Ten Estonian contemporary artists, acting as accidental anthropologists, have paid special attention to the side effects of the modern extractive industries in Estonia; their exhibition, “Life in Decline”, at the former administrative building of the mine “Estonia” in the country’s Ida-Viru County, displays artworks that function as analytical artefacts.

Decline is hardly an alien phenomenon. We all know something, someone, somewhere rusting, ageing or growing backwards. Nevertheless, there are many things happening in a state of breakdown and decline; there is an intense social, cognitive and material activity in deteriorating infrastructures, houses, roads, skills etc.

Indeed, breakdown can also be ordinary and normal, as a condition in which recovery has not been achieved, yet many things continue to go on in the meantime. This is because what becomes a wound can also continue to be a place in which to live.

In the exhibition “Life in Decline”, the curators have tried to open up “decline” in its multiple facets, paying special attention to the side effects of the modern extractive industries in Estonia’s Ida-Viru County. Ten Estonian contemporary artists, here acting as accidental anthropologists, have been paying special attention to the side effects of the modern extractive industries in Ida-Virumaa to create artworks that function as analytical artefacts.

In this interdisciplinary project, the curators propose looking at the different ways of inhabiting decline and observing how drained ecologies have been produced after a prolonged and systematic harm. Indeed, decline can be presented as a problem of thought, a challenge of understanding, something hard to put into words.

According to the organisers, disrepair can be also considered a form of peripherality and dispossession, a situation of being excluded from collectives that previously provided social and economic frames. Brokenness reveals fragile relations between people, and that material injuries aggravate immaterial ones. Brokenness and decline have traditionally been seen as a pervasive condition of disarray and disorder, an offence against the neat and tidy. Any breakage seems to put an end to a time and to an order, however it might last in time, expressing different stages and socio-material manifestations.

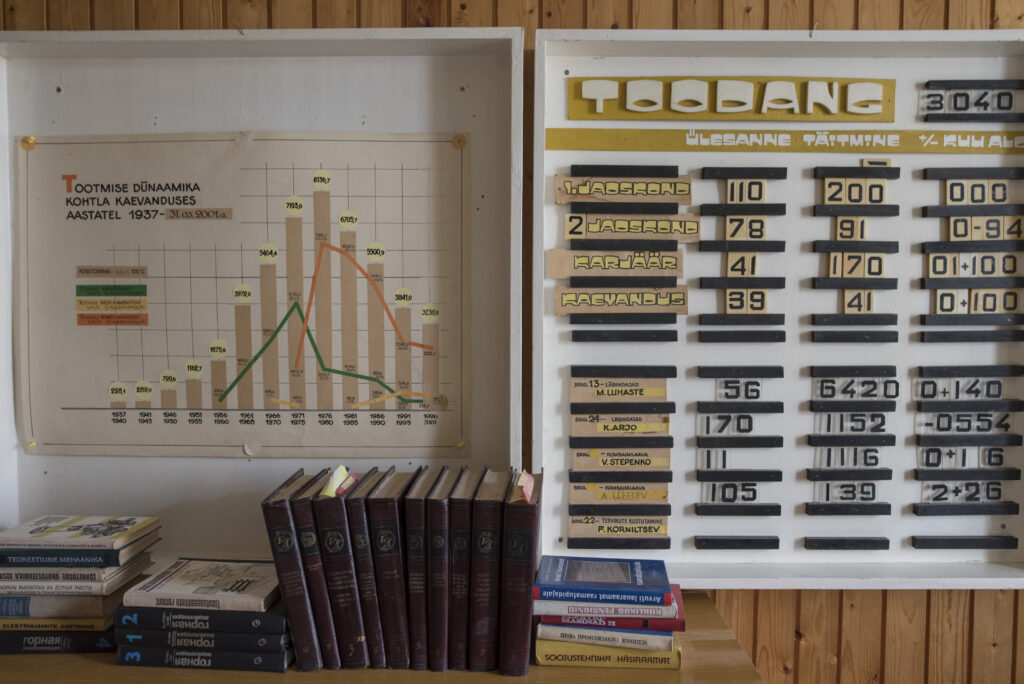

The contemporary art exhibition, “Life in Decline”, is currently taking place in the former administrative building, the so called White House, of the mine “Estonia” – the only mine in which Estonian was the lingua franca during the Soviet occupation. In this area, the open-pit industrial extraction started in 1919. Then, thousands of miners moved to the region, and a railway station and processing factories were rapidly built.

