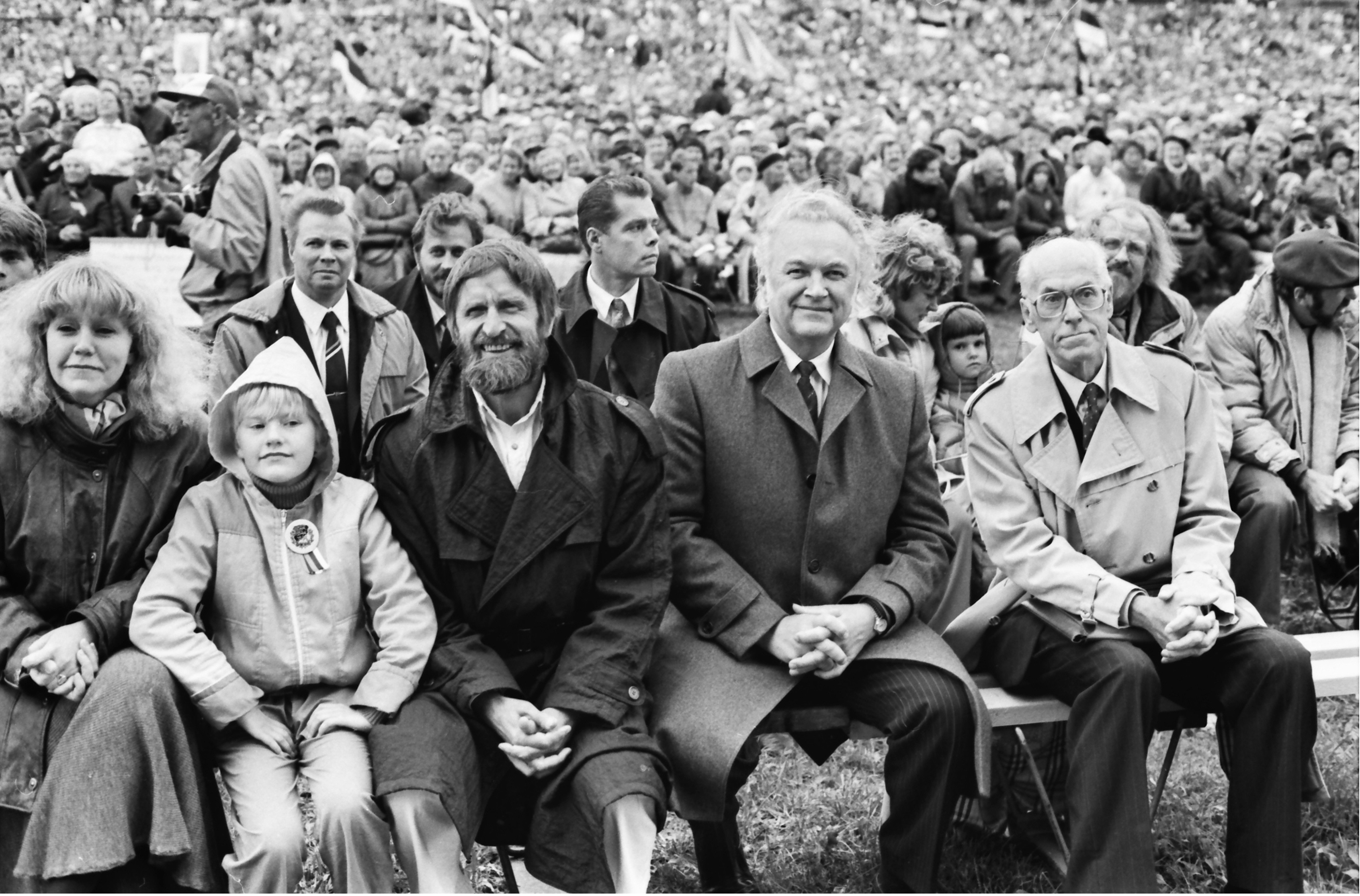

On 29 March 2024, the former president and foreign minister, Lennart Meri, would’ve celebrated his 95th birthday; a Statesman with a capital S, he’s one of the founding fathers of the Estonian post-occupation success story, and one of the politicians in Estonia that everybody truly respected.*

My best friend celebrates his birthday on 29 March, the same day Lennart Meri was born. And on many occasions, when I call him on his birthday, I don’t say “happy birthday”. I say, “Happy Lennart Meri’s birthday”. That is the degree of respect we, the people whose formative years were during Meri’s presidency, have for him. One can’t have that degree of respect unless one’s a true mensch (Yiddish for “a person of integrity and honour”).

