The Estonian Genome Project – a national super-science project where gene samples from over 52,000 people were collected, comprising about 5% of the population of Estonia – is now, 17 years after the project began, offering personal feedback to people who donated their blood and information.

Through the hardships

It was in 2001 when the local scientists came up with the ambitious plan to collect, record and thoroughly decode the genetic information of Estonians. They hoped the project would lead to scientific discoveries and help create more precise medications. In 2007, the state became the project’s main financer and the Estonian Genome Centre was merged with the University of Tartu. Sample collecting began again, celebrities were hired to raise awareness about the project and the topic of donating genetic information even appeared in the popular Estonian soap opera, “Õnne 13”.

The Estonian Genome Centre got a new building with the monetary support from the European Union; new, state-of-the-art technology; and also lured back some of the scientists who had left Estonia. By the end of 2010, all the samples had been collected. What distinguishes this biobank from others in the world is that, in Estonia, the data collected did not involve only those who were ill, but it also offered a cross-sectional genetic view of the society.

The youngest donor was 18 years old and the oldest 104. Each participant donated about 40 millilitres (1.4 fl oz) of blood and completed a questionnaire of 300 questions in which everything was mapped – from eating habits and level of physical activity to the reasons for the deaths of ancestors. Five per cent of the population was involved in this project, which is the second highest number in the world – right after Iceland.

After the samples were collected, the scientists focused on research. The data from the donors was used in hundreds of cooperation projects around the world, where the impact of genes was researched in various fields – from coffee-drinking habits and intellectual capacities to schizophrenia and other hereditary illnesses. The genome project had the most internationally cited Estonian scientists involved in it.

Finally, after the 17-year-long roller-coaster ride, the day has arrived: donors will start getting something back. These 52,235 people who offered their information will be able to inquire about the results starting in autumn. “They are the avant garde of society who agreed 17 years ago to donate their genes without actually knowing if the project would succeed. They hoped that there would be some use of it,” Andres Metspalu, the director of the Estonian Genome Centre, said.

Personal gene map

Take, for example, a local male journalist who was one of the donors. There are many important data points on the gene map of him, providing hints about risks of hereditary diseases, as well as many other ailments. Neeme Tõnisson, a medical geneticist, tells him that by the age of 51, his risk of getting diabetes is 4.4 per cent. Losing seven kilogrammes (15 lbs) of body weight would cut this risk in half.

So far, science hasn’t reached the point where the gene map could offer information about all the possible hereditary illnesses. “We could definitely spot the risks of many various illnesses, but there’s also the question of what people can do about it by themselves,” Tõnisson concluded.

One could receive information about hereditary heart diseases, type 2 diabetes, glaucoma, breast cancer and hereditary risks of bad cholesterol, but also about the risks for overeating or getting addicted to smoking. In addition to that, in some cases, the efficacy of a medicine could be detected.

“Antidepressants, painkillers, the drugs for preventing cardiovascular diseases – all of these are linked to specific genes, so we could give really specific suggestions,” Lili Milani, a senior researcher at the Genome Centre, explained.

The project doesn’t offer answers to “spicy” questions that could reveal, for example, the potential infidelity of a partner. One can get feedback about situations when the person himself is well, but, in certain circumstances, his or her children might be at risk. “People carry alleles. If one chromosome is mutated and you marry someone who has the same mutation, you have quite a substantial risk of having a child who will be ill – 25%,” Andres Metspalu said, as an example.

The right of not knowing

According to Metspalu, genetic research is a tool, just like an X-ray or tomography. Still, there’s one big difference – genes make it possible to predict the future. The topic is surely a delicate one. Is it even right to tell a person they have a great likelihood of a serious disease?

“Globally, there has been an ethical discussion going on for a long time about whether we should perform analyses on healthy people and give the results back to them in some way,” Tõnisson said. According to him, no one should be forced to get information about the diseases threatening them. “We know that there aren’t many people with such a high risk of getting some illness in the future. It might be one person out of a hundred, or three people out of a hundred, but they have to have the right to decide if they want to know this information or not,” he explained.

What will the future bring?

According to Metspalu, it’s all just a beginning, and we’ll be able to find problematic combinations from those gene maps hand in hand with our ability to detect them. “There are about 700,000 different genome markers we can study from one gene map. So we’ll return to it in a year and look at what we can understand then that we don’t understand now,” Milani added.

The Estonian Genome Centre project has cost €12 million so far. The greatest benefit, in addition to the new knowledge, will be a reduction in health-care costs. When there is an ability to foresee risks, people don’t get ill that unexpectedly and the prevention and/or early treatment might not cost as much. “We must see medical projects of this kind not as expenses, but as investments in our future,” Metspalu emphasised.

I

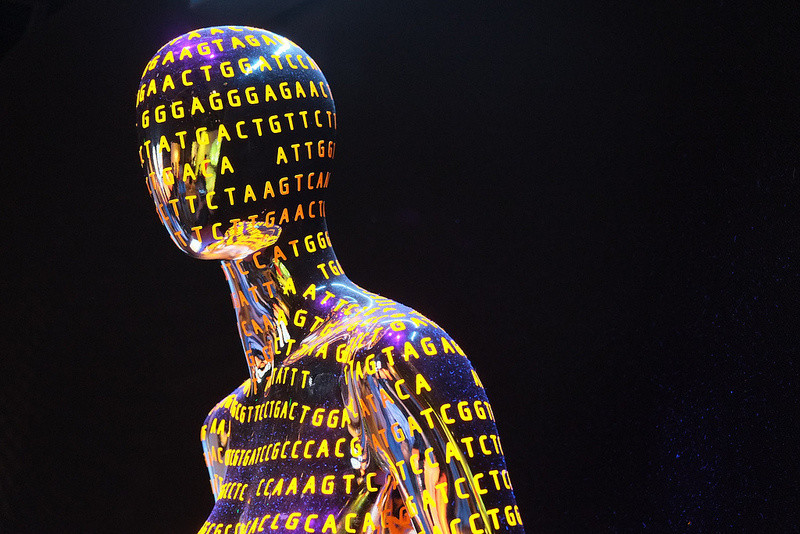

This story first aired on the Estonian Television’s programme “Pealtnägija” and was published first in English by the University of Tartu blog. Cover image is illustrative (Richard Ricciardi / Flickr.)