Despite the fact that 23-year-old Nikita, born into a Russian-speaking family in Estonia, speaks fluent Estonian, studied for his bachelor’s degree in Estonian, served in the country’s military and holds an Estonian passport, he still feels unwelcome in Estonia.

A new project within the EU-Russia studies programme at the University of Tartu analyses personal stories that are based on people’s experience of living in Estonia.

The project is aimed at describing the multicultural society within Estonia – identities and integration in the Estonian cultural and political society. The goal is to collect a wide range of stories about non-native residents who call Estonia their home – individuals with diverse backgrounds who live, work or study in the country.

There is one thing common, however – they all claim some form of Estonian identity: be it national or cultural. These groups include, for example, the young generation of Russians, business professionals or academic individuals who may struggle with their identity and integration into Estonian society. The master’s students at the programme have now conducted 30 interviews. Over the coming months, Estonian World will publish a number of these personal stories to give our readers hindsight of people’s lives.

The first story comes from 23-year-old Nikita, who was born into a Russian-speaking family in Kohtla-Järve, a town in northeastern Estonia. His father was born in Estonia, however his parents met each other while studying medicine in the city of Petrozavodsk in Russia, and eventually moved to Estonia. Being born and raised in Estonia, he is deeply attached to his motherland. However, from time to time he feels unwelcomed here and he does not like to discuss it.

The only Russian in the group

I graduated from a Russian school and grew up surrounded by Russian speakers. So, of course, I soaked up some values and views from Russian culture and literature. However, when my parents divorced, my mother married an Estonian man, so I spoke the language with him and my skills were improving.

As a kid, I spent a lot of time in a remote village in southern Estonia, where our relatives live. They do not speak any Russian there. So, little by little I overcame the language barrier and began to speak Estonian. I also started watching movies and reading books in the Estonian language more often. In high school, the language programme they taught was not sufficient by itself. Yet before graduation, I passed the state language proficiency test at the highest level. So after school, I was able to apply for the Tallinn University of Technology, where I was the only Russian in the group.

A deep divide between Estonians and Russians

I think our country has a deep divide between Estonians and Russians. Those who do not speak the state language are not accepted and remain isolated from the Estonian society. Many are not able to work or find a profession. The penalty for not knowing Estonian, while working in the public service, can be a fine or even losing your job. For example, my Russian language and literature teacher in school was fired for not having an Estonian language certificate. My mother used to pay the fine, but she tried hard to learn the language and passed the state exam. But for those who have worked using only Russian for most of their lifetime, it is a big challenge to pass the Estonian language test at a sufficient level.

The ability to speak the state language is one of the most important steps of integration that we, as Russian speakers, have not fully overcome yet. If a kid is born in Estonia, it does not automatically mean they will start speaking perfect Estonian, which is one of the hardest languages to learn. For some, speaking Russian is enough. Most of those from the northwestern part of the country live in Russian-speaking communities, consuming media, working and studying in Russian, so they do not really have any motivation to learn Estonian. A lot of my former classmates and friends speak a little Estonian so they can express themselves in a grocery store, but would hardly be able to read a book or watch a movie in Estonian.

I believe that learning the state language should be mandatory. I’ve visited different places and witnessed how migrants commit themselves to study the language of their new home country. But one thing is important to distinguish is when people change their country following their own choice, since it is an entirely different thing being a native resident and just happening to grow up speaking a different language.

Speaking Estonian is not yet a guarantee

Speaking the state language is not yet a guarantee to be fully integrated into Estonian society. Some public statements by our politicians are calling the Russian speaking population migrants and the Russian language as a language of occupiers. This might touch upon national feelings having negative consequences on integration and widen the gap between the two communities. It once again shows that Russian speakers cannot be fully accepted and accommodated into the Estonian society.

My generation is full of people without a motherland. I do not feel myself either Russian or Estonian. Estonia is my home country, the place where I was born, where my parents have lived for most of their life. But my country does not accept me. I’m not Russian either, because in order to be one I should consider Russia as my motherland. But, Russia is a foreign country for me. I have never lived there, do not possess a Russian passport, and do not know much about the place. The only link to Russia that I have is language and culture.

In a way, I fall somewhere in-between these two nationalities and cultures. I consider myself as a Russian-speaking Estonian. There is a big difference between Russians and Estonians here, but at the same time there is a discrepancy between people in Russia and Russian speakers in Estonia.

Giving up the Russian language and culture

Sometimes I feel unwelcome in the Estonian community. Despite the fact that I speak fluent Estonian, I studied for my bachelor’s degree in Estonian, served in the military here and hold an Estonian passport, I have noticed that people may avoid having an interaction with me if they have an ethnic Estonian as an alternative.

