Imbi Paju, a Helsinki, Finland-based Estonian journalist, writer and filmmaker says in a speech when accepting the Heli and Arnold Susi Mission Award for the Courage to Speak Out that remembering our history is important because history is not history – it is us right now.

Editor’s note:

Arnold Susi (1896 – 1968) was a lawyer and the minister of education in the Estonian government of Otto Tief, established on 18 September 1944 during the Second World War – just before the Soviet troops occupied Estonia again.

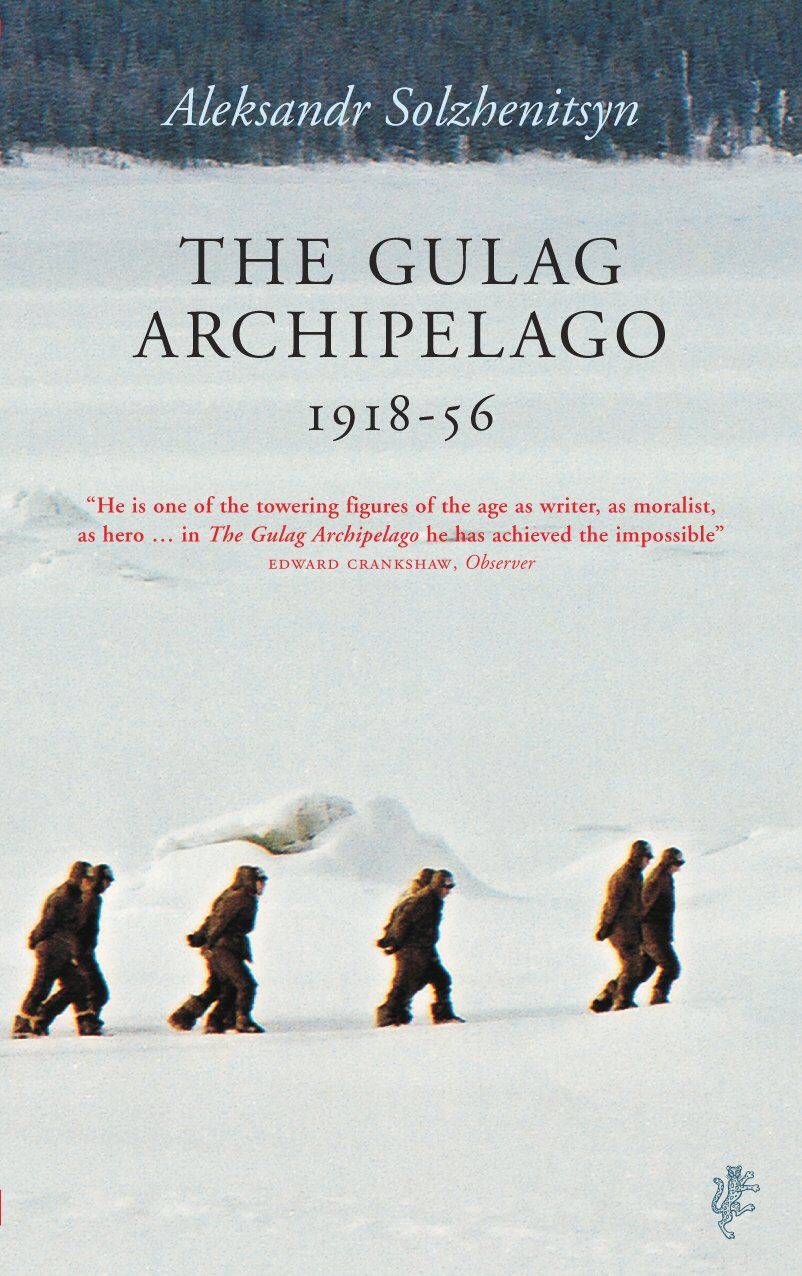

Susi was soon arrested by the Soviet authorities. While held at the KGB Lubyanka Prison in Moscow in 1945, he befriended Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who would later become the writer renowned for The Gulag Archipelago (first published in Russian by a French publishing house in Paris in 1973) – a book that describes the horrors of the Soviet forced-labour camps.

