While the first Estonian to be declared a saint was a Buddhist, this religion also served as a form of resistance for certain Estonian intellectuals during the Soviet occupation.

Although quite remarkable, the history of Buddhism in Estonia –and in the Western world more broadly – represents only a small chapter in the religion’s long story. Its origins date back to the 6th or 5th century BC in India, where Prince Siddhartha Gautama meditated beneath a Bodhi tree and came to the realisation that the meaning of life lies in the alleviation of human suffering.

Western scientists began to take a deeper interest in Buddhism only in the 19th century. The 1960s and 1970s saw a rebirth – or perhaps a reincarnation – of the religion in the West, fuelled by beatniks and hippies. For them, Buddhism offered a means of expressing opposition to the establishment and seeking connection with the eternal and the intangible.

What follows is a brief overview of the history of Buddhism in Estonia.

Brother Vahindra

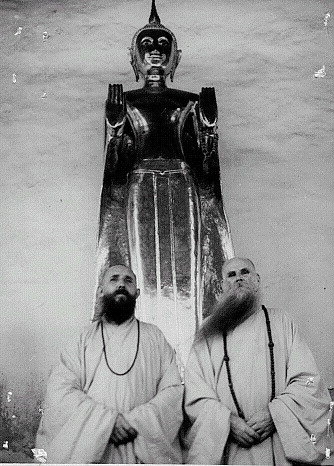

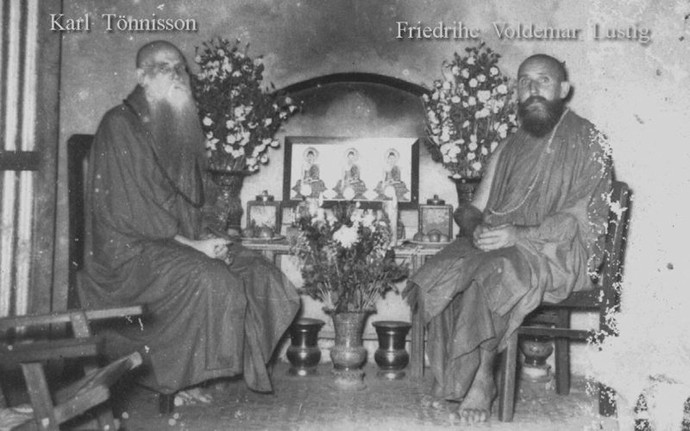

Buddhism was introduced to Estonia at the beginning of the 20th century by a man named Karl Tõnisson (1882–1962), also known as “Barefoot Tõnisson” or Brother Vahindra. His life and actions have secured him a place in the history of Buddhism not only in Estonia but also globally, as he was among the very first Westerners to embrace the Buddhist faith as a monk.

Born in the small Estonian town of Põltsamaa, Tõnisson embraced the Buddhist faith around the turn of the century. He was a colourful and eccentric figure who was not taken seriously at the time – often seen in marketplaces predicting a bleak future for the country and its people, he was widely regarded as a fool.

At some point, Brother Vahindra left Estonia for neighbouring Latvia, where he became a citizen under the name “Karlis Tennisons”. He established a Buddhist temple in the Latvian capital, Riga, and was appointed the first Buddhist Archbishop of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania by the Thirteenth Dalai Lama.

In the early 1930s, Brother Vahindra travelled to Asia with his only devoted disciple, Friedrich Lustig (1912–1989), and never returned to his homeland. He became the first Estonian to visit Lhasa, the capital of Tibet – an exceptional feat at the time, as only devout Buddhists were permitted entry into the city.

Brother Vahindra eventually settled in Yangon (then known as Rangoon), Myanmar (then Burma), where he was held in high regard. Following his death in a temple in 1962, he was declared a bodhisattva – a spiritually advanced being in Buddhism, akin to a saint in Christianity.

Thus, the first Estonian to be declared a saint was, in fact, a Buddhist.

Namedropping up to the present day

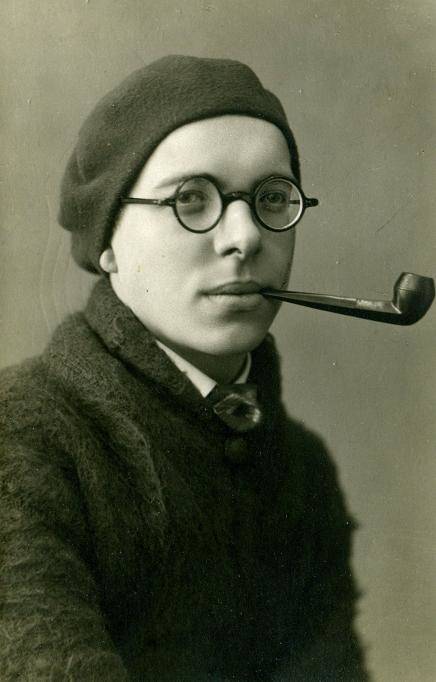

Brother Vahindra was certainly the most colourful of Estonia’s early Buddhists. Perhaps it was partly thanks to him that Uku Masing (1909–1985), the renowned Estonian philosopher, took up the torch and began his own exploration of Buddhism – an endeavour that culminated in a series of lectures and a book titled Budismist (About Buddhism).