In 1996, I sent the newly re-elected president Meri a congratulatory email. I sent it to the official email address of the president, truly expecting him never to see it. A day later, a reply came from lmeri@vpk.ee – the personal email address of the president. “Thank you so much for your good wishes,” it read. The man must’ve got thousands of emails every hour. And he took the time out of his schedule to actually write back to a young fan he didn’t know, because he cared enough.

Yes, I am biased. I honestly admit I loved and admired the man. But so did hundreds of thousands of people in Estonia – and abroad. Perhaps to this day, Lennart Meri remains the most liked, the most respected politicians that post-occupation Estonia (and maybe the pre-occupation one, too) has ever had.

The former Estonian president, Toomas Hendrik Ilves, tells me that Meri often criticised the sitting government, even though constitutionally he shouldn’t have, and Ilves believes that’s why Meri was so popular among the Estonian people. “Who doesn’t like the government to be criticised?”

A traveller, writer and a filmmaker

Another aspect to Meri’s popularity was that he wasn’t a typical politician. He wasn’t constrained by party lines because he didn’t belong to one.

He served as foreign minister in the government of Edgar Savisaar, the now-former leader of the centre-left Centre Party. But when he was elected president, he was the favoured candidate of the centre-right Pro Patria Alliance. He had broad support from both left and right-leaning people because he wasn’t a traditional politician.

Most of his life, Lennart Meri was a writer and a filmmaker. He travelled extensively, and during the Soviet occupation, also beyond the Iron Curtain, and thanks to his diplomat father (Georg Meri was a diplomat in Estonia before the Soviet occupation), he had been educated abroad. He had studied in nine different schools in four different languages, and he was fluent in Estonian, English, German, Finnish and Russian.

Already during the Soviet occupation, Meri attended the University of Tartu and got a degree in history. Unfortunately, due to the Soviet politics, he was unable to work as a historian, so he turned to arts to earn his living.

In 1958, Meri published his first book, titled “Tracing Cobras and Karakurts”. It was a travel book about his trip to Central Asia. But he’s probably most famous for “Silver White”, in which Meri contemplated, using both science and fantasy, over the past of Estonians and other Baltic Sea nations. Many think that “Silver White” is one of the most masterful disquisitions about the past of Estonians.

Lennart Meri, the politician, started to develop after he was finally allowed to travel beyond the Iron Curtain in the late 1970s. He started to establish close relations with politicians, journalists and Estonian expats and worked tirelessly to remind the free world of the existence of Estonia, and the fact that it was occupied by the Soviet Union.

