When local TikToker, Ksenia Niglas, posed a question to her followers about the national identity of Estonia’s ethnic Russian population, the response was nothing short of mixed. Now, journalist Svetlana Stsur attempts to tackle the question through the historical lens of ethnic nationalism, while making a case for why it may be more damaging to call native Estonians with a Russian-speaking background Estonian Russians.

“Know thyself” is one of three Delphic maxims, moral rules and philosophical standpoints of the ancient world, which is inscribed in the forecourt of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi.

Socrates, credited as the founder of the Western philosophical school of thought, was allegedly one of the first proponents of a philosophy predicated on self-knowledge. Today, the idea of knowing yourself underpins the billion-dollar self-help and business coaching industries.

Self-knowledge is believed to help you find a dream job, get out of an unhappy marriage, earn more money, upgrade your social status, get over childhood traumas and so forth.

It is unlikely that knowing thyself will solve all your problems. However, it will certainly help find your place in society and facilitate navigating the different stages of life.

The closest sociological definition of “knowing thyself” is “identity”.

Local TikToker raises a question

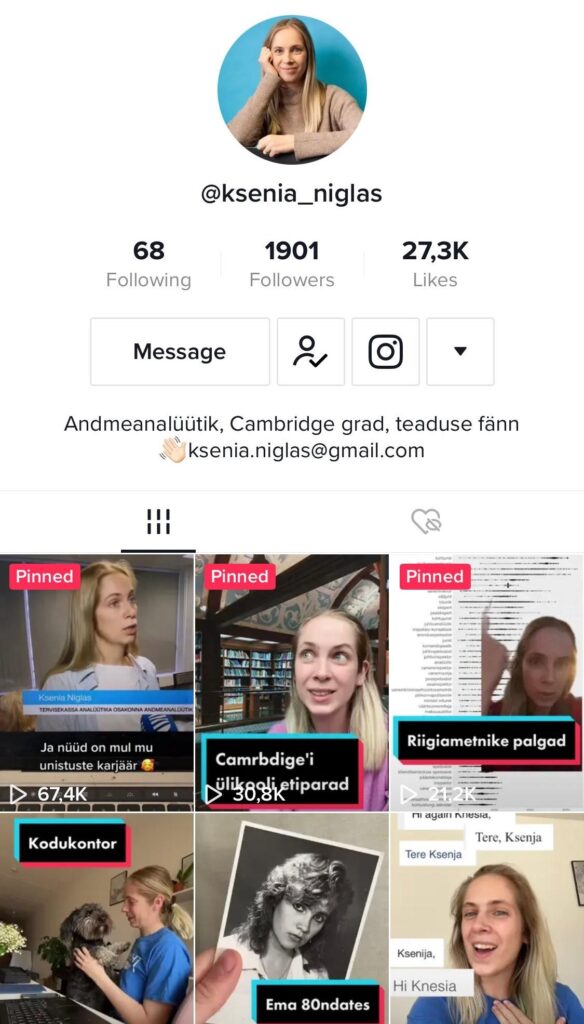

Ksenia Niglas, an Estonian blogger, shared her concern about the term “Estonian Russian” (“eestivenelane” in Estonian) with her TikTok following. Niglas said that she feels annoyed when someone refers to her as Estonian Russian, as the emphasis is often placed on the Russian part of her identity, despite the fact that she has nothing to do with Russia save for speaking Russian as her first language. As Niglas explained, “I am an Estonian citizen, I speak the Estonian language, I share Estonian values, I participate in Estonian culture.”

She went on to pose the question: “What went wrong that we began to refer to Estonian citizens as Estonian Russians based on their mother tongue? Am I overthinking?”

Needless to say, the responses have been interesting:

- “Even if a person speaks an official language of the country where they live and has its citizenship, it will not change their nationality.”

- “You are an Estonian Russian if your nationality is Russian.”

- “You are Estonian Russian if you grow up with the Russian language at home.”

- “Why do you have these identification issues? Don’t you know from your family tree which nationality you are?”

- “You don’t have that much of an accent; you can be Estonian.”

An emphasis on the mother tongue, family tree or foreign accent while speaking Estonian in the context of national identity corresponds best with the logic of ethnic nationalism. Moreover, the users who left those comments do not distinguish between nationality and ethnicity, signifying another common feature of ethnic nationalism.