I think to be fully accepted, society expects us to give up the Russian language and culture because one’s native language to some extent determines the way you perceive the world around you. Quite often I feel more comfortable among Russian speakers, because I’m equal among them, while in the Estonian community I remain a foreigner.

I

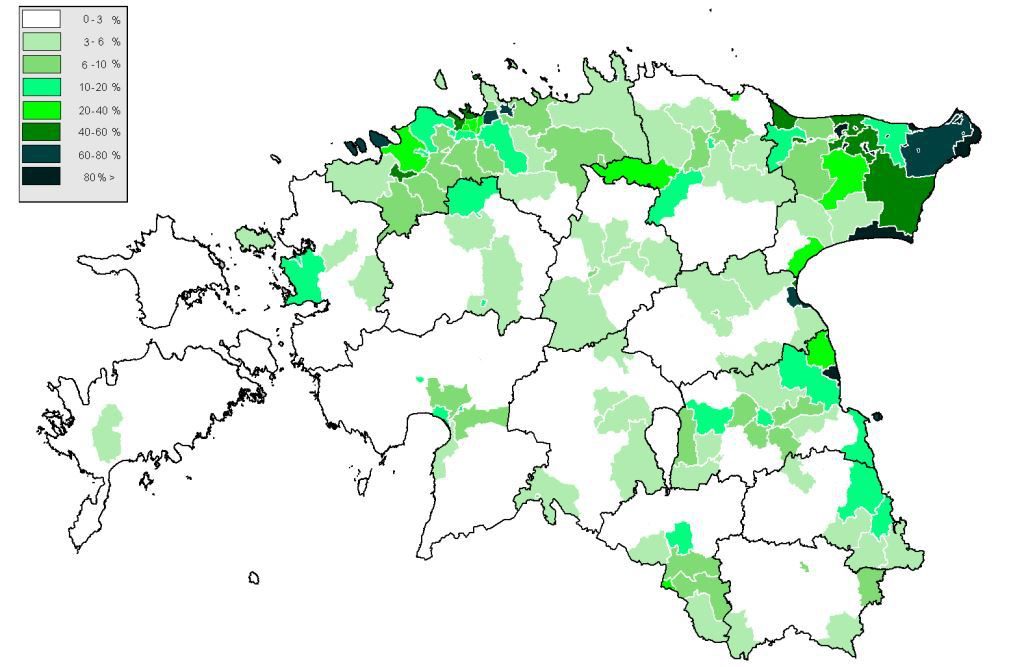

Cover: Distribution of the Russian language in Estonia according to data from the 2000 Estonian census. Please note that Nikita didn’t want to publish an image of himself or disclose his surname in public. Johan Skytte Institute of the University of Tartu and Estonian World have verified his identity and story.

Wish we knew the real identity of this author to allow a follow-up.

I get the message from “Nikita”, but unfortunately in these days of propaganda, fake news, and mis-direction, I have a hard time believing the vague things that were written.

Certain sentences don’t make sense. For example, the sentence: “I have noticed that people may avoid having an interaction with me if they have an ethnic Estonian as an alternative …” sounds more like a feeling of paranoia or lack of self worth by the author and not solid evidence of any discrimination.

I think it’s important to remember here that Nikita was INTERVIEWED as a part of a project. He didn’t just decide to write about problems he has experienced. A group of masters students who are all foreigners living in Estonia themselves decided to ask him some difficult questions and he answered honestly. If you have questions for the authors, there are links in the begining of the article with more specific information about the project and where the interviews come from.

Next article about Estonians in Ida Virumaa who are forced to learn Russian to communicate to these lazy whining Russians, please.

Nikita, why you hiding your face and name? I live in Kohtla -Järve, too. Rodina dolzno znat svoih geroev!

It’s not about totalitarian Estonia, not at all. It’s a great privilege that Nikita can make this statement anonymously, it shows that privacy works here very well. It’s more about that Estonia is a very little country, 2 handshakes and you know the president. Everybody would discuss him, send him letters with their “important” opinions. If I was him, would do the same. Would you open your face in his situation?. And besides.

“Cover: Distribution of the Russian language in Estonia according to data from the 2000 Estonian census. Please note that Nikita didn’t want to publish an image of himself or disclose his surname in public. Johan Skytte Institute of the University of Tartu and Estonian World have verified his identity and story.”

I am 55 years old and don’t write good English but I find strenght and honesty to come here and discuss the problems of Ida Virumaa. I feel here not welcome, but I still write. You can see my face in Facebook. I just don’t buy this story of Nikita. I can write here about russification and ethnic cleansing in Ida Virumaa, I can write how

What kind of opinion is “important” opinion and what kind of opinion is important. We must register in this site to comment but of “Nikita” from Kohtla-Järve can be anonymus because he is afraid of discussion, “letters”and different opinion? I am from Kohtla Järve too. I write my opinion here and people can discuss it and some don’t like it. I know I live in democratic country everybody is free to speak out.

