Once a symbol of culture in Tallinn, Linnahall now stands as a crumbling monument to Soviet ambition and post-independence uncertainty; built for the 1980 Moscow Olympics, the vast structure was meant to connect the Estonian capital to the sea – but more than four decades on, its future remains unresolved.

Estonian World had a rare chance to step inside the iconic Linnahall, joining an English-language tour led by the Estonian Centre for Architecture. Slipping behind its usually locked doors, we wandered through the vast, echoing interior.

Dust hung in the air, footsteps ricocheted off bare concrete, and a quiet awe settled over us as we traced its layered past – from proud Soviet monument to eerie post-apocalyptic film set. It felt less like a tour, more like time travel.

Linnahall’s complex legacy

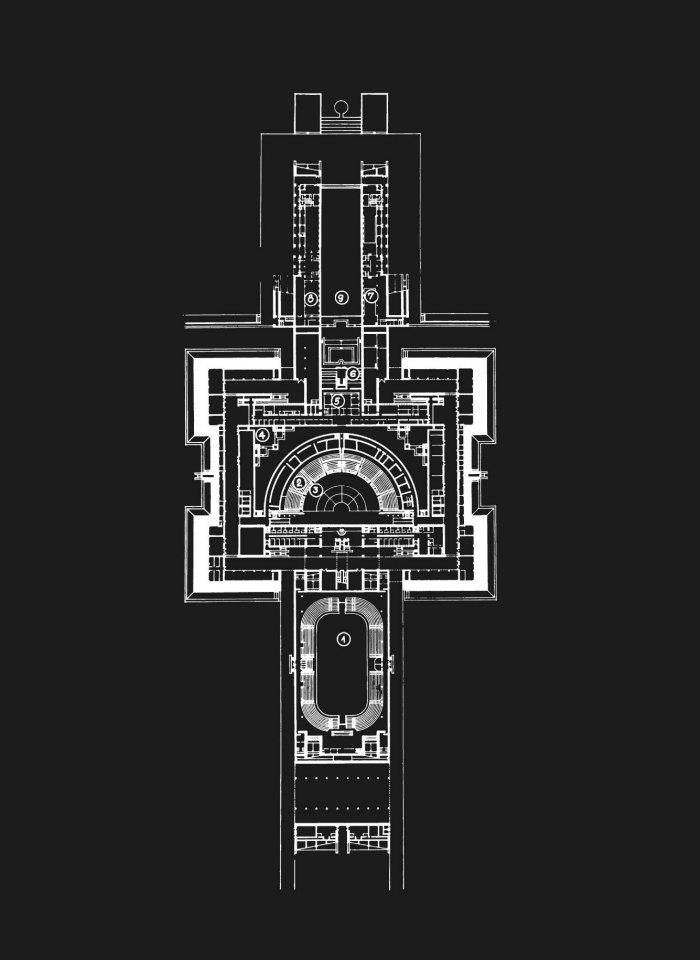

Originally commissioned to host the sailing events of the 1980 Moscow Olympics – held in Tallinn, as the Soviet capital lacked access to the sea – Linnahall was conceived as more than a sports venue. It was a bold architectural gesture, a physical and symbolic bridge between the city’s historic centre and the Baltic shore. The original plans included a lush public park surrounding the structure, but budget cuts and time pressure meant that vision was never fully realised.

Built in the imposing Soviet Brutalist style – all raw concrete, monumental scale and geometric severity – Linnahall stood as a testament to its time. The term “Brutalism” derives from the French béton brut, or “raw concrete”, a concept popularised by Le Corbusier and embraced during the post-war reconstruction of cities around the world.

But Linnahall wasn’t just an Olympic leftover. At its height, it pulsed with life. The 4,200-seat concert hall – complete with an ice rink – became a cornerstone of Tallinn’s cultural scene. From the 1980s onwards, it hosted everything from local legends to international acts like Duran Duran. Bars and restaurants sprang up in and around the complex, turning it into a buzzing hub where music, skating and conversation carried on late into the night.

