In the early twentieth century Estonian artist Ants Laikmaa created beautiful portraits of Ethiopians and North Africans, while still developing a distinct Estonian art. The range of his portraiture reveals the tolerance and acceptance in Estonia over a century ago.

Estonia has always been multicultural, yet recent debates about EU migration quotas tend to suggest otherwise. “We do not want to become minorities in our own country!” many claim. Estonia may seem to be relatively homogenous in 2015, but immigrants are nothing new to the country. In fact, we have visual documentation of multiculturalism in Estonia from over one hundred years ago. One of the most stunning examples comes from a series of portraits painted by the Estonian artist, Ants Laikmaa (1866-1942).

Capturing the vitality of the people

Laikmaa was part of a seminal group of Estonian artists who sought to create a distinctly Estonian art in the early twentieth century. In the era of the Young Estonia movement, the art of Laikmaa and his colleagues aimed to further Estonian high culture.

Part of this project included elegant portraits of the Estonian intelligentsia, such as this painting depicting the young poetess Marie Under, among others.

Part of this project included elegant portraits of the Estonian intelligentsia, such as this painting depicting the young poetess Marie Under, among others.

Originally from the Haapsalu region, Laikmaa was also interested in Estonian peasants, their traditions and their folk clothing. In elevating Estonian peasants as worthy subjects of portrait paintings – a subject long considered appropriate only for the elite – Laikmaa captured the vitality of the Estonian people.

Works such as Girl from Läänemaa are typical of this endeavor. What is striking is that a photograph of Laikmaa with his family at his atelier in Haapsalu clearly depicts Girl from Läänemaa on an easel next to another painting in progress: Abyssinian.

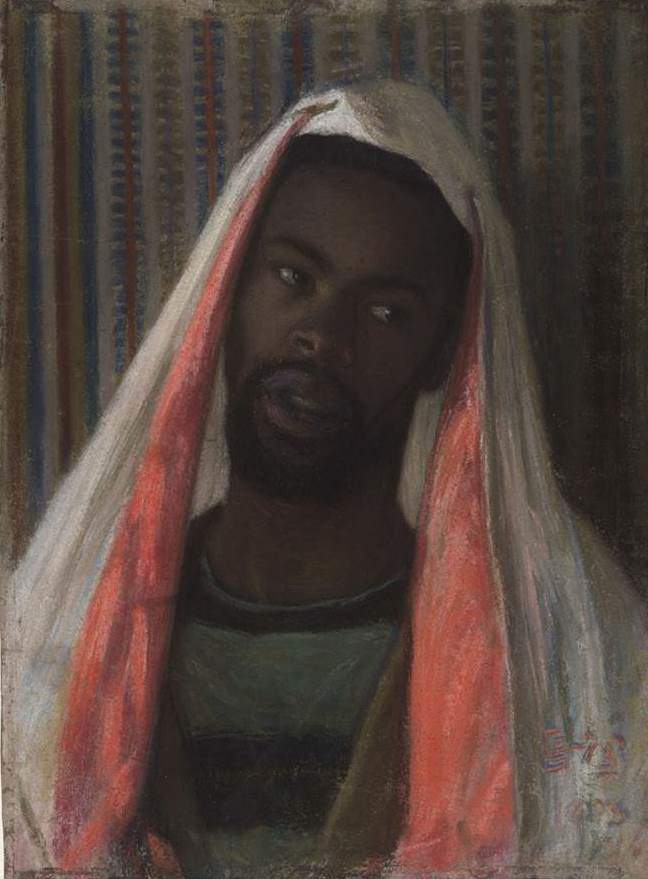

Laikmaa painted Abyssinian in 1903, the same year he painted Girl from Läänemaa. Laikmaa stayed in Estonia throughout all of 1903, so he became acquainted with the model for Abyssinian in Estonia, not abroad.

The African model in a diverse environment

Laikmaa himself was a convivial fellow, and his studio in Tallinn was often home to Estonians and Germans, intellectuals and simple men, noblemen and gypsies, the literati and the bourgeois, royalists and revolutionaries. In such a diverse environment, the African model for Laikmaa’s painting would have certainly been welcome. While one biographer wrote in 1961 that the figure in Abyssinian was “an African who somehow found his way to Tallinn”, art historians revealed as early as 1932 that this man’s name was Samuel Peters.

But why do we care about this portrait of Samuel Peters? The answer is in the title. The word Abyssinian was an ethnonym for Abyssinia, an older name for the Ethiopian Empire.

But why do we care about this portrait of Samuel Peters? The answer is in the title. The word Abyssinian was an ethnonym for Abyssinia, an older name for the Ethiopian Empire.

The Russian Empire began trade with Ethiopia already in the 1880s, and by the 1890s, Ethiopian delegations were sent to the Russian Empire. As an important port city close to St Petersburg, Tallinn could have been an important stop for those Ethiopian delegations, perhaps explaining how Peters arrived to Tallinn.

Ethiopia was also important in the early twentieth century for another reason: it was one of the few African countries to avoid European colonialism. The victory of Menelek II, Emperor of Ethiopia, over Italian forces in 1896 became a testament to African strength and vitality. As a minority within the Russian Empire, Estonians were especially critical of the tyrannous European regimes in Africa. That Ethiopians represented indigenous victory in an imperial age was perhaps admirable for Estonians like Laikmaa, who sought cultural autonomy for his own people.

An expression of admiration and common humanity

The question remains: why is the portrait of Samuel Peters next to Laikmaa’s Girl from Läänemaa? We can note some similarities if we compare the two paintings. Both figures are cropped within the canvas, both figures wear either a scarf or a pink and white head garment. Importantly, the photograph reveals that Laikmaa was still in the process of completing Abyssinian, and the similarities between this portrait and Girl from Läänemaa suggest the artist sought to articulate a commonality.

By 1903 Estonians had been liberated from serfdom for over half a century, but the dark spectre of the so-called “700-year-long night of slavery” loomed large over Estonians in the early twentieth century.

By 1903 Estonians had been liberated from serfdom for over half a century, but the dark spectre of the so-called “700-year-long night of slavery” loomed large over Estonians in the early twentieth century.

Since both Ethiopians and Estonians were recently liberated from foreign oppressors, resulting in independence for the former and increasing cultural autonomy for the latter, the similarities between Laikmaa’s Abyssinian and Girl from Läänemaa suggest not hierarchical difference, but rather an expression of admiration and common humanity.

Laikmaa’s portrait of Samuel Peters is not merely an instance of an “exotic” figure in Estonia. It is a visual testament to tolerance and acceptance in the country.

About ten years later, Laikmaa created a series of portraits of North Africans, which he brought back to Tallinn in 1913. Paintings such as Black Boy are routinely considered to be some of the best works of Laikmaa’s career. These images of Ethiopians and North Africans do not tarnish Laikmaa’s reputation as an important figure in Estonian national culture. The care with which he rendered portraits of Africans is just as delicate and nuanced as that with which he painted his fellow compatriots. Today they peacefully coexist in museum collections across Estonia, revealing the beauty of diversity.

I

Cover: Ants Laikmaa at his Haapsalu studio with sisters Anni and Mai. Please consider making a donation for the continuous improvement of our publication.