Chili peppers are not part of Estonian cuisine. But they have helped make some of Estonia’s most distinguished sons and daughters famous at the Economist magazine.

I should begin by explaining that my enthusiasm for all things Estonian is not my only eccentricity. Among the others are obsessive interests in railways, cricket – and spicy food. My sister and I frequent a London restaurant called “Hot Stuff” and at Christmas and birthdays exchange bottles of hot sauce with names like “Wild Dog” and “Liquid Fire”.

Chili peppers named after famous Estonians

Although we don’t believe in serious sibling rivalry, a bit of competition is fun. So when she started to grow chillies in her garden, I decided to grow bigger and better ones in my office. Soon I had a tray (a colleague’s unused inbox) filled with compost and a two dozen tiny green sprouts. “What are you going to call them?” a colleague asked

As a joke, I answered “they’re all famous Estonians”. Then I thought to myself, “why not?” I started jotting down names at random of Estonians I admire and would like to have as company in my office.

Otto Tief. Jaan Tõnisson. Jüri Kukk, on whose behalf my mother, an Amnesty International stalwart, used to write letters. Other heroes of the resistance such as August Sabbe and Alfons Rebane. Aili Jürgenson and Ageeda Paavel, the teenage girls who blew up the first Soviet war memorial in Tallinn and were sent to Siberia. Kristjan Palusalu, the great prewar wrestler (who some say was cheekily chosen as the model for the real Bronze Soldier).

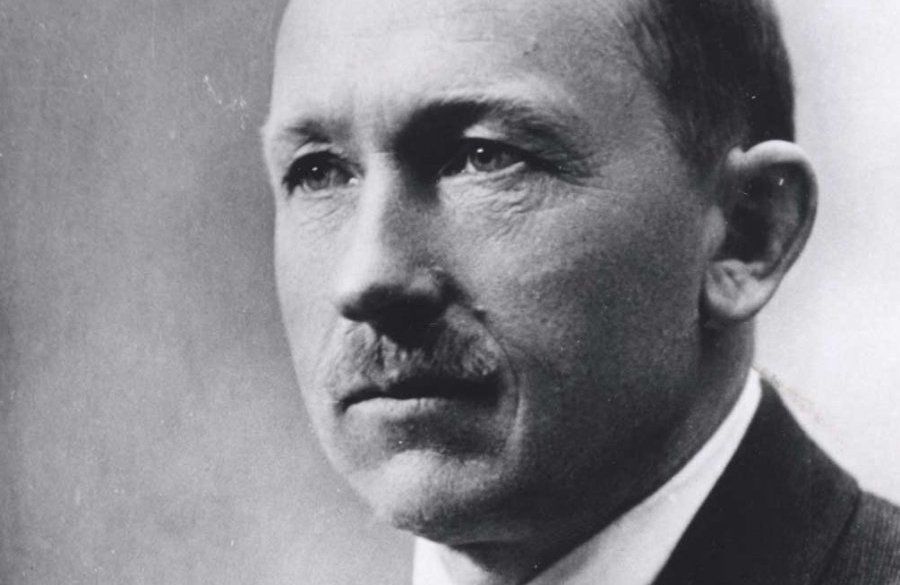

Then my favourite writers: Lydia Koidula, Betti Alver. Jaan Kross and Jaan Kaplinski. I researched the Estonians who had been on postage stamps and who had public memorials. I added Friedrich Kreutzwald, Carl Robert Jakobson, Jakob Hurt and some more pre-war politicians.