What does this mean? “Rodina dolzno znat svoih geroev, “Nikita”

Nikita was interviewed by a group of Masters students who are all foreigners themselves. It is important to remember that he himself did not just decide to write anonymously about his problems. These students recognized a problem themselves and decided to address it. I think some of the comments here might be giving the world a worse impression than his honesty. All countries have problems and many have difficult historical situations with minorities. I understand there are historically sensitive issues in Estonia. A good impression for the world would be trying to solve a problem or find some common understanding without singling out specific individuals who bring them up.

I am very surprised with your attitude. You are speaking about absolute tolerance in our society but yet attacking this poor guy for opening up. I am sorry but such behaviour only shows that Russian speakers are not welcome in our society. We all live in this beatiful and beloved country so let’s make it great together by building a unique and strong society by including everyone irrespective of their mother tongue. Sometimes it’s better to discuss problems so we can understand and solve them rather than holding up to them till the boiling point.

Especially we solve problems with we publish anonymus opinions, No.

Welcome to the topic of “first generation immigrants” and the life between two cultures.

The topic that is much talked about in Sweden, Finland and Norway. Interesting to read something similar from Estonia.

Oh, Sanna. What first generation! In Kohtla Järve we have 2, 3 and 4 generation of Soviet/Russian immigrats. All “feel not welcome”.

Is it also true that those who don’t feel welcome in this society have also decided not to learn Estonian? It might be one of the main reasons.

I have couple of close friends who have russian parents, but they speak fluently Estonian. I feel that they are very much loved. Honestly, I have never even thought about it if they feel “welcome” in Estonia. The thing is that this question disappears after you have been part of the language.

It is simply because they are like other Estonians, no difference and the questions if they feel welcome or not becomes irrelevant. They are already Estonians, they part of Estonian family by speaking the language everybody understands.

In Scandinavia after the first generation who is born in their new homeland and finished the primary-school, these kids have picked up a new language. Thats how it is. If there are 4 generation of immigrants in Kohtla-Järve who choose not to learn the language of the country where their parents have chosen to live, its more like an attitude problem.

Or maybe its also problem of Estonians politics – the fact that primary public education can still be taken in Russian.

In most of the places in Scandinavian you have to pay a tuition to go to pricate school where you can get education in other languages.

You have to work for feeling welcome, to be integreted, to be equal in a way. I say it based on my own struggels while trying to integrate myself in Norway, trying to fit in, lear the language and feel equal. It not easy, but its the price that “feeling welcome” takes.

I also working in Norway and started to learn Norwegian when I was 49. All this complaining and whining about language and not welcome is rediculous. Most kids speak Estonian in Ida Virumaa and who dont just learn it. This whining is totally Soviet tradition!

Not sure how “whining” could be a Soviet tradition, considering that complaining about the government was generally prohibited in the USSR…

These people are not complaining about the Estonian govt, they are complaining about Estonians while choosing not to speak the language of the country they live in.

Who are “these people”?

Sanna: With all due respect, my father, who came to the US as a child refugee after WWII, was a 1st generation immigrant. The majority of “Russians” in Estonia are the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th generation that was transplanted in Estonia by Stalin. The 25% of the population they constitute is the result of Ethnic Cleansing, not immigration. They replaced the 25% of the Estonian population that was killed, sent to Siberia or forced into exile. I support Estonia’s policy of integration, but let us not forget the PROFOUND differences between how “Russians” are treated in Estonia now, and the 50+ years of torture, rape and pillage that Estonians endured under the Kremlin.

Imagine how can feel the few Estonian-speaking inhabitants in Kohtla-Järve, who survived the deportations of 1941 and 1949, and today have to “tolerate” such people, who don’t want either to study, or to leave and go to the largest country in the world, a few kilometres eastwards…

And how feels Estonian youth in Kohtla Järve now!I know young mother who went to gynecologist with her mother because doctor did not speak Estonian and the young woman spoke bad Russian! I can more such stories! And 1941 and 1949 were not that bad (hortible to say) worse was 60-70-80 mass immigration from Russia, this really killed old Ida Virumaa!

What I do not understand is the overall sense of grievance of the of the Russian-speaking inhabitants in Ida-Virumaa. Worldwide, there are many similar situations. Think, for example, the Ticino Canton in Switzerland, where 95% of the population is of Italian language, but they must suffer the cultural pressure of all the other cantons, where they speak German and French. Or think the Hungarian minorities which are located in Romania.

