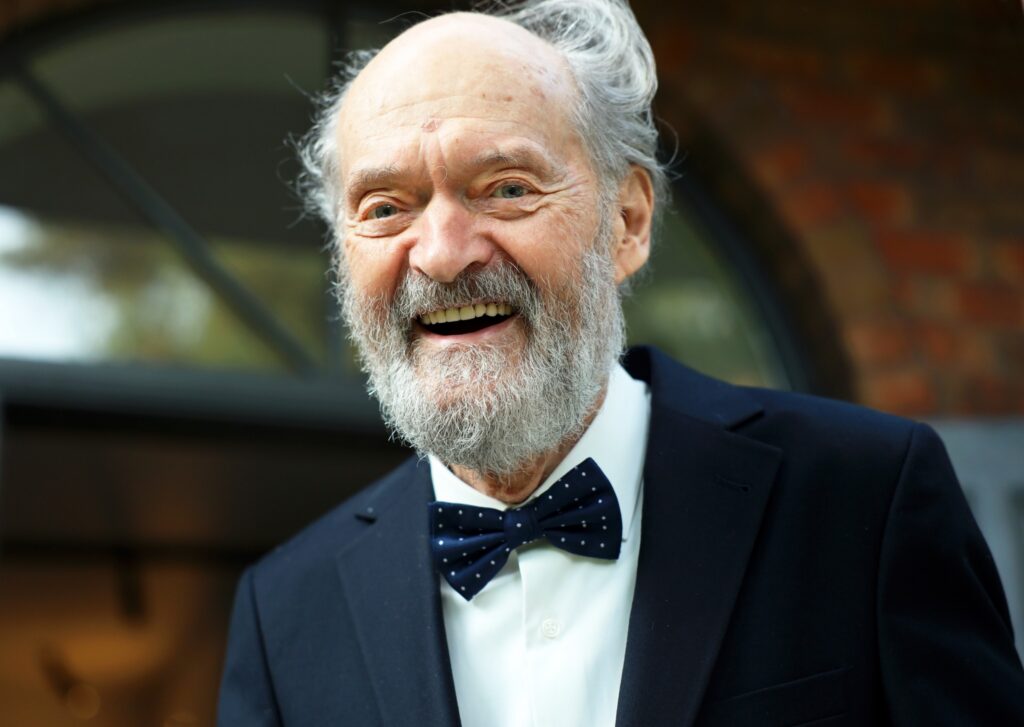

Arvo Pärt, Estonia’s most celebrated composer and one of the most widely performed living musicians in the world, turns 90 on 11 September; his work, often described as austere and luminous, has for half a century stood apart from the noise of contemporary culture.

When Arvo Pärt turned nine, he would bike to the central square of Rakvere, a town in northern Estonia, circle a lamppost, and listen to live radio concerts spilling from a loudspeaker fixed high above the street. The boy could not have known that this hunger – for sound, for something larger than his small Estonian town – would one day bring him to Carnegie Hall, to the Vatican, to Stockholm’s royal palace. Yet even then, in a country about to be submerged by Soviet rule, Pärt was listening with a devotion that bordered on prayer.

Ninety years later, the boy has become the world’s most performed living composer, his name spoken in the same breath as Bach and Beethoven. Estonia hails him as its most luminous cultural export. But Pärt himself still frames his achievement in disarming simplicity: “All is one,” he has said, reducing a lifetime of searching to a phrase as stark as a single note.

The crooked road of a Soviet youth

Born in the Estonian town of Paide in 1935, raised by his mother in Rakvere after his parents’ separation, Pärt’s early years unfolded against the backdrop of two occupations: Nazi and then Soviet. Relatives were deported to Siberia.

The scars of that rupture shaped his revulsion to power imposed from outside. Yet amid the fear, music crept in – first piano lessons, then oboe and percussion during his Soviet military service, then composition at the Tallinn Conservatory under Heino Eller.

Even in his twenties, Pärt was never docile. His Nekrolog (1960) marked the first use of serialism by an Estonian composer and drew Moscow’s attention. Credo (1968), a bold fusion of Bach with twelve-tone defiance and an open Christian declaration, provoked scandal and was swiftly banned. The young composer became both celebrated and suspect, pulled between official praise and censorship. “My crooked road of searching for beauty, purity and truth – of seeking God – began in the 1960s,” he later reflected.

Silence before renewal

By the late 1960s, disillusioned with modernist techniques and the clash of styles, Pärt fell silent. For nearly eight years he produced almost nothing, withdrawing into the study of Gregorian chant, Renaissance polyphony, and Orthodox liturgy. He read scripture, lived modestly with his wife Nora on the outskirts of Tallinn, and wrestled with despair. At times, she later admitted, it seemed he might give up composing altogether.