Nowadays, everywhere you look you can find remains of infrastructural systems of the Soviet past, derelict sites that stand where heavy industry had once flourished. Here are five examples of the works included in the exhibition:

Sandra Kosorotova, “Sore”

What plants actually grow in exhausted ecologies?

Weeds in a garden or on a lawn are often associated with a lack of care and control. Likewise, they are present on wastelands, thriving where no other plants can survive, yet acting as a natural plaster to the wounds of the land. However, a weed refers to a plant that is not wanted in human-controlled settings. That’s the reason why the word “weed” is applied pejoratively to species outside the plant kingdom that are undesirable in a particular place, but manage to survive and reproduce even in unwelcoming and harsh environments. In this sense, it has also been applied to humans: Nazis would speak of certain ethnicities as “weeds”.

Because of her Russian background, the artist has often felt herself as a “weed”. In Estonia, one of the most hated weeds is “Bunis orientalis”, which is considered an invasive species. It was brought to Europe by Russian soldiers during the Crimean war (1853–56), who added this weed to their horse feed. Here, it was first noticed in Rakvere, and hence the folk name “Carrion from Rakvere” (“Rakvere raibe” in Estonian). According to a decree issued in 1939, the plant should be destroyed if encountered.

For this installation, the artist transplanted several found weeds in and around the exhibition spaces and also used them to dye textile that is now displayed in the laundry room of the white building.

Edith Karlson, “Another short story”

This installation, composed of the skeleton of a seal, greenhouse plastic and polyester vax represents the actual relationship between animals and people, showing how exhausted the modern belief is that we could impose ourselves on nature.

Here, the animal is present in its pure deadness – a skeleton – while the human is represented as an elegant dominator – through a plastic jacket, insinuating the power of a uniform. Its transparency refers to the tale of the Emperor’s New Clothes, where a great parade ends up with the realisation that all was a hoax. While calls continue to be heard for an intensification of human mastery and extractive powers, this work invites a re-articulation of the relationship between nature and humanity.

Anne Rudanovski, “The work of time”