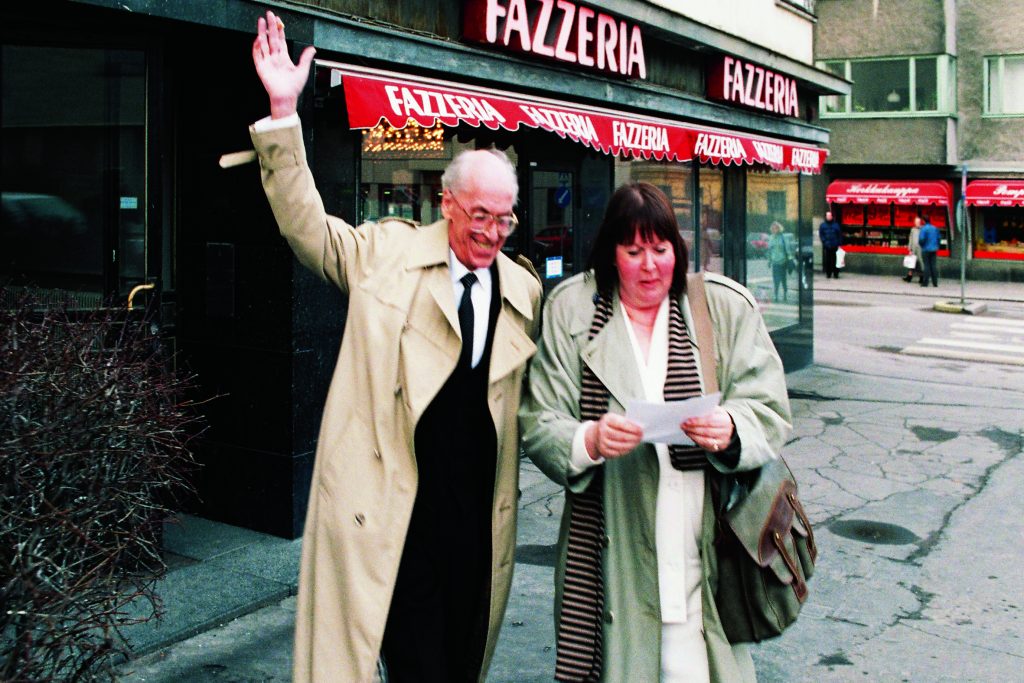

“I knew Lennart Meri from 1985. The beginning was very typical Lennart Meri-like, because I was in Finland, in Turku, and then someone set up a meeting between us in July of 1985. I drove from Turku to Helsinki or Espoo, where he was, and it was the worst rain storm ever, and he said, come at 11 or 12, so I got up in the morning. And, of course, Lennart Meri was not there. This was before mobile phones. So, I stood there at the front door of this house for an hour. Then he came an hour, hour-and-a-half later, laughing. And then he proceeded to smoke my Marlboros,” president Ilves remembers.

Rebuilding Estonia’s foreign service

“From that time on, every time he would come to the West, he would call me up and he would say, call me back, which also meant I had huge phone bills.”