Then came the breakthrough. On a February morning in 1976, Pärt set down a piano piece so stripped of excess it seemed hardly music at all. Für Alina contained within it the germ of an entire new language: tintinnabuli, the “little bells.” Two voices – one moving stepwise, the other tracing a triad – created a sound world at once severe and consoling. It was the beginning of a second life. Within months came Fratres, Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten, and Tabula Rasa.

Arvo Pärt playing Für Alina.

Tintinnabuli defies neat definition. Some call it minimalist, others mystical. Listeners often describe the sensation less than the structure: a clearing of mental space, a feeling of being held. To conductor Tõnu Kaljuste, who has devoted decades to Pärt’s work, the music “is both ancient and new, as if time itself has collapsed into a single note.”

Its reach has been startling. In the 1980s, when Pärt emigrated to Vienna and then West Berlin, his music seemed too inward for either Soviet collectivism or Western modernism.

But then Manfred Eicher of ECM Records heard Tabula Rasa on his car radio and pulled over. Their collaboration produced a string of recordings that carried Pärt’s name into hospitals, monasteries, and concert halls across the globe. In New York, young men with AIDS clung to Tabula Rasa as a soundtrack to their final days. In Rome, Passio resounded in sacred spaces. In Hollywood, fragments of Pärt’s music slipped into soundtracks as shorthand for the eternal.

Arvo Pärt’s Tabula Rasa.

In recent decades, the honours have come in abundance: Japan’s Praemium Imperiale, Sweden’s Polar Music Prize, the Ratzinger Prize from Pope Francis, and the Royal Philharmonic Society Gold Medal. Just this May, Monaco made him Commander of its Order of Cultural Merit. For Estonians, every award affirms not just Pärt’s stature but the visibility of a nation that fought for its voice.

A composer in a time of crisis

Yet Pärt himself has always kept awards at arm’s length. He rarely explains his work. He prefers paradoxes: “One and one makes one.” He compares his music to white light, broken into colours only when refracted through the prism of listeners. What matters is not the composer, he insists, but the communion of sound and silence.

Pärt’s music has always seemed prophetic, but in 2020, during the coronavirus pandemic, he put the insight into words. In a rare interview with Spain’s ABC newspaper, he called the pandemic “a total fasting for the whole world,” forcing humanity to focus on what is essential.

“This tiny coronavirus has showed us in a painful way that humanity is a single organism and human existence is possible only in relation to other living beings,” he said. Relationship, he insisted, should be understood as “the ability to love.” The pandemic, he suggested, had sent us “back to first grade” – a reminder that before demanding justice from the world, we must first tend to those closest to us.

For a composer who had already built a lifetime on paring sound down to its essence, the lesson felt continuous with his music: adversity clears away excess, leaving only what is vital.

A birthday in miniature

At ninety, the tributes range from monumental to intimate. ECM has re-issued Tractus on vinyl, summoning his long collaboration with Manfred Eicher. Vox Clamantis has premiered a long-dormant work, Prayer to the Holy Trinity. The Arvo Pärt Centre has published a book-album of private musical greetings written over half a Century – playful, witty pieces that show a composer still capable of mischief.

And across Europe, choirs and orchestras are marking the milestone. The Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir, under Tõnu Kaljuste, has toured Paris, Prague, Dresden and Munich with programmes built around his choral music. On 31 July, they carried that torch to London’s Royal Albert Hall, dedicating a Late Night BBC Prom to the “father of Holy Minimalism.” The concert, broadcast live, placed Pärt’s serene Da pacem Domine alongside works by Bach, Rachmaninoff, Galina Grigorjeva and Veljo Tormis – Pärt’s first teacher.

“The overarching theme of the concert could be described as peace,” Kaljuste said. “From inner serenity to the yearning to end war.” The juxtaposition was stark: Tormis’s ferocious Curse Upon Iron against Pärt’s meditative plea for peace. In that contrast, Pärt’s stillness became its own kind of protest, a reminder that silence can resist as powerfully as sound.

Arvo Pärt – Da pacem (Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir / Paul Hillier, 2006).

Why it matters now

What explains the persistence of his appeal? Bachtrack’s 2024 statistics place him just behind John Williams as the most performed living composer. Fratres and Spiegel im Spiegel are heard in as many countries as pop hits. To some critics, the music is too gentle, too willing to please. But to audiences across faiths and languages, it offers not escape, but a pause – an invitation to listen inward.

In an age defined by fracture, Pärt’s music insists on unity – not as abstraction but as lived experience. Each tintinnabuli line folds into another until one and one do, impossibly, become one. The boy circling a loudspeaker in Rakvere could not have imagined such reach. Yet perhaps he sensed already that music was the surest way of saying: we are all in this together.

At ninety, Arvo Pärt has not ceased to remind us. The sound he shaped in his search for purity continues to resonate, carrying its quiet promise of unity to listeners everywhere.

Read also: Arvo Pärt: a visual retrospective and Pictures: Arvo Pärt at 90