall and half a staircase lead nowhere. Only the facades of some buildings survived, and these were hung over with an odour of brick dust and mortality.

In a daze my mother walked down Tartu Road towards the Old Town. At number 20, the Salamander shoe factory was a mess of exposed roofbeams and twisted iron. A throng of bombed-out men and women, white-faced and bedraggled, passed my mother on their way to Lake Ülemiste where they hoped to find quantities of clean water. “There’s nothing left in town. You can’t carry on there,” they said to her. “Everything’s burning there. There’s no point in going any further.” At a certain point, Tartu Road no longer existed; there was not even a discernible path through the ruins. My mother felt as if she was in a “strange country” without maps to help her – she might as well navigate by the stars.

One incident has stayed with my mother: the destruction of her adored orange and lemon plants, which she had grown the plants from pips on her bedroom window sill. The blasts had shattered the window and sent glass and curtain-rods flying against the plants. She wept bitterly over the loss; her parents told her she ought to be ashamed to cry so when hundreds of people had lost their lives. In her child’s mind – as in any child’s mind – a personal trivial detail had become more important by far than a world historical event. The shallowness of her concern was not so very different in kind to that of Franz Kafka, when he noted in his diary for 2 August 1914: “Germany declared war on Russia; afternoon: swimming lesson.”

With 71 Tartu Road left to flame and ruin and no school left standing for my mother and her sister to attend, the family had to leave Tallinn. On the night of 10 March, a Friday, they were taken by a Wehrmacht lorry with other bombed-out Tallinners to a farm on the city outskirts, where they stayed for a week prior to their transfer to another safe place further south. Pathetic streams of evacuees pushed what remained of their property on sledges, on push-carts, with packs of stuff on their backs. The so-called “Flight from the East” – Flucht aus dem Osten – had already begun. Few civilians wanted to stay in Tallinn any longer. Rats moved among the ruins. My mother hoped for better times ahead, but as Tallinn smouldered behind her the feeling was of something irrecoverably lost. “We didn’t even have time to cry,” she recalled. “Everything – silver, furniture, photographs – went up in flames or was looted, I suppose.”

She was sure she would return as soon as the war was over, but the old days were gone – or almost. Half a century on, my mother can still remember the telephone number of her parents’ Tartu Road house: 31 954 – that, at least, nobody could take away from her. The last Soviet bombs fell on Tallinn on 22 September 1944, by which time the Red Army had advanced unstoppably on all the Baltic.

* This article was originally published on 9 March 2021.

I was there. Not quite nine years old, living at the bottom of Kaupmehe Street. Home alone with Dad – Mom had gone with friends to see ‘Kratt’ at the Estonia Theatre . . . . We lost our home that night and Mom ‘fell’ into the Air Raid’ ‘punker’ bleeding profusely some time after midnight. Methinks I remember each moment now at 87 . . .