The Russians living in Estonia and Latvia can enjoy the advantage of being able to emigrate, when they want, in the largest state in the world, a few kilometers eastwards. Or they can choose to love the country where they live now, study the language (as well as Estonians had learned Russian from 1720 to 1918 and from 1944 to 1990) and try to do something new: for example develop the tourism or start business and cultural initiatives.

You can not spend your whole life thinking about what has been and what it should be.

Italian has official language status in Ticino and at the national level in Switzerland (even though Italian is the native language of just 7% of Switzerland’s population), so that’s very different to the situation of Russian in the Baltic states.

I think you’ll find that ethnic Hungarians in Romania have similar complaints and grievances to Baltic Russians. I’m not sure that the existence of similar situations in other parts of the world really makes the situation in the Baltic states any better.

And I don’t think it’s very reasonable to suggest anyone moves from the country where they’ve lived for decades (or even their whole life) to corrupt, authoritarian and economically inferior Russia.

Many problems are rooted in Russian community itself. Too often, local Russians still underestimate the trauma inflicted to Estonia by occupation and deportations, Sometimes, they mistake Russian cultural identity with loyalty to Putin’s Russia or even Soviet regime. Personally, I can hardly remember any cases of Russophobia here, after 2 years in country. Moreover, your attempts to speak Estonian language get usually very warm welcome. But Estonia is a northern country, so “warm” here doesn’t mean immediate handshakes, or invitation to drink together – like in, say, Georgia

EXACTLY.

Soviet (Russian predominately) brutal and repressive occupation. My grandfather was murdered by them and my mother fled in September 1944 as the ‘liberators’ approached Estonia. Estonians have a long memory.

Same here – we were forced out by the Nazis as the Russians invaded Tallinn in 1944 – I was 25 months old. My relatives were sent to Siberia – one was 18 months old at the time!!

Cry me an effin’ river…

How do the actions of Stalin have any importance to how we treat russians today? There is no logical connection there. Russians living in estonia mostly did not deport anyone.

Doesn’t make any difference in terms of meaning of the article that the writer is anonymus. You JUST want to know who the writer is… because….(no reason…you are curious). Does not make any difference who the writer is.

Saying Stalin deported estonians and treated them badly has zero logical connection to most russians in estonia now. The rape, pillage, killing, deportation – anything you can think of, does not connect to most of the russians living here now. So stop talking about what Stalin did in connection with russians in Estonia now.

What does language have to do with how you treat people.

Soviet russia was a brutal regime. Sure. You are right. Thanks for the reminder. Why are you writing that here?

SIIM – the problem is exactly that so-called ethnic Russians in Estonia do not know Estonian’s soviet history as they and their parents and grandparents were fed lies so they do not understand why there is such bitterness towards Russians, & especially those in Estonia who do not want to integrate. Perhaps you are even too young to know whatg was going on in Estonia fro 1914 to even 1990 .

Let’s start with this article’s use of the word “motherland” – there you have made a choice to not be Estonian already – Estonia is an Estonian’s “fatherland” – it’s made quite clear in the national anthem. Secondly, how a person “feels”i s their choce, not some outsider’s choice. I was born in Estonia, was forced out at the age of 2, lived in Germany, the USA, Finland and Australia.I ‘m an Australian citizen, have lived in Australia most of my life, have an Australian accent but I FEEL Estonian, and that’s that!

Dear Nikita, I am sorry that You are feeling that way. But to Your comfort I must say that whole first generation of descendants from immigrants are feeling like this. Not only in Estonia but in the whole world. But as You said You still feel unwelcome sometimes it is not because You are Russian. Friendship with Estonians has many layers. Most of us are calling friends only these people with whom we have been friends since childhood or from midschool time. The others are coworkers, acquaintances, “someone I know” etc. And yes..deep in our hearts we are very precautius towards everything and everyone who is not like us..it is our nature I guess. Maybe Your feeling of being unwelcome is coming from Russian culture backround where is much more easier to find a common language between people around You.. just look on the situation from that perspective. And never be concerned what primitive people say about “bad dids of Russians” they will hold the grudge towards You until they die. To You Nikita I wish the best..be brave, do not let yourself intimidate by anyone. There will be always people who think that You are not good or talented enough to achive Your goals or fulfill Your dreams. So stop being sorry for yourself.

Best regards…

Sirje

This is an interesting interview. I am a Briton in Estonia and not at all surprised by Nikita’s experiences. I am also not surprised by the passive aggressive nature of “Sirje Malmet”. Either she is very naiive, or is funded by the Kremlin. It would not suprise me in the slightest if Russia funds both pro-Kremlin, as well as pro-Estonian groups (accounts such as Sirje’s) in order to exacerbate the divide. Well done on playing into their hands. Like it or not, these are your people. If anything does happen in Estonia, it will be because of the apathy and antagonism exhibited by you and your ilk.