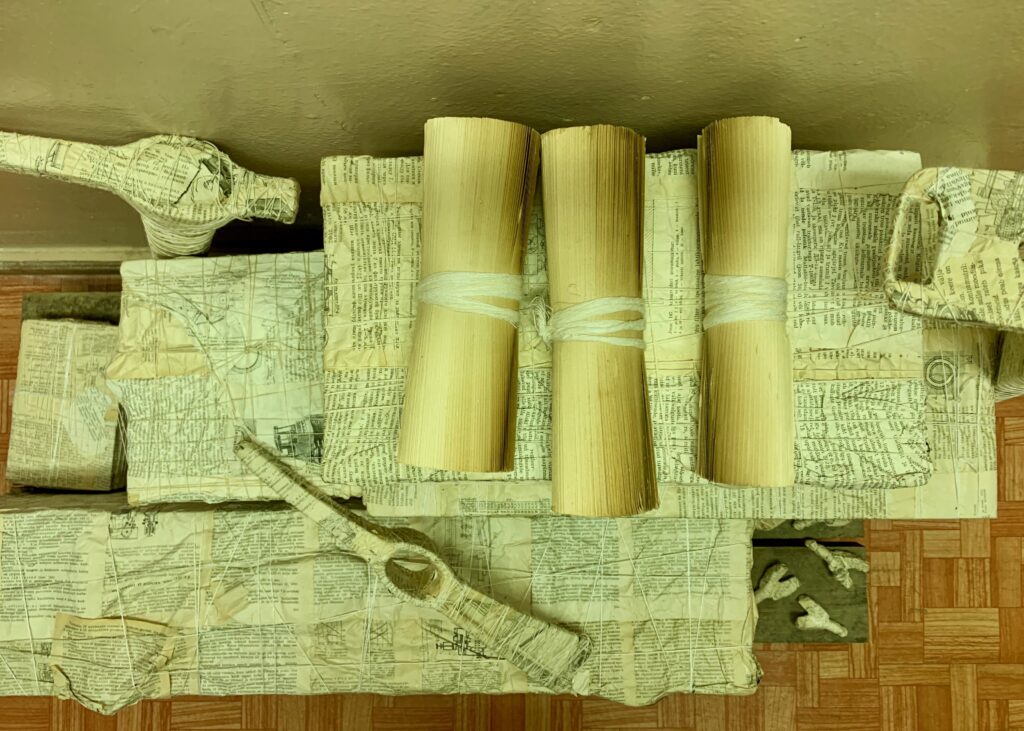

After coming to the end of the corridor, the visitor encounters the archive of the Kohtla mine, a telecommunications room and a space for storing the measuring technologies of Soviet engineers. However, they all are affected by the work of time, showing a strange, museistic obsolescence. The corridor itself, as an intermediate stage, prepares the visitor for the liminal experience enhanced by the artist.

In the rooms, here and there, the visitor can see things that are packed and ready to be sent elsewhere. They are wrapped in pages torn out from old industrial manuals in Estonian and Russian. Still, a sharp eye would be capable of reading the instructions, studying the drawings, and following the past calculations in the wrinkled surfaces. Some packages are incomprehensibly festive; some others evoke a sense of holiness, or just seem to be abandoned.

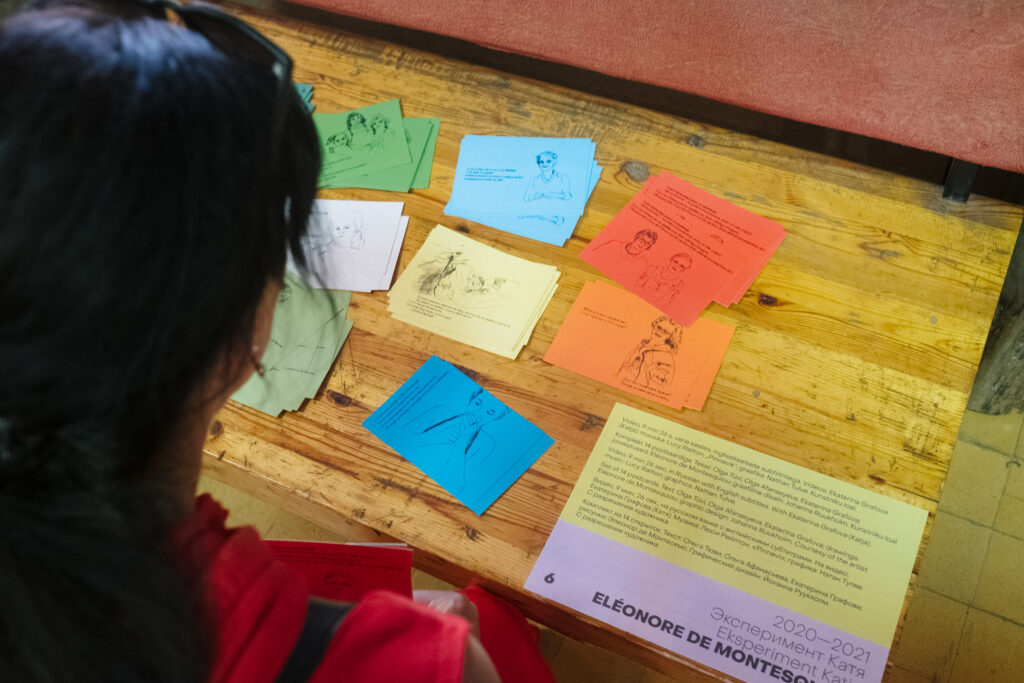

Eléonore de Montesquiou, “Experiment Katja”

“I finally understand when a new experiment begins”. This installation is composed of a film and a series of postcards in which the artist reflects on the multiple gender struggles taking place in the region.