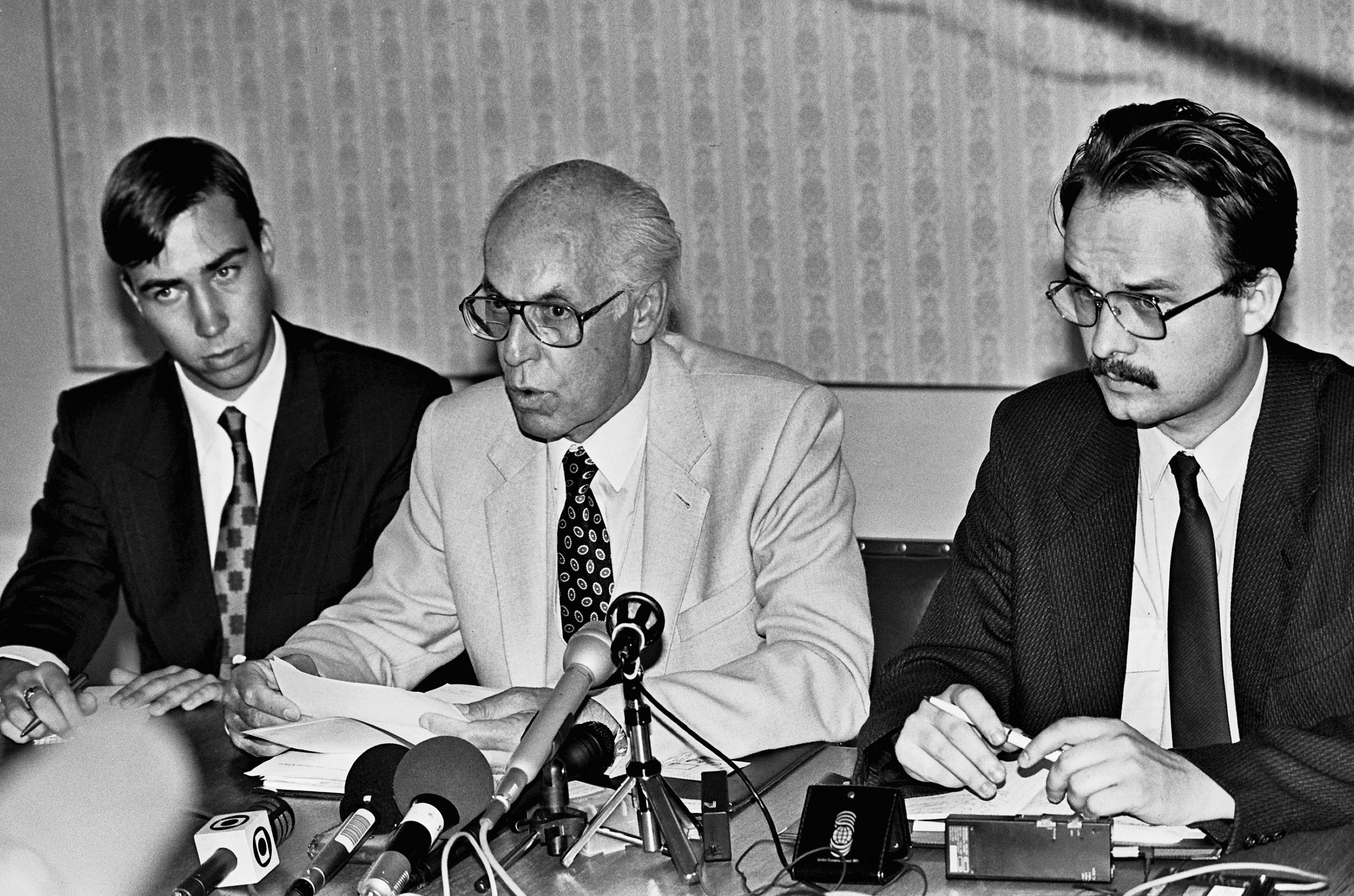

“I would help him, he would send me texts and I would send them back. I went with him, I think in 1990, to Vienna. In 1990, when the three Baltic foreign ministers went to what was then called the CSCE, now the OSCE, summit in Paris where they welcomed (the then-president of Czechoslovakia – editor) Vaclav Havel, and Havel asked that the three Baltic foreign ministers be let in, and (the Soviet leader – editor) Mikhail Gorbachev vetoed that. So, they stomped off, and since he [Meri] was the one who spoke decent English, he was the one to give a press conference. I wrote the statement for him.”

In 1990, almost two years before the Soviet Union officially collapsed – but a few years after it already started to crumble from every corner – the then-leader of the Estonian government, Edgar Savisaar, invited Meri to become foreign minister. And thus, the former writer and filmmaker officially entered politics and was handed the enormous task of rebuilding Estonia’s foreign service, Estonia’s diplomacy.

The last time Estonia had its own government and its own foreign service was in 1940. Fifty years of Soviet occupation had done its job and government-wise, there was almost nothing to rebuild on. The work had to start from the scratch.

“When he became foreign minister, the most important thing he did, which was something that other countries didn’t do, was get rid of all the commies,” Toomas Hendrik Ilves, who himself was foreign minister when Lennart Meri was president, explains. “Because the so-called ESSR (the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic – editor), the ministry of foreign affairs was just a KGB outfit. That was a policy later followed by other Estonian ministries. Not all of them, but the ones who were successful, did a clean house.”

The foreign service, to this day, looks like Lennart Meri

“The other thing that was important was that he attracted to the foreign ministry so many bright young people, many of whom actually left university to go work for the foreign ministry. There were so many of them who all came out of the sense of patriotism, and many of whom have remained there and in public service.”

One of these bright young people who at the time went to work for the foreign ministry and has stayed there for the past 30 years is the current deputy chief of the Permanent Representation of Estonia to the EU, ambassador Clyde Kull.

“The entire foreign ministry and the foreign service, to this day, looks like him,” Kull says when I ask him, what was the most important thing Lennart Meri did when he became foreign minister. “He created this ministry from the ground up, he created the principles of foreign service that we still adhere to. His approach was pragmatic, creative, constantly searching. He had this idea that things cannot flow on their own, they have to be developed, pointed to, one oneself had to be active. That sense of mission, the fact that nine-to-five isn’t important, the important thing is to get things done. This work culture, it’s all from Lennart and it still exists.”

Kull was one of the first five or six people who started in the foreign ministry. “One of the problems was that we were involved in the ministry already before the Soviet Union had collapsed. And Lennart didn’t want to deal with the old, Soviet structure. But at the same time, he didn’t have role models or examples to build up a western ministry. The ministry he took over was practically the protocol department of the Soviet foreign ministry. He started from scratch.”

According to Kull, many people working at the foreign ministry at the time didn’t actually work for the ministry but were employed elsewhere – because of the lack of structure. They were technically employed elsewhere and got paid from elsewhere, even though they worked for the ministry. The foreign ministry employed its first advisors – Kull among them – only in March 1991, which was still half a year before the Soviet Union ceased to exist.

