In a world where music often speaks louder than words, Arvo Pärt’s compositions resonate with profound, almost spiritual clarity, and his minimalist approach, characterised by hauntingly beautiful harmonies and meditative silence, redefines the classical genre and invites listeners into an intimate dialogue of love and transcendence; here is a visual retrospective of Pärt through the years.

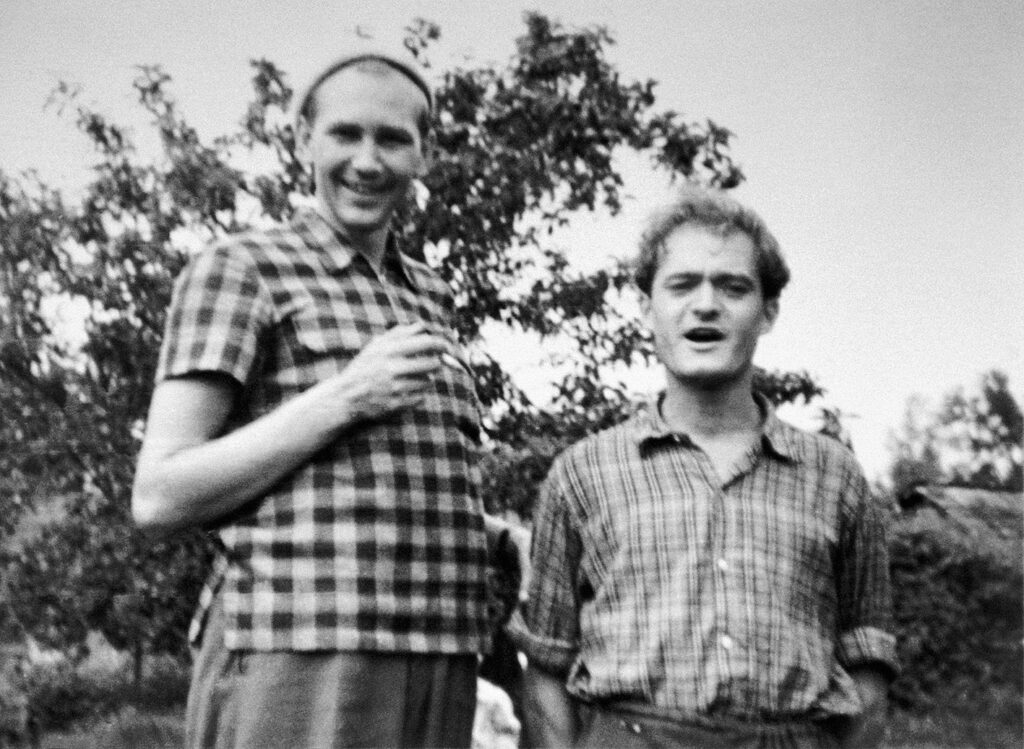

Arvo Pärt was born on 11 September 1935, in the Estonian provincial town of Paide, but his parents separated and, before the onset of the war, the mother and son moved to Rakvere. The childhood and early youth of the future composer were spent in the tranquil milieu of that small town. When he started school, the Germans were still in charge in Estonia, but when he commenced his piano lessons at the age of nine, life was lived according to the directions set by the Soviet occupation regime.

Those were restless and anxious times, and left a stamp on many people. When, on Stalin’s command, tens of thousands of people were deported from Estonia to Siberia, Pärt’s close relatives were among them. This left a thorn in his soul and a strong sense of revulsion towards the foreign powers.

The young lad attended school, fooled around with his friends and became fixated on films screened in the local cinema. Music entered his life bit by bit, but from a certain point onwards it overshadowed everything else.

The radio became the focal point of his life: after all it played classical music. On Fridays, live concerts were transmitted and the young Pärt biked to the central square of the town, which had a loudspeaker attached to a post. He used to circle around that post until the end of the concerts. Today the sculpture of a boy with a bicycle on the central square in Rakvere is reminiscent of those occasions.

In the draughts of power and spirit

After graduating from school, Pärt went to Tallinn, where the best Estonian musicians and teachers worked. His wish was to become a composer. By then the city had been cleaned up of war ruins, Stalin was dead and a whiff of new-born hope was floating in the air.

In the late 1950s, Pärt’s early works first attracted attention in Tallinn, where they were approved of by older colleagues in the Estonian Union of Composers, and subsequently in Moscow. The times favoured young energy and the socialist society tried to guide it in the “right” direction.

Culture also played a role in the bloodless battles of the Cold War, where competing ideologies tried to prove their supremacy to the masses on the other side. Sometimes it worked. In this confrontation, every talent was seen as a future warrior and Pärt was favoured.

But in Estonia, on the border of the huge red empire, the Iron Curtain was weaker and thus the echoes of modern Western composition techniques could be heard. Pärt became fascinated by them, the more so as they provided the opportunity to express his defiance of the regime. Problems soon developed, as the environment in which Pärt lived considered Western influences to be enemies. Defiance was unacceptable.