Masing, though not as mythical as Brother Vahindra, was nonetheless a worthy counterpart – what he lacked in flamboyance and spectacle, he more than made up for with encyclopaedic knowledge and intellectual depth.

He was also a founding member of the Estonian Oriental Society in 1935. Although the society was forced to close following the Soviet invasion of Estonia in 1940, it was fortunately re-established in 1988. In the meantime, another member of the society – the polyglot and orientalist Pent Nurmekund (1906–1996) – succeeded in founding the Chair of Oriental Studies at the University of Tartu in 1955.

The academic chair went on to nurture another leading figure in the Estonian Buddhist scene – Linnart Mäll (1939–2010), who began his studies there in the 1960s. Mäll, a student of Masing, went on to become a teacher to many future Estonian buddhologists. He was instrumental in translating many of Buddhism’s foundational texts into Estonian.

Thanks to Mäll, it is relatively easy to embrace Buddhism in Estonia – the core texts underpinning its theology (if such a term may be applied to Buddhism) are available in the native language, accompanied by insightful commentary. His work culminated in the publication of three volumes of Budismi pühad raamatud (The Sacred Books of Buddhism) between 2004 and 2008.

Thus, the now well-established Buddhist community in Estonia stands on the shoulders of remarkable predecessors – individuals who were not only pioneers of the faith but also distinguished figures in Estonian academia and society.

Resistance to the Soviet regime

Buddhism in Soviet Estonia could also be seen as a “way of resistance”. The Soviet era brought a halt to most religious practices and education across the country. While Christian denominations continued to operate on a much smaller scale, membership in other religious communities declined significantly.

On the one hand, this climate created a fertile seedbed for the emergence of religious and intellectual luminaries, drawing eager followers to gather around them. The continuity of earlier traditions depended entirely on the “right” individuals in the “right” places –people who possessed both the courage and the capacity to immerse themselves in unfamiliar cultural and religious concepts. Curiously, this remains true even in the free world today.

The convergence of intellectual curiosity and religious devotion was a vital precondition for the emergence of a viable religious movement. A certain degree of political finesse was also necessary. For instance, when Linnart Mäll was barred from working at the University of Tartu as a researcher, he was instead appointed “engineer at the Chair of Oriental Studies”. “In the eyes of the state organs, Buddhism and dissidence were synonymous,” Mäll later remarked.

Buddhist resistance to the Soviet occupation of Estonia was, naturally, a peaceful one – true to the core principles of the faith. Instead of battle-axes and rage, it relied on sacred texts and contemplation. Paradoxically, this strong emphasis on academic study led to a certain tension between scholars – the theoreticians – and practitioners – the believers. The latter were often referred to by the former as “village mystics” (a term arguably kinder than “village idiots”, at least).

Estonian Buddhist Brotherhood

There was also a group known as the Estonian Buddhist Brotherhood – nicknamed Taola – which was founded under the guidance of Vello Väärtnõu in 1982 in Tallinn.

The brotherhood operated as a self-funded organisation, with its members working as boilermen – a profession commonly adopted by the resistant intelligentsia during Soviet times. Each member specialised in a different field of Buddhist studies, with the aim of spreading the religion’s philosophy and way of thinking among Estonians.

Members of Taola also maintained close ties with the Ivolga Monastery in Buryatia, a republic in Siberia. They visited the monastery on several occasions, engaging in discussions with elderly lamas, who, in turn, made visits to Estonia.

Taola members also built the first stupa in Estonia – at the summerhouse of artist Jüri Arrak in Pangarehe. Three more stupas followed, constructed between 1984 and 1985 in the village of Tuuru in western Estonia.

Taola was under constant surveillance by the KGB, the Soviet Union’s internal security service. The group’s Buddhist library was “cleaned out” on several occasions, with large quantities of Tibetan texts, thangkas, slides, and reels of Tibetan manuscripts confiscated from Vello Väärtnõu.

In 1988 – three years before Estonia regained its independence –Vello Väärtnõu was deported from the country (he would return years later), effectively bringing an end to the successful activities of the Estonian Buddhist Brotherhood.