One of the best foreign services of a small country

“The creation of the departments at the ministry and the building of the structure really started around the summer of 1991,” Kull remembers. “We created the department for foreign economic relations, the press department, the policy department and so on. It was a very creative process.”

Foreign minister Meri mostly relied on contacts. “He was constantly networking. I was sent to the Danish foreign ministry for a week, I had to sit in the minister’s office and watch how they work there, what is being done. He was eager to seek experiences and didn’t want to get that from some kind of a written material, he wanted live experiences.”

President Ilves says he considers the Estonian foreign service one of the best foreign services – if not the best – of a small country that he has ever seen. “Clearly you can’t compare it to the British Foreign Office, or the French, let alone the State Department in the US,” he explains.

“But for a small country, it has an amazing number of highly talented people who have been working there now for almost 30 years, some of them, that have a level of quality that is rarely seen in many other countries, small countries especially. That was a major step by Lennart Meri to actually start from scratch, invite the best and the brightest, and they came, and it has had a lasting impact on the Estonian foreign policy.”

Meri left the position of the foreign minister in 1992, and he was appointed the country’s ambassador to Finland. But that was a position he didn’t hold very long, because the same year, the ruling Pro Patria Alliance asked him to run for presidency. The country’s then-head of state was Arnold Rüütel, who had been the chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic, was also running for presidency, and the centre-right ruling party didn’t want to let that happen. (Although, Rüütel did become president in 2001, after Meri had served his two terms.)

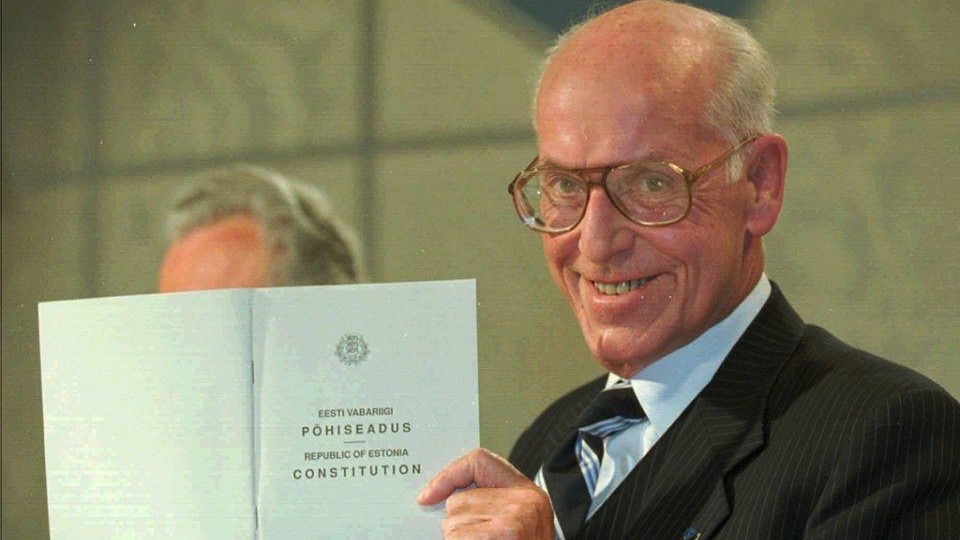

Even though in the first round of the presidential election, Rüütel had got 45% of the popular vote, the second round of the election was held in the parliament. On 5 October 1992, 59 of the 101 members of the Riigikogu supported Meri as president. He was sworn in the next day.

A number of disagreements

To this day, the post-occupation Estonia has had four presidents, two of them former foreign ministers – the other one being Toomas Hendrik Ilves.

Thus, I have to ask, is having been a foreign minister somewhat a perquisite for a successful presidency?

“It helps,” Ilves says. “According to the Estonian constitution, one area where you have genuine competence, is in foreign policy. It’s not necessarily the case that a foreign policy background gives you something as president, but certainly, in the Estonian context, it has been useful so far as foreign policy is constitutionally mandated competence of the president. Whereas many other things are not. It was certainly the case with Lennart Meri that you had someone who was taken more seriously as president than some other presidents of small countries.”

In 1996, during the second term of Lennart Meri’s presidency, Ilves accepted the position of foreign minister in the Estonian government.