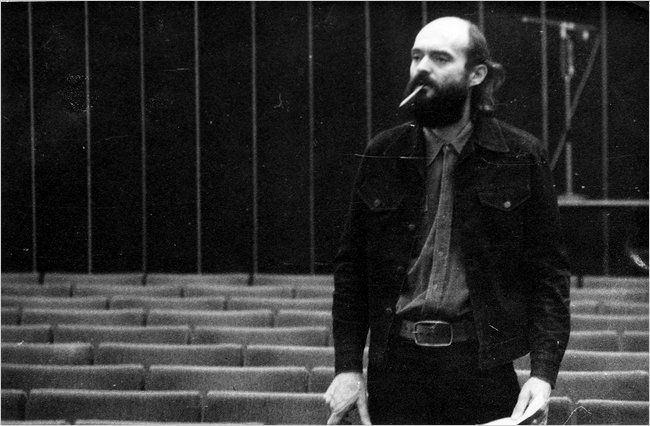

Ever since his student-time orchestral work, “Nekrolog” (1960), strong pro and contra draughts had been blowing across his path as a Soviet composer. He was praised, only to be criticised later, persecuted and favoured. Audiences were keen on his music, but the officials had their doubts.

Working as a sound engineer and a recording director at the Estonian Radio in the 1960s taught him to listen to the fine nuances of sounds. This job probably also gave him a crash course in the psychology of musicians, which later helped him significantly in making his own special world of sound audible.

Years later, Pärt said his crooked road of searching for beauty, purity and truth – of seeking God – began in the 1960s. It was the course he chose. Even as a young man, he had high ideals and the intuitive sense that making compromises could lead to losing everything.

Searching for beauty, purity and truth

Around 1968, when there was anxiety throughout the world, Pärt lost faith in the contrasts and oppositions of his music. He began to look for a new shape and expression for sounds. This was a situation in which he had a general sense of what he wanted to say, but he had not yet found the right words, the shapes of sentences and rhythms of speech to express it. Pärt turned to music from earlier centuries and tried to find a way to translate the tranquillity and clarity of that old music into his own language.

This was the great turn that changed his life, both internally and externally. He got married for the second time and moved, living a modest life in a dismal housing estate on the outskirts of Tallinn. The searching years were difficult and those solitary attempts often brought only disappointments. His wife, Nora Pärt, has recalled witnessing her husband almost losing faith and seemingly considering the idea of giving up trying to be a composer.

Then came the spark that changed it all. Born one February morning in 1976, the piano piece, “Für Alina”, opened a new door and light poured in. Discovering his own unique style – tintinnabuli – was a new start for Pärt in music, but the direction of his search remained the same. Tintinnabuli is often mentioned when talking about Pärt’s music. It has been called a method of composing, a unique style and a way of thinking.

There is no simple and clear definition, but many explanations have been offered. Interest in those explanations has grown in parallel with the interest in Pärt’s music all around the world. We do not know if this interest has reached its peak, but we do know for a fact that the music of this Estonian composer has been the most performed contemporary music in the world for several years running.

Reaching out

The call in his music has been slow to reach people, just as the music itself has a slow tempo. When Pärt left the Soviet Union in 1980 and moved to Vienna with his family, there was nothing positive waiting for him there. The foreign environment made him withdraw ever more into himself and the spiritual world of his music was just as ill-suited for that environment as for the one he had left behind. He wasn’t yet aware of the fact that by chance, a particular German had listened to his music on a car radio in the same year, 1980.

The German in question was Manfred Eicher, the founder of ECM Records. Eichner later recalled that he became so excited that he stopped his car and knew there and then that he wanted to release an album with Pärt’s music. The two men met in Vienna and inspired by the Estonian composer, Eicher established the “New Series” imprint under ECM, the label he founded in Munich in 1969.

When Manfred Eicher and ECM released “Tabula Rasa” in the autumn of 1984, it was a real statement and marked another significant turning point for Pärt. Eicher later said he believed the main piece on the album changed the awareness of music throughout the world in the late 1980s. This may sound a bit pretentious, but many people agree.

The story released by the American press, which has been cited on many occasions, tells of a journalist seeing young men with AIDS, waiting for death in a refugee centre, who listened to Pärt’s “Tabula Rasa” again and again. The sounds must have incorporated something very significant for people dealing with such a serious situation.

All is one

Later, many articles asked what it was that pulled people from different parts of the world, people with different skin colours, who spoke different languages and had diverse world-views, towards Pärt’s music. Many answers have been proposed and, at the same time, his music has been criticised for being light and flirting with listeners. Such comments have come from representatives of modernist music. Such reactions may have been caused by the composer’s clear desire to be on the same wavelength as his listeners, not to tire their perception with sound tangles and structures pushing their limits.

On the cover notes of the album “Tabula Rasa”, there is a beautiful comment by the composer in which he compares his music to white light, which after piercing the prism of the listener acquires different shades. From this angle, all of the elements in this music meet each other: the composer, the musicians and the audience. “Me” and “they” become “us” and things find their natural place. There is balance and order. At least in the ideal world.

Arvo Pärt has said very little to explain his clear and simple music, which aims for unity. The fewer the words, the larger the space to interpret the music. “All is one” and “one and one makes one” are two of the most typical descriptions. The first sums up his worldview generally, and the second describes the unity of the polarities of tintinnabuli.

Music crossing borders

The universe of this music is spiritual and the sounds can be seen as “religious” in a way. People often wonder why Pärt’s music communicates with people regardless of their religious confession or the lack of it, regardless of age or ethnicity. Perhaps he has been able to translate something very human into sound that crosses the borders normally separating people. We do not know; we can only accept this explanation or offer our own answers.

What we certainly do know is that Pärt’s name has become very influential. It stands for music which many people love. Tranquillity, sadness and selfless love emanate from the sounds of that music. It consoles and gives strength to listeners around the world – from Italy to Iran, from Belgium to Brazil, from Ukraine to the US.