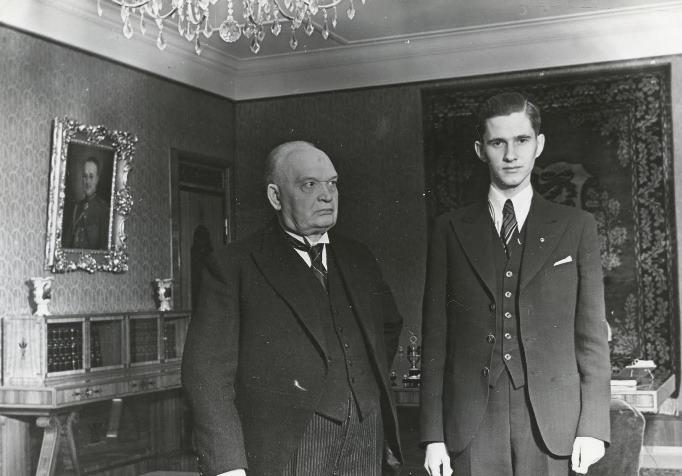

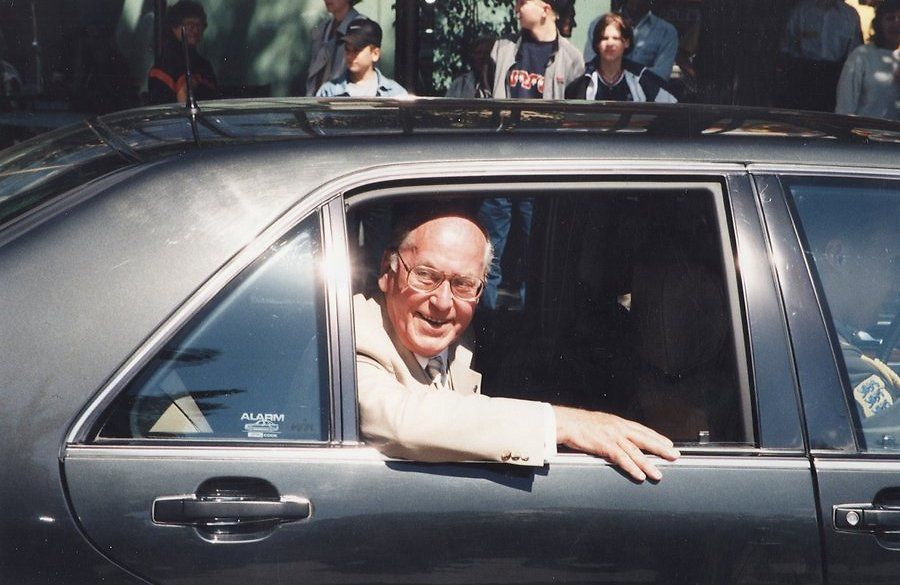

All the heads of state of the prewar republic deserved mention, I reckoned. I added the two most impressive Estonians I met: Ernst Jaakson and Lennart Meri. All that was missing was an English connection (Rebane doesn’t count). I settled on Gert Helbemäe. I doubt many modern Estonians have heard of him, but he was a leading light in Estonian literary exile circles in Britain until his death in 1970.

I bought more trays, pots and labels and started potting out the seedlings. Working out how to arrange them on the windowsill proved surprisingly time-consuming. At first I tried to do it logically: all political prisoners over there, pre-war politicians here, 19th century writers in one corner, 20th-century ones in the other, and so on. But my sense of mischief soon triumphed. Why not Koidula in bed with Kreutzwald? Their real-life epistolary relationship was tragically abortive (I’ve just been reading Madli Puhvel’s excellent book about it).

But it seemed a shame not to transcend the boundaries of time and space more radically. I decided that it would be more fun for Koidula to meet Betti Alver, and for Kreutzwald to get to know the latter-day literary giants such as Kross and Kaplinski.

It was the same with the politicians. Initially I just laid them out according to a real-life chronology. But it seemed much more interesting to put Ernst Jaakson and Konstantin Päts together. I created a “military heroes” tray where Sabbe, Laidoner and Rebane could exchange stories.

I couldn’t decide what to do with Lennart: he would fit in well everywhere and would be sorry to miss out on meeting others. In the end I decided he should share with Tammsaare and Jakobson: he would be the right person to explain to them what had happened in the years since their death. I spent a lot of time trying to work out whether people had met in real life: did Rebane and Laidoner know each other, for example? What were Ernst Jaakson’s relations with Rebane like?

In the process, I got hopelessly muddled about which chili was which. Some are “Scotch Bonnets”, some are “Habaneros” and a few from the world’s hottest chili, the “Dorset Naga” (this is so spicy that it is the only food product that cannot be bought by under-16s in a British supermarket).