Yet for all its ambition – and its use of high-quality materials like local limestone – Linnahall was a paradox: part showcase, part shortcut. Some sections were solid and striking; others, hastily finished and barely held together. Even at its peak, it bore the hallmarks of a grand project rushed to meet a deadline. One infamous example: the amphitheatre stage, which was intended as a temporary fixture but remained in use throughout. During one circus rehearsal, a hippopotamus crashed through it – fortunately, no one was hurt.

In 1997, Linnahall was added to Estonia’s list of protected buildings. While the designation spared it from demolition, it also complicated restoration efforts. Despite its heritage status, little in the way of maintenance was ever carried out. Years of neglect and mismanagement led to its closure on 1 January 2010. Hopes for renovation faltered after the redevelopment company became embroiled in a corruption scandal in Hungary – and no new investor has stepped in since.

Linnahall a ghost of its former self

Today, the once-vibrant venue is largely sealed off. The interior remains closed, though a handful of residents still occupy parts of the building – a reflection of Tallinn’s surging housing costs. One of the few active spaces is the Linnahall recording studio, which continues to draw artists. But maintenance is limited to these pockets of use, while the rest of the complex slips further into decay.

In recent years, Linnahall has flickered back into the spotlight – on film, if not in real life. In 2020, director Christopher Nolan used the site as a stand-in for the “Kyiv Opera House” in Tenet. For a brief moment, the long-abandoned concert hall was revived, complete with extras and dramatic set lighting. On screen, Linnahall appears bustling and alive – a striking reimagining, though one far removed from its original identity.

Outside, the venue still draws a steady stream of skaters, sunset-watchers and urban explorers – all lured by its eerie charm and monumental scale, even as the structure crumbles around them. In Tallinn, Linnahall has become a subject of heated debate: should it be restored, repurposed, or torn down altogether?

Over the years, Linnahall has inspired no shortage of reinvention schemes – from green public parks to glossy shopping centres. The latest proposal, unveiled this year by the Tallinn City Property Department, envisions transforming the site into a modern event centre and re-establishing its link between the city and the sea. The plan includes cutting car traffic, expanding pedestrian areas and restoring Linnahall’s role in Tallinn’s urban fabric.

Under the plan, a separate plot will be reserved for Linnahall itself, earmarked for a landmark cultural venue – potentially a concert hall, opera house, museum or library. Another adjacent plot will support port-related commercial activity, including a winter swimming centre and a small harbour for travel between Aegna and Naissaar, with the option of adding a marina.

The case for saving Linnahall now

Grete Tiigiste, architectural historian and curator of Linnahall Forever as well as the current exhibition Sailing Forward: How the 1980 Olympic Regatta Shaped Tallinn at the Estonian Museum of Architecture, believes Linnahall’s future must be shaped with – and for – the public. “Linnahall should, of course, be restored and renovated,” she says. “But the best way to use it would be to give it back to the citizens – along with its function.”

She imagines a cultural hive, not unlike Tallinn’s creative district of Telliskivi — a place where artists work, cafés and restaurants buzz with life, and the city’s energy flows freely. “Linnahall is so massive – it has over 100 rooms – so it’s possible to adapt them,” she says. For Tiigiste, there’s an urgent need for more free cultural spaces in the city, especially in winter: places where young people can gather without the pressure to spend money.

While Linnahall is legally protected as a heritage site, Tiigiste notes that the heritage board is open to flexible, forward-looking solutions. Encouragingly, researchers have confirmed that the building’s foundation is structurally sound. “It’s the rest that needs renovation,” she says, pointing to the long-abandoned ice rink as one of the most neglected areas.

Despite its solid bones, Tiigiste argues that Linnahall’s decline has less to do with architecture and more with poor stewardship. “The city hasn’t been a very good owner – they haven’t taken basic care of it,” she says. After Estonia regained independence in the 1990s, public funding dried up. “Everything was privatised, and the city hoped Linnahall would generate enough revenue to sustain itself. But it didn’t work out like that.”

Today, the debate over Linnahall’s fate has reached a critical juncture. One thing is clear: doing nothing is no longer an option. With each passing year, the structure deteriorates further – and the cost of revival climbs. Whether Tallinn chooses to restore, repurpose or radically reimagine Linnahall, the time to act is now.