Chris Glew, the London editor of Estonian World, writes from what used to be an ever-bustling city that, due to the coronavirus crisis, is deserted, with theatres closed, and the only people you (mostly) meet on the streets are the homeless.

In any other circumstances, it would have been annoying. As a rule, I can’t tolerate busking – it not only invades the senses with no option but submission, but it drowns out public service announcements, especially in stations.

But in Trafalgar Square on Saturday, outside the (closed) National Gallery, there was an almost haunting sadness – the slow, painful notes of a lone busker with his guitar, playing “The House of the Rising Sun” to an audience of me, my wife and some pigeons. The sun had risen, but London stayed home. Even Lord Nelson couldn’t bear to look (although as he’s been facing Portsmouth ever since his eponymous column was erected; it can’t be personal).

Striking up a conversation between tunes, I finally ask, “why aren’t you at home?” “Why aren’t you?” comes back the busker’s obvious reply, and I didn’t know what to say. My platitudinous and almost cliched response about it being “a nice day to see London” sounded as bogus and ridiculous as it was. Of course, he needs the money – or whatever money he can scrape together performing to a city in effective lockdown.

“They talk to me like a person”

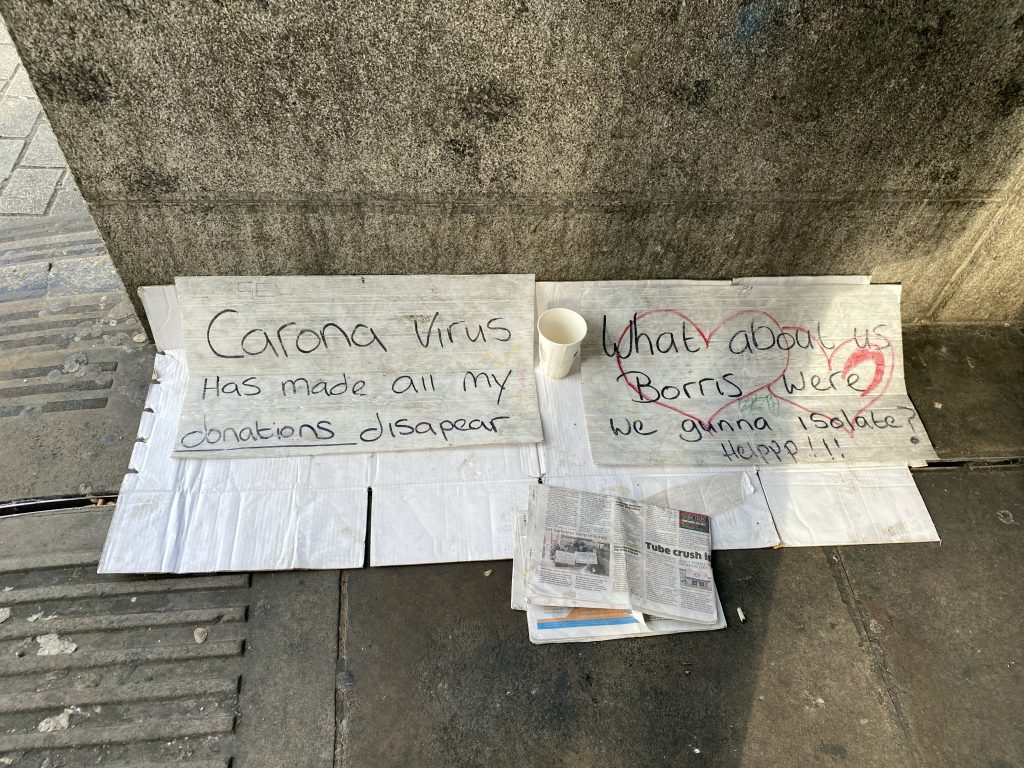

I spoke to a homeless man sleeping opposite the Houses of Parliament, in a small covered area near Westminster underground station. He sleeps next to two placards that read, “carona virus has made all my donations disapear” and “what about us Boris, were we gunna isolate? Helppp!!!” You can only fault his grammar. His parting words were, “it’s quite nice to speak to people and they talk to me like a person”.

A number of homeless people told me that while there is a dramatic reduction in footfall, and total “takings” (for want of a better word) are down, those individuals who do donate are donating more. “It used to be loose change and a couple of quid, but I’ve picked up a few fivers and one tenner,” a lone man told me. A night in a shelter costs about £15.

Ironically, you would expect the homeless population of London to resent the – what must seem trivial – panic of those who have a “home”. Strangely, they don’t.

“We’re all human,” a lone lady sheltering near Embankment underground station advised. “If I’d been back in my old home, and I used to have a big house back when I was younger, I’d be doing what everyone’s doing now, stocking up and stuff. Can’t blame people, can you?”

Keep calm and carry on

As London is barely occupied, the scale of the homelessness problem has become ever more stark. With empty streets, the only people you encounter are the homeless. In a 15-minute period, I was approached by six people asking me for money. A month ago, I would not have been approached at all. Naturally, there are the abusive drunks, the aggressive beggars and the threatening followers. But they are relatively few and far between.

With their wartime stoicism, as is by virtue of their situation, the norm, the homeless population of London have coped with the COVID-19 crisis better than any other definable group – when you live on the streets, the threats are frequent, immediate and visible. I have never seen “Keep calm and carry on” so visibly demonstrated.

Elsewhere, life continues in a sometimes farcical manner. Restaurants, bars, cafes and other establishments that provide food or beverages have been told to only serve takeaway food. Yet, at Victoria station (the second busiest in the UK), there was a cadre of co-workers, evidently having just left work, enjoying their takeaway food together on the communal seating area – in far more cramped conditions that the seating available in their chosen choice of eatery, had it been available.

Racism has become more obvious

Covent Garden, home to its famous market, numerous shops and the Royal Opera House, usually teeming with people, is deserted. Theatres are closed, with “Curtains temporarily lowered”. The excuses are varied and euphemistic – some establishments have lengthily detailed how they will “heed the Prime Minister’s advice”, some are “diverting their energies”, and some are “temporarily closing for operational reasons”. Only one I saw was succinct – a restaurant in Chinatown stated simply “CLOSED DUE TO VIRUS – COME BACK LATER”.

Trains, both regional or part of the London Underground, are almost empty. Racism, which is never subtle, has now become even more obvious. Bags and coats are shuffled and carriages are changed when Chinese – or more precisely, Chinese looking – people board a train. If you cough to clear your throat, there is a glance. Do it twice, and there is a look of alarm. Three times and there is movement.

The conversation I will remember the most today was when I asked a homeless man how he was coping.

“How do I deal with something I can’t see that could kill me, you mean? I do that every day. It’s called ‘cold’, mate.”

For the latest developments in Estonia, follow our special blog on coronavirus.

The opinions in this article are those of the author. Cover: Covent Garden, home to its famous market, numerous shops and the Royal Opera House, usually teeming with people, is deserted. Photo by Chris Glew.