Buddhism in Estonia today

Our ignorance of religious matters has paved the way for numerous conspiracy theories and esoteric interpretations – most of which tend to lack both depth and coherence. It is all too easy to construct a spiritual system for an audience that has neither the means to question it nor the necessary background to assess it critically.

Make no mistake: Buddhism is no easy escape for pretenders. It is a religion. Despite its seemingly relaxed structure (the key word being seemingly – a reflection of our flawed religious education) and its gentle public image, it is built upon a clear hierarchy, specific principles, and defined obligations. Above all, it demands decision and devotion: choose your path – and remain committed to it.

According to the 2011 census, 1,145 people in Estonia identified themselves as Buddhists. However, this figure reflects those who consider themselves Buddhist, rather than the actual number of members in organised Buddhist communities or congregations –which is estimated to be roughly five times smaller.

However, the number of people who attend Buddhist meditation evenings is certainly several times higher than 1,145. This likely reflects a broader tendency among Estonians to avoid defining themselves too readily or rigidly. Added to this is the more universal phenomenon of “convenience believers” – individuals who engage with spiritual practices without formally committing to a particular faith.

What do we actually know about Buddhism?

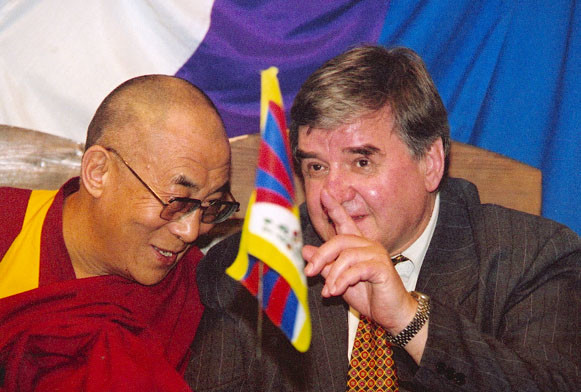

Here are some of the keywords offered by young students in Tartu: the Dalai Lama, stress management, non-violence, vegetarianism, contemplation, enlightenment, Eckhart Tolle, karma, previous lives, India, tolerance, well-being, Buddha, Woodstock, meditation. Others remarked that it’s simply “a bunch of concepts belonging to some other Far Eastern religions.”

This writer has always remembered Buddhism by the numbers 3, 4, and 8. The three precious jewels of Buddhism are Buddha (the teacher, the Awakened One), dharma (the teaching), and sangha (the community).

Then come the four noble truths: there is suffering in this world; there are causes of human suffering – such as the human body, the craving for pleasure, and illusions; to be free of suffering, one must let go of desires and yearnings; and to reach a state beyond suffering, one must follow the eightfold path. This path centres on becoming a wise, ethical human being. Makes sense, doesn’t it?

Logic and rationality may seem like surprising qualities for a “spiritual” movement, yet I believe these are precisely what drew Estonians to Buddhism during the Soviet era – and what continues to attract them today.

While talking about the Resistance to the regime, you should mention

that a Buddhist Vello Vaartnou and other Estonian Brotherhood Buddhists

were the ones who firstly proposed the idea of independent Estonia and

the Estonian National Independence Party in January 1988. (See New York

Times, 1988)

You also skipped the foundation of practical Buddhist

tradition in Estonia by Vello Vaartnou, who established the first

Estonian Buddhist Brotherhood already in 1982, when Mall said that he is

not a Buddhist and is dealing with science only. ( I heard it

personally) However, you use often photos about the stupas built

Vaartnou, would be logical to ask permission and mention and credit the author. I recommend

to look for information about Estonian Buddhism from estoniannyingma encyclopedia.co m

as well from Vaartnou`s last project, http://www.chinabuddhismencyclopedia.com

(launched at UC Berkeley) it helps to be more exact and scientific in

your works.

Hi Mary,

Thank you for your comments. Just want to clarify that we did credit the authors of the photos. Besides, we specifically provided a link to http://www.estoniannyingmaencyclopedia.com (at the bottom of the article). Best, Editor-in-chief/Estonian World.

Hi Silver, I see that you did not get my point. It is not about credits but about the section ‘Resistance to the resistance regime’.

You

do not say a word that in January 1988, Estonian Buddhist Vello

Vaartnou announced the formation of an actual opposition party, Estonian

National Independence Party, aimed at re-establishing independence of

the Estonian Republic. It

was sensational event in the world at that time because first time in the 70

years history of Soviet Union the leaders in Moscow were faced with the

proposal of the creation of an opposition party. I wonder what was your intention to hide this fact…