The main character of the film, Katja, was born in 1992. Her generation went through multiple social experiments while building the Republic of Estonia. She feels neither rooted in Estonia nor Russia. In the meantime, Katja tries to carve her own personal way and betwixt identity, fallen between two worlds, floating. From “Little Red Riding Hood” to different attempts at trial and error, the film conveys the anxieties of this transitional generation.

John Grzinich, “Geofractions”

This soundscape composition gives a sensory experience of the processes and infrastructure of oil shale extraction and energy use that is often hidden from the public. While we have grown familiar with the visual language of mined landscapes, how often are we able to immerse ourselves into extractive processes through the auditory?

The “journey” of such processes takes us from underground mining and transport to the residual waste that generates and sustains the energy infrastructure we depend on. The current outcome is part of a long-term sensorial survey of Ida-Virumaa that started in 2009.

The installation work is based on a scale model of the thin geological oil shale layer made in the shape of this region. The symbolic surface rests on a base of speakers and transducers (sonic shakers), which will induce vibrations from underneath. The 100-minute-long piece represents one minute for every year since the mining industry was founded here.

Altering the limits of what is possible in social research

This exhibition seeks to alter the limits of what is possible in social research while emphasising the gesture of researching with, and not just of and for. It assumes that we can interfere within our object of study without creating any harm or assume that we are intrinsically creating data or misrepresenting the people we’re studying.

In this sense, we approach the exhibition not as an endpoint, but as a research method and/or device. The field becomes then a site of experimentation and co-creation – by building horizontal open-ended relations with epistemic partners (formerly taken as just informants).

The fact that, in some cases, my epistemic partners might be more analytically capable than me (the curator and ethnographer) challenges the traditional principles of anthropological research developed in a period when the European (or Western-educated) white men travelled far to gather data about native informants – merely approached as knowledge-holders. This take on social research is interventionist and demands from the anthropologists to be an active participant in the construction of the field, not just observant. By doing that, we decentred the role of the ethnographer, redistributing roles, responsibilities and analytical capacity.

By using the exhibition as a research method, we aimed to understand what is going on in Eastern Estonia. Here, decline has been more severe and long-term than in the rest of the country. Grounds were affected by the intensive mining and extractive activity of Soviet modernisation.

Then, industries were affected by post-socialist economic development – since many were too large, used obsolete technology, or were of no interest to new, global investors and the state. To this, we have to add a lasting stigmatisation from the national media, creating a sense of regional disposability and articulating grammars of exclusion.

One of the things we learnt is that the diverse key locations of Ida-Virumaa are very different from each other, and not always interconnected. There we can find Narva, the historical and geopolitical centre, but also Kohtla-Järve, Sillamäe, Oru, north Peipsi, Kiviõli, as well as the new administrative centre, Jõhvi.

In short, two implications of this art project are that by intervening and experimenting in the field (following design and art practices) we can enhance the contemporary ambitions of anthropology. The second implication is that exhibitions do not only serve to communicate findings, but they can also participate in ongoing research as spaces for knowledge-in-the-making, whereby several analytical artefacts are assembled, discussions are provoked and meaningful relations are intensified.

The exhibition, “Life in Decline”, is open until 3 October at the Estonian Mining Museum in Kohtla-Nõmme.

Cover: The exhibition, “Life in Decline”, is open at the Estonian Mining Museum. Photo by Laura Kuusk.