“I became foreign minister because he called me up and demanded that I move to Tallinn and become foreign minister. And then he called prime minister Tiit Vähi and said, make him foreign minister,” Ilves recalls.

“We actually had a number of disagreements on a number of issues because we just saw certain things differently. But he was important for my foreign policy goal, which was that until I came, Estonia, like the other two Baltic states, thought of the European Union as a secondary matter. And my argumentation based on my experience in diplomacy, foreign policy and also in Washington was that we would never get into NATO if we were not a member of the EU. Because the EU members could veto someone from outside the EU from NATO membership. If we were members of the EU, they could not say no. You don’t veto an EU member. That was something where much of the foreign ministry didn’t agree with me, but Lennart did, so that was quite helpful for pushing that through.”

How about the disagreements? “We had disagreements over ambassadorial appointments, how long people should stay as ambassadors, because I was afraid of something called clientitis, which is that if you’re too long in one place, you begin to represent more the country you’re in rather than the country you’re from, so we had a big disagreement about that,” Ilves remembers.

“But in general, we saw things very much the same way.”

Meri steered the system, the system didn’t steer him

According to Clyde Kull, Lennart Meri was beyond patterns, standards and models. “He rather used them for a creative approach, not vice versa. Because bureaucracy and accepted models oftentimes start governing ideas and directions. He regarded ideas, directions and principles more important and he used them as instruments in bureaucracy. He was the one who steered the system, the system didn’t steer him.”

President Meri was the type of person who tended to call people one or two o’clock in the morning. “He had an interesting work style. He had a thirst for thoughts, ideas; he always had a starting point, he vaguely knew what he wanted to ask or get, but he needed input from others, and then he gathered these inputs during the night from everywhere, and by the morning, he was holding a pen, putting all that down on the paper along with his own thoughts,” Kull recalls.

“The best example of this was when we were together on his first work visit as president, to Brussels. We had a meeting at NATO. It was the first time when a Central or Eastern European president came to give a speech in front of the NATO ambassadors. And we already were in the cabinet of Manfred Wörner, the then-secretary-general of NATO, with whom we had a small meeting before going to the hall.

“The meeting was coming to an end and then Manfred Wörner suddenly felt that something was up. So he asks Lennart, is everything all right, can we go to the hall? Lennart replies, yes, principally we can go, but I don’t yet have my speech. The speech was in the hands of Alar Oljum, at the time the speechwriter, who was finalising it. The hotel was near the king’s residence in Brussels, and the driver who was supposed to pick it up had got lost on his way there. So then, Wörner sent his car to fetch the speech. We waited for a long time and talked some more until the car came back. It was the same speech that Lennart had finished writing in the early hours, and Oljum’s job was to type it up.”

A genius at learning at a very late age

“This calm quality was very intrinsic for him, but it also characterises his work style,” Kull adds.

“Lennart Meri was kind of brand new to foreign policy,” Toomas Hendrik Ilves points out. “He knew more than most people, but it was based on listening to Svoboda and the BBC. That was it, really.”

“Occasionally, I would send him books, and other people sent him books as well. He was better read on foreign policy than many other people who became foreign ministers. But it was kind of a late thing for him. He was a genius at learning at a very late age a lot about foreign policy.”

When Meri died in March 2006, I had been working as a journalist for eight years – five of them as a jack of all trades – an online journalist. Every emotion in my body had died by that time. Bad things happened all the time and when the said bad things happened, I usually sighed, worried about the fact that I had more work to do, that my weekend was ruined, that I couldn’t go out to drink that night because I had to work until 2AM.

But the day Lennart Meri died, I cried. The TV was on in the office and they showed old videos of president Meri, and I was just standing there next to my desk, watching it, and I couldn’t help but well up. The emotions that I had suppressed all these years, they weren’t dead. I just needed a personal loss, a personal affection, to release them. Yes, the day Lennart Meri died, I cried. And so did many others.