Professor of comparative politics, Raivo Vetik, wrote in his article “National Identity among Estonians and Estonian Russians” that Estonian nationhood has been historically constructed around culture, and this is why being “an Estonian” to ethnic Estonians goes beyond mere citizenship. To them, being an Estonian means having a common past, a shared concern for preserving the Estonian language and culture, animosity towards the years of Soviet occupation and so much more.

Estonian Russian

The term “Estonian Russian” is often used in media and public discourse when referencing Estonia’s Russian-speaking population. However, there are many people who speak Russian as their first language but do not identify themselves by their mother tongue, and Niglas is one of them.

To overcome this inconsistency, the terms “Russian-speakers”, “foreign language speakers” and Estonian residents of “other nationality” were introduced in public documents. None of them are particularly inclusive. The term “Russian-speaker” implies that the person has no nationality. Likewise, definitions including the words “foreign” or “other” linguistically support an existing separation between ethnic Estonians and the Russian-speaking community in Estonia.

Niglas suggested using the term “Russian-speaking Estonians” as a compromise, considering it a step towards a more inclusive and civic identity. However, in the ideal civic model of nationalism, all people with Estonian citizenship should, without hesitation, call themselves Estonians. Adopting a civic Estonian national identity would bring a happy ending to the 30-year integration struggle of the Russian-speaking minority. However, there are several obstacles on the way towards civic nationalism in Estonia.

Citizenship, language and self-identification of Russian-speaking Estonians

In 2017, linguist Martin Ehala’s research on the role of language for the Estonian national identity concluded that, sadly, around two-thirds of the Russian-speaking community in Estonia feel like they have very little to do with Estonia, the country where they were born or have lived for many years.

There have been several generations of Russian-speaking Estonians born since 1993 – young people who have had and continue to have the right to obtain Estonian citizenship without taking the otherwise requisite language test or constitution exam. However, holding Estonian citizenship does not inherently orient them towards the Estonian state and society: consuming Estonian media, making Estonian friends, voting in the elections, participating in civil society activities.

Ehala’s research confirmed that primarily, a solid knowledge of the Estonian language makes Russian-speaking Estonians more willing to associate themselves with the Estonian state. Unfortunately, only around 60 percent of Russian-language school graduates speak Estonian well enough to continue their studies in high school, where 60 percent of the subjects are taught in Estonian, not to mention an exclusively Estonian-language based university education with the exception of a few English-language commercial programs.

However, the language issue is not the only problem facing a more inclusive nationalism model in Estonia. By broadening the meaning of “Estonian”, ethnic Estonians will be forced to weaken their dominant position in Estonian society, such that the redistribution of cultural capital can take place, thus improving the position of the Russian-speaking minority in Estonia.

Three moral clauses of domination for Estonians

Since the restoration of Estonian independence in 1991, three moral clauses have been identified in the Estonian nationalist studies, created to justify the dominance of ethnic Estonians in Estonia.

1. The first one is that ethnic Estonians are the indigenous population of the territory of modern Estonia.

Even though there is not an official definition of the term “indigenous population”, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People contains a modern understanding of the term. According to the declaration adopted by the General Assembly on 13 September 2007, indigenous populations are groups of people, which existed prior to the colonial era, who have strong links to their territories and surrounding natural resources and possess a distinct language and cultural beliefs.

The same declaration emphasises the historic injustices, colonisation and dispossession of lands which prevented indigenous populations from developing “in accordance with their own needs and interests”.

This definition is doubtlessly applicable to the fate of the ethnic Estonians, who have lived on their territory for thousands of years but have been wholly independent for only half of a century.

2. The second moral clause comes from the most recent generational trauma for Estonians – the Soviet occupation from 1940-1991.

In “The White Book: Losses inflicted on the Estonian nation by occupation regimes 1940-1991” by the Estonian State Commission on Examination of the Policies of Repression, Dr Heino Noor wrote that terror and repressive acts inflicted on Estonians during the Soviet occupation, including mass murders, arrests and deportations, caused permanent mental and physical damage to the Estonian nation: “Memories of violence and health injuries will be engraved in the collective memory and their results might last for generations.”

3. Finally, the last moral clause for an Estonian dominant position: Estonians are a small nation and must put a lot of effort into preserving its language and culture.

“Estonian language strategy 2021-2035” by the country’s science and education ministry identifies the major challenges for the preservation of the Estonian language. One of these challenges is that in some parts of Estonia it is still not possible to receive quality education in Estonian – a reference to the Russian-language schools, where the quality of teaching in Estonian is quite low.