While in prison, Susi got Solzhenitsyn acquainted with the principles of the European justice system and court practice as well as with the democratic principles of the constitution of the Republic of Estonia.

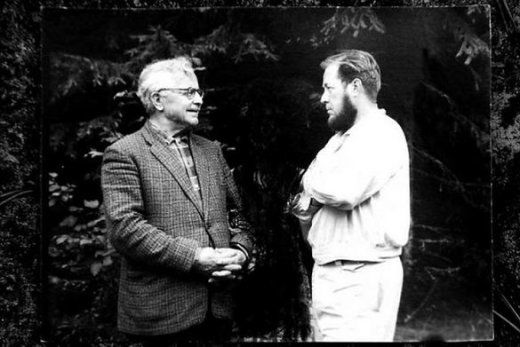

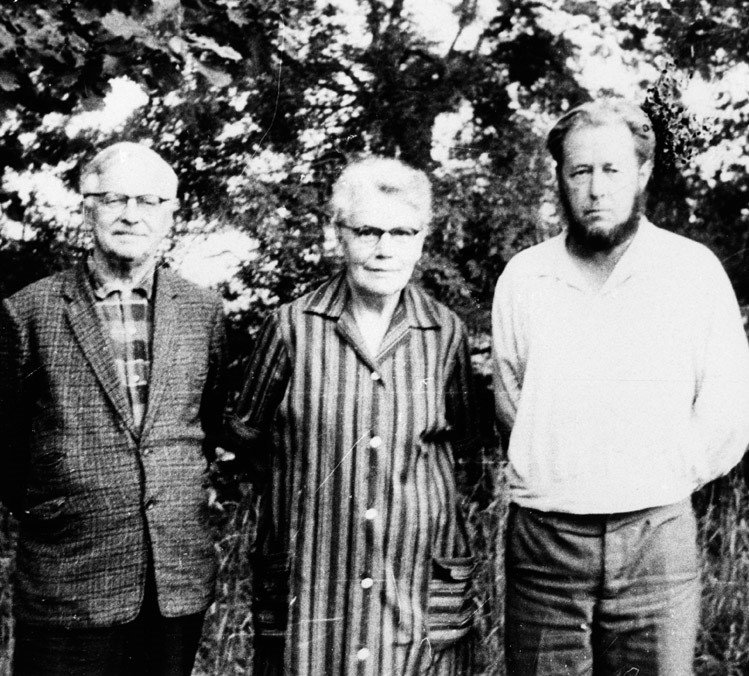

In 1963, the two men met again in Estonia and Solzhenitsyn hid at Susi’s country house to write The Gulag Archipelago. He entrusted Susi with the original typed and proofread manuscript of the finished work, after copies had been made of it both on paper and on microfilm. Arnold Susi’s daughter, Heli Susi, subsequently kept the “master copy” hidden from the KGB in Estonia until the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.

In early 2019, The Heli and Arnold Susi Mission Award for the Courage to Speak Out was initiated by the Estonian ministry of justice. The award recognises the courage to love Estonia, the freedom of Estonia and the truth. It also recognises the dedication to have it as one’s literary mission – and to be successful internationally in this mission.

The first person to receive the award was Imbi Paju, a Helsinki-based Estonian journalist, writer and filmmaker. “Imbi Paju has presented topics regarding the Estonian historical memory with her films and books in almost all European countries as well as in Asia and North America. The subject under the question is always the same – occupation, human rights and vulnerability of human life,” Urmas Reinsalu, the minister of justice, said while presenting the award.

Paju won international attention with Memories Denied (2005), a documentary film and a book by the same name. Both the film and the book deal with her mother’s experiences in a Soviet slave labour camp, the occupation of Estonia by the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, and the attempts by totalitarian regimes to destroy human memory. Memories Denied has been translated and published in Estonian, Finnish, Swedish, English, Russian and German. In 2007, it was selected for use in the Swedish school programme, Living History, which deals with both Nazi and Communist crimes.

Estonian World publishes Imbi Paju’s speech (in a lightly edited and shortened format) she gave at the ceremony for the Heli and Arnold Susi Mission Award for the Courage to Speak Out on 4 January 2019.

***

Firstly, I am grateful for the exceptional honour of being the first to receive the Heli and Arnold Susi Mission Award for the Courage to Speak Out. Behind the actions of every person is a story which is, on closer examination, related to our collective sub-consciousness, the life, life-stories, achievements and contradictions of society.

In order to see this all more clearly and to perceive the impact that certain people have on us and our actions, we must keep these stories constantly in our minds, especially now that the world is wavering again.

The examples these people and their stories set, create and reinforce the identity and understanding of oneself – on a country level as well – keeping our heads clear and helping us stay on the democratic path at a time when populism, ideological stigmas, fake news and other noise cause uneasiness, to the point of people talking about a post-truth era. We need a compass right now.

When preparing this speech, I talked to many people who have a deep interest in the actions and stories of Arnold Susi, Sworn Advocate, minister of education during the government of Otto Tief, and Arnold’s daughter Heli.

I will start with examples from our neighbours. Finnish non-fiction author and historian Erkki Vettenniem has just published a book, which has also been translated into Estonian, Solženitsyn. Elämä ja eetos [Solzhenitsyn. Life and Ethos], revealing the part that Arnold Susi, Heli Susi and other Estonians played in the creation of Solzhenitsyn’s book, The Gulag Archipelago. The book revealed the Soviet Union’s crimes against humanity and gave human suffering a face and a voice.

I will start with examples from our neighbours. Finnish non-fiction author and historian Erkki Vettenniem has just published a book, which has also been translated into Estonian, Solženitsyn. Elämä ja eetos [Solzhenitsyn. Life and Ethos], revealing the part that Arnold Susi, Heli Susi and other Estonians played in the creation of Solzhenitsyn’s book, The Gulag Archipelago. The book revealed the Soviet Union’s crimes against humanity and gave human suffering a face and a voice.

Heli Susi, as an involved party, has said that the book remains a bit superficial. The writer admits this but explains that Estonians themselves have not made this story important to the world. One could only hope that some Estonian museum of occupation would make the story permanently visible on the 100th anniversary of the birth of Solzhenitsyn; that it would be visible in the Estonian anniversary year’s cultural project focusing on foreign countries; that this is the time when the state of Estonia reacts and moulds this into a large narrative.

Arnold Susi a key figure of Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago

I mention this fact because the name of Arnold Susi, thanks to whom this masterpiece was created, is referred to as a key figure of Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago in large international periodicals and newspapers such as The Economist, The Guardian, The Independent and others.

The name of Arnold Susi was also internationally mentioned in the eulogies written for the writer, Jaan Kross, in 2007, because this national writer when a young lawyer stood for the independence of Estonia and was a member of the National Committee of the Republic of Estonia (a self-styled resistance movement in German-occupied Estonia, established in March 1944 – editor) where Arnold Susi was one of the key figures.

But even so, Arnold Susi is internationally still too little known. He wrote a thousand pages of memoirs, without really believing they would be published, and yet they were published and his book, Võõrsil vastu tahtmist [Unwillingly Abroad], would definitely raise interest outside Estonia as well.

Last year, which was the 90th year of activity of the Estonian Centre of PEN International, I found in my mailbox a letter from the novelist, poet and translator, Kätlin Kaldmaa, the president and foreign secretary of the Estonian Centre of PEN International; she proposed in this letter that we should choose Heli Susi to be an honorary member of PEN – precisely because she risked her freedom and life when helping Solzhenitsyn when he wrote The Gulag Archipelago.