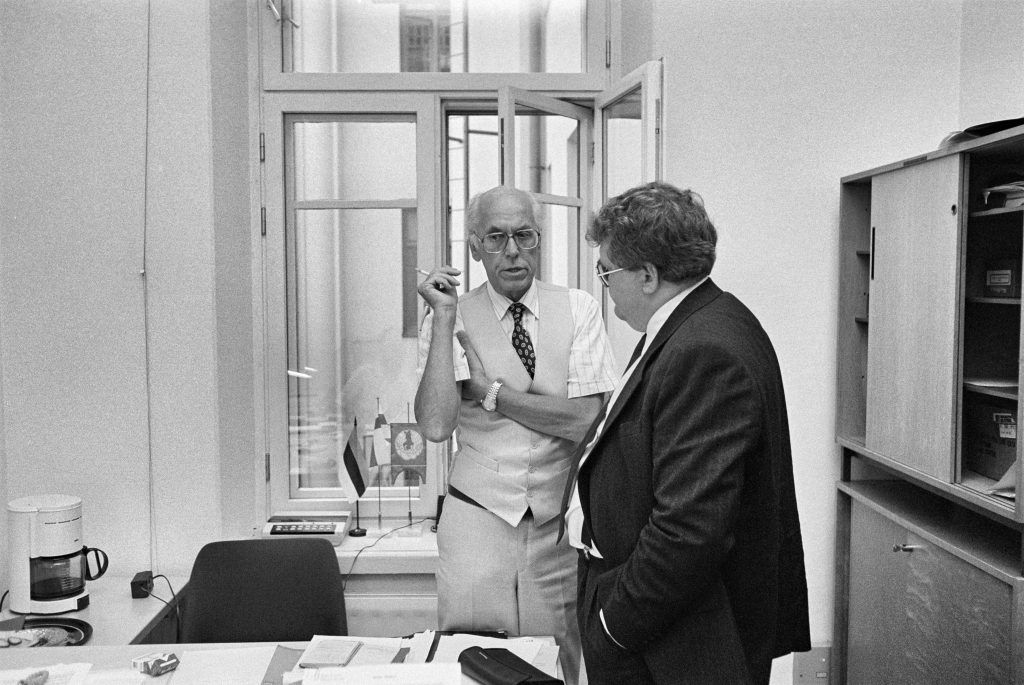

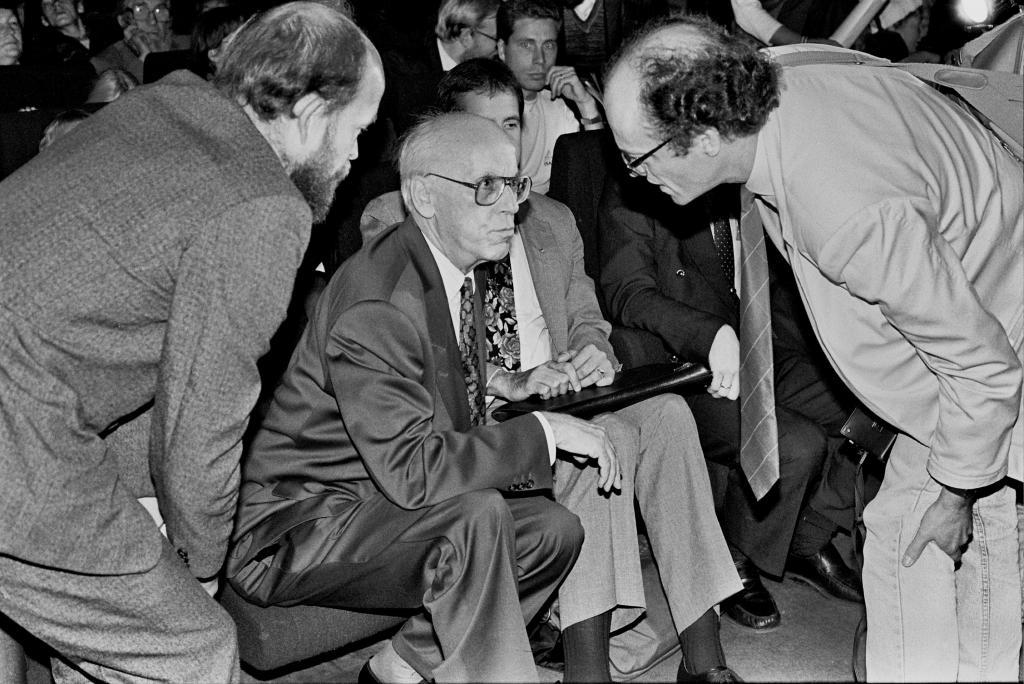