Another related challenge is that Estonian proficiency among the population with a foreign home language (read Russian) has not increased in any meaningful way over the past decade. In addition, given that the language issue is heavily politicised, it is therefore difficult to implement necessary changes to educational legislation such as the abolition of Estonia’s public Russian-language education.

To move towards a more inclusive form of nationalism, it is necessary for Estonians to assess and reconsider these moral clauses, while also maybe adding some new focal points to the construction of an Estonian identity, which would in turn give a Russian-speaking Estonians a more positive reference point for self-identification.

However, for now this road seems to be particularly bumpy because of the different perceptions of cultural pluralism among Estonians and Russian-speaking Estonians. Russia’s war in Ukraine and Putin’s ridiculous justification for the invasion as an act of protection of the Russian-speaking Ukrainian residents, does not make it any easier.

Value of cultural plurality for Estonians and Russian-speaking Estonians

A significant obstacle towards reconciliation of the Estonian and Russian Estonian identities into one unifying Estonian identity is that Estonians tend to see the Russian language and culture as a threat to the existence of the Estonian language and culture, while Russian-speaking Estonians do not.

For example, in 2017, as part of the Integration Monitoring survey, when both Estonians and Russian-speaking Estonians were asked whether during the Estonian Song Celebration (Laulupidu) Russian songs should also be performed because one-third of the Estonian population speaks Russian as their first language, over 50 percent of the Russian-speaking respondents supported this idea, while among Estonians only 16 percent were in favour of it.

Another example comes from the education realm. As part of the same survey, Estonian parents were asked if they would be comfortable with their children studying in a class where kids with a Russian-speaking background comprise the majority. A dismal five percent of these parents reported having nothing against such a classroom.

Finally, both Estonians and Russian-speaking Estonians were offered a statement about the inevitability of conflict in a society with different ethnicities represented. Two-thirds of the Estonian respondents agreed that several ethnicities in one country will eventually lead to a conflict. Just one-third of the Russian-speaking respondents thought so too.

It is important to note that Russian-speaking Estonians are particularly supportive of the idea of a multicultural and pluralist Estonian society because this could improve their position in the ethnic hierarchy. The extent of desired improvements differ within the Russian-speaking community.

For Russian-speaking Estonians like Ksenia Niglas, with a good knowledge of Estonian and an orientation towards the Estonian state, it is important to find a permanent source of national identity, a clear sense of belonging to the country of her origin. Other members of the Russian-speaking community, with a more pronounced Russian identity, might find their status as an ethnic minority particularly burdensome, and dream of a societal structure where Estonians and Russians are separate but equal ethnic communities, a dream that seems to be totally unacceptable for ethnic Estonians.

Conclusion

Since 2020, the world has been living in state of permanent crisis. In the beginning of 2022, at a time when Europe had only begun to climb out of the Omicron wave of Covid-19, Russia invaded Ukraine. This ruthless invasion brought death and misery to the Ukrainian people, while also causing an energy crisis and rising inflation across Europe. Moreover, widespread food insecurity for countries dependent on the export of Ukrainian crops emerged.

One important lesson we have gleaned from these turbulent years is that it is of the utmost importance that we remain united in difficult times, whether it be through a massive vaccination campaign, creating an emergency policy for helping refugees or navigating our way through an energy crisis. In Estonia, each time we face a big issue, we are reminded of our greatest national weakness: the lack of unity between the Estonian and Russian-speaking communities.

By moving towards a more inclusive form of national identification and broadening the meaning of what an Estonian can be, we not only overcome the division between communities but also provide a sense of confidence and security to the younger generation of Estonians with a Russian speaking background. People like Niglas deserve to feel comfortable and safe when referring to themselves as Estonians, even if their first or last names are of Slavic origin and they speak Russian as their first language.

Both ethnic Estonians and Russian-speaking Estonians have to put their effort and energy into bridging the gap between the communities. Estonians will have to find the strength and willingness to forgive the pain of their Soviet past, which is inextricably linked with the Russian language and culture. Conversely, Russian-speaking Estonians have to do better at learning the Estonian language and teaching the younger generation of Russian-speaking Estonians to appreciate their ethnic roots while also loving and respecting their motherland, the Estonian language and culture.

The opinions in this article are those of the author.