Last year, which was the 90th year of activity of the Estonian Centre of PEN International, I found in my mailbox a letter from the novelist, poet and translator, Kätlin Kaldmaa, the president and foreign secretary of the Estonian Centre of PEN International; she proposed in this letter that we should choose Heli Susi to be an honorary member of PEN – precisely because she risked her freedom and life when helping Solzhenitsyn when he wrote The Gulag Archipelago.

The idea seemed wonderful, and being inspired by the PEN decision, I organised a small discussion on the topic during the Võtikvere Book Village literary festival in August of last year. Unfortunately, Heli Susi was unable to participate in that small forum, but the topic was introduced by Ivar Tröner, a cultural historian who studies Russian literature. He was joined by journalist and thinker Jüri Estam, a close acquaintance of Heli Susi.

Ivar Tröner reminded us that no other world writer nor Nobel laureate has written about Estonians as respectfully and warmly as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Jüri Estam recalled that when Arnold Susi was imprisoned in the Lubyanka, he met Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who was then a Marxist, and organised a “night university” for him in the prison, changing thoroughly Solzhenitsyn’s notions of democracy and a state based on the rule of law.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn writes in the first part of The Gulag Archipelago: “Thanks to his horn-rimmed glasses and the straight lines above the eyes, his face became severe, perspicacious, exactly the face of an educated man of our century as we might picture it to ourselves. Back before the Revolution he had studied at the Faculty of History and Philology of the University of Petrograd, and throughout his twenty years in independent Estonia he had preserved intact the purest Russian speech, which he spoke like a native. Later, in Tartu, he studied law. In addition to Estonian, he spoke English and German, and through all these years he continued to read the London Economist and the German scientific “Berichte” summaries. He had studied the constitutions and the codes of law of various countries – and in our cell he represented Europe worthily and with restraint.”

I wrote a story on that topic for the cultural portal of the Estonian Public Broadcasting (ERR) and mentioned that perhaps we should memorialise the names of Heli and Arnold Susi in the form of a human rights and democracy day.

Incidentally, I believe the archive of the Estonian Public Broadcasting as well as the articles and interviews with Heli Susi that have been published in our magazines are a great achievement of memory work, containing as they do a lot of cultural historical material. Journalist Martin Viirand, whose father also participated in the National Committee of the Republic of Estonia, adopted, with the help of Heli Susi, a mission to memorialise the actions of Arnold Susi and the National Committee during the restoration of the independence of Estonia in 1944. The actions of the National Committee were extremely important in the sense of the continued existence of the state of Estonia.

The actions of Arnold Susi, Heli Susi and others in helping Solzhenitsyn write The Gulag Archipelago were also memorialised by the late Mati Talvik in an Estonian TV programme Ajavaod [Wrinkles in Time] with a subheading “Mees, kes usaldas eestlasi” [“The Man Who Trusted Estonians”].

The Soviet regime encouraged mistrust

The Soviet regime was determined that people should not trust each other. It began with joint apartments which promoted tale-telling. Privacy was taken from people. People were collectively controlled. Curricula lacked the psychology of individuality. A lot was done during the Soviet regime to discourage close relationships. Solzhenitsyn came to Estonia and found here privacy and altruism. Friends even had to warn him that the KGB operated in Estonia as well.

I am glad that the minister of justice, Urmas Reinsalu, decided to emphasise the courage to speak out and the mission when he established the Heli and Arnold Susi Award. As we know, the current minister has worked as an adviser and undersecretary to former Estonian president, the late Lennart Meri, where he was undoubtedly schooled in preserving memories. Lennart Meri, in turn, had worked with Enn Sarv, a lawyer who worked on the National Committee in 1944 and who was repressed by the Nazi as well as the Soviet authorities.

Enn Sarv was one of the advisers for my film, Memories Denied. In the film, I tried to find answers about the nature of the malice and treachery of the regime that transported my under-aged mother to a Gulag in 1948. Sarv became my good friend as well as an interpreter of history and eras.

I was able to share with him the mindset that we must constantly define the things that make a good and caring life, the things we strive for. This new good thing can be learning new things, learning to notice life and make acknowledgement, being merciful and forgiving, in order to be the best you. According to the classic representative of psychology Carl Gustav Jung, every person represents in principle the entirety of humankind and its history. That which is possible in the history of humankind in a larger sense is possible on a small scale for every person.

Can culture save the world?

I returned to this wisdom when reading the memoirs of Arnold Susi. Last year, I met students from Seattle University via Skype who had watched my film, Memories Denied, and read the opinion piece in which I posed the question whether culture can save the world. And therefore, they asked me whether it can. I did not know how to answer because every day I look for the answer myself.

I know that my mother survived in the Gulag because she was reminded of a poem by Marie Under, or perhaps she forgot herself and sang a Schubert serenade and imagined herself in another time, a free time; when she finished, the people around her cried. Arnold Susi also writes in his memoirs that he was comforted by music, something that he was able to engage in from time to time even in prison.

Arnold Susi writes how prisoners from Estonia studied languages in the concentration camp, even though there was little chance of survival, and how he once saw fellow prisoners attentively listening to a man. This man was theologian Elmar Salumaa who provided others with spiritual assistance. He became a spiritual guide who tried to elevate and encourage his pessimistic fellow prisoners as a spiritual, yet also a dashing and witty, speaker.

Poet Artur Alliksaar, who was imprisoned and starving, asked to be sent philosophical articles from home. The popular notion today that in order to engage in intellectual things you have to be rich was not believed back then.

Stories and speeches have a deep and significant task

While I was writing this speech, the collections of speeches by Lennart Meri were on my table. As a historian, writer and filmmaker, he was masterful in telling the type of stories that change the course of history.

Among others, I was very affected by a speech that Lennart Meri gave at the 48th session of the UN General Assembly in 1993, addressing the topic of Russian forces being withdrawn from Estonia and finally talking about reforming the UN – that small countries who make up the largest proportion of all the world’s countries have the obligation to redefine the world order. His speech was successful because the Red Army was withdrawn from Estonia in the following year. If this had not happened, today we would not be members of NATO and the European Union.

What I mean by this is that the stories and speeches that we share with others have a deep and significant task. In addition to us sharing information, the things we share place us in our time and place, telling who we are and where we come from. These stories tell us how we see the meaning of life. Plato had already talked about the effect of stories on creating a country, what values and ideals the stories share.

The story of Arnold Susi and his courageous companions bound together by fate contains everything that is significant and related to our country and mentality – and is worth being passed on. Today, stories are used as weapons of information and psychological warfare in order to set people against each other, generate anger and cause shame.

“The best dish for an Estonian is another Estonian” is a Stalinist mantra

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s essay, “Estonians”, offers so much recognition and love to the people and the land of Estonia that it has a therapeutic effect in today’s world in which we repeat the Stalinist mantra created by the KGB and the late Gustav Naan (an Estonian physicist and philosopher, and a loyal communist and opponent of Estonia’s pro-independence movement – editor) that the best dish for an Estonian is another Estonian. People who lived before the war and occupation and who I interviewed do not know this saying; it is completely foreign to migrated Estonians as well. Solzhenitsyn writes about Estonians sticking together in the Gulag; he is moved by a scene from the novel, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, where two Estonian prisoners do everything together, go to work together, eat together, talk to each other and care for each other.

In the essay “Estonians”, he describes a reunion with Arnold Susi in 1963, just when One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich had been published. As a matter of fact, it had been translated by Lennart Meri and Enn Sarv who were also helped by a former Gulag prisoner, the politically ostracised Artur Alliksaar.

“Among this small nation, on this small land was cast the translation of Denisovich as a spark – the first one in the Soviet Union, furthermore, as a cheap mass edition; I remember thinking: one book per four to five families, incredibly more than in Russian. In Estonia, almost everyone had read this book – and I was surrounded here by such a homelike ambiance, general friendliness which I had never encountered in the Soviet world – and back then, Estonia was the most beloved for me precisely because of its lack of the Soviet spirit. That is why I felt back then that I would be unable to leave it behind effortlessly and permanently.”

Acting against totalitarianism irrespective of its colour

Arnold Susi fought and acted against totalitarianism irrespective of whether its colour was brown or red. Not once did he hesitate when the fate of Estonia was under question. He was an old-school person, not only an intellectual but an intellectual in the largest sense possible, accompanied by a respectful attitude towards his fellow humans.

Memory researcher and literary scholar Rutt Hinrikus has written that thinking about the generation born at the end of the 19th century, the generation of Arnold Susi, one is immediately reminded of the phrase man of honour.

One of our greatest thinkers, the late Fanny de Sievers (an Estonian linguist, literature researcher and essayist – editor), has said that a person may be educated but if he lacks that something that originates from respect towards his fellow humans – and altruism – his education will turn into an acid that will begin to destroy.

It has been said that the activity of the National Committee was connected to the Nazis. Today, the word nationalism generates ambivalent emotions, but back then it meant the attitude, “we are Estonians and Europeans”.

The old-school lawyers, Arnold Susi, Otto Tief, and the young lawyers Enn Sarv and Jaan Kross, were nationalists in the sense that they worked in the name of the independence of Estonia and democracy. Cultural researcher Ivar Tröner reminded me that the late Linnart Mäll (an Estonian historian, orientalist, translator and politician – editor), who grew up in the Soviet time, continued, whether knowingly or unknowingly, the work the National Committee and Arnold Susi started, writing down the declaration of independence for small countries and being in turn supported by Russian researchers from Moscow when the KGB made his life hard in Estonia.

Remembering is the only guide to the future

Lawyer, writer and repressed restorer of human rights Enn Sarv, who has been mentioned several times, has left us this saying as a legacy: “It is very important to remember the past again and again, to fight against intentional and unintentional forgetting because a short memory gives an undeserved clean conscience to the parties involved. Remembering is the only guide to the future that can be trusted. Therefore, remembering is an obligation.”

In recent years I have heard the opinion from those of our people who are involved in culture and politics that Estonia should not focus on its past but that we should look to the future, that we should not present ourselves as victims to the world because this would shame us, it would be inappropriately tragic.

I will talk about an experience of mine. Last year, before Europe Day on 8 May, I was contacted by the University of Regensburg in Germany. The students, who were organising Europe Day, had read Memories Denied and invited me to be the guest of honour for the day in order to discuss the darker side of humankind and the history of Estonia. Based on the experience of Estonia, we discussed the topic of what it means to be a person under occupation.

A similar question was raised in September last year in Bucharest where people of culture from the Baltic states and Central Europe had gathered. The question of what it means to be a human is very important in today’s world but in order to find an answer to it, it is necessary to know your history. It is sometimes said that history is a matter of interpretation but concentration camps, political persecution, mass murders, repressions are not a matter of interpretation but instead the dark side of humanity. Paraphrasing Freud, it is a sickness, our thoughts and world-view becoming blurred.

Director Moonika Siimets, whose film, The Little Comrade, has won several international awards, told me about a similar experience. Mankind has experienced wars, and successive generations inherit unnoticed traumas from those wars. The director talked about an experience in Korea where the viewers identified with the film’s story because they have a painful history with the Japanese, but sharing stories helps to get rid of the burden, gives a release from the victim status, creates empathy.

The novel, Pobeda 1946, by writer Ilmar Taska is similar – it reveals marvellously all the archetypes that are bred by any kind of totalitarianism. The book touches readers because these stories are the stories of all of us, and we must be vigilant in order not to let the darker side of mankind overcome us. History is not history – it is us right now; understanding history alone releases us from crimes and creates a more empathic today.

We are all in a reciprocal symbiosis with our lives, life-stories, history, achievements and contradictions of society. Our mission is to understand ourselves and follow the golden rule of life: do not testify against a fellow human being! This was also followed by Arnold Susi and those close to him, his daughter and those people such as Lembitu Aasalu, Georg Tenno and many others, thanks to whom we are free today.