Chili peppers creating interest about Estonia

Then something rather odd happened. My colleagues are very patient with my enthusiasm for Estonia’s achievements. We do write about Estonia when it matters (on everything from the euro to the high anti-corruption scores, the flat tax, e-government and so on). We are robustly supportive of Estonia’s position on language and citizenship laws. I even managed, a few years ago, to get three pages on Finno-Ugric grammar into the Christmas edition. We wrote a big obituary for Lennart Meri. But they maintain a polite distance to the subject. If I start talking about Estonia at office parties, I usually find that my audience is two pot plants and an intern.

My own plants changed that. My office is next to the kitchen, so I have a lot of people stopping by, as well as the cartographers, layout artists, fact checkers and other journalists who visit to discuss the paper’s international section (editing that is now my main job: eastern Europe is a sideline). Lots of them, ranging from interns to even my bosses, started asking me about the names on the labels. I was only too pleased to explain.

The answers proved rather shocking. It is one thing to know dimly about the miseries of communism in a faraway country. It is another to be given a real life example. “Did all the Estonians get sent to the Gulag?” asked one colleague, after I had given a quick explanation of the fates of Päts, Laidoner and Meri.

As more colleagues started asking questions, I prepared some short biographies and photos, trying to find other hooks for their interest. A colleague specialising in Iraq was particularly interested to hear how Laidoner, on behalf of the League of Nations, had drawn Turkey’s eastern boundary after the First World War.

The plants named after people who had been in Siberia had to be closest to the window in order to enjoy the sunlight. As Jüri Kukk had died from forcefeeding, I was particularly careful not to over-water him.

Oddly, the plants did not grow to match their names. Tammsaare, fittingly for a giant in literature, proved a giant in his botanic reincarnation too. Given his physical prowess, Kristjan Palusalu should have been similarly huge, but he remained a spindly little thing. Jüri Kukk, by contrast proved to be a great sturdy plant, as did Marie Under. Ants Piip and Jakob Hurt simply refused to grow more than a couple of centimetres.

Some of my visitors began to think it would be nice to have their own Estonian. After a lot of repotting into larger containers, my windowsill was getting rather crowded. I know Estonians hate crowds, so in principle I wanted to give them more space. But it was hard to give them away. Initially I said that those nobody who had been in exile in real life should be moved out of my office. Losing ones’s homeland once is enough for anyone.

Female poets were in particular demand. The deputy editor, Emma Duncan, took Betti Alver. But I simply refused to get rid of Lydia Koidula. It is bad enough having her disappearing from the 100 kroon banknote, let alone having her leave my office. One colleague insisted on a female poet, but I persuaded him to take Tammsaare.

“Chekist” insects

In the summer, I was away for several weeks, but our editorial secretary, in between her other tasks (arranging trips to Iraq and Afghanistan, getting the Chinese embassy to give visas, and helping journalists recover notebooks left in trains and planes) paid scrupulous attention to the watering instructions I left behind. All the plants were alive and well when I got back.

But my colleagues were not happy. One senior journalist said grimly “It’s like the Niger Delta here”. I could see why. A plague of small black insects was buzzing round my plants, and escaping to other offices. I apologised profusely, explaining that these were “chekist” insects who were trying, as so often in the past, so sabotage Estonia. But the joke fell flat. On close examination, I think the compost, not the plants, was to blame. There was no time to lose. Muttering “nyet rastenia, nyet problemy” I took ruthless action, putting a dozen of the smaller plants into the bin and repotting the survivors in new compost.

My colleagues are happy again. But now they are impatient for the plants to flower and fruit. That requires some sunny weather. The Economist can influence a lot of things. But not that.

This article was also published in Estonian by Estonian newspaper Postimees.

After 10 years in Estonia I can so appreciate your ironic metaphor. You’ve chosen a great way to spread Eesti’s real flavor, its history and sacrifice, if not necessarily its cuisine.

What a great hobby, Edward! Hope to see you in Latvia again sometime soon, and be sure to bring some of the peppers with you. I’m also a fan of spicy foods and have Nexium bills to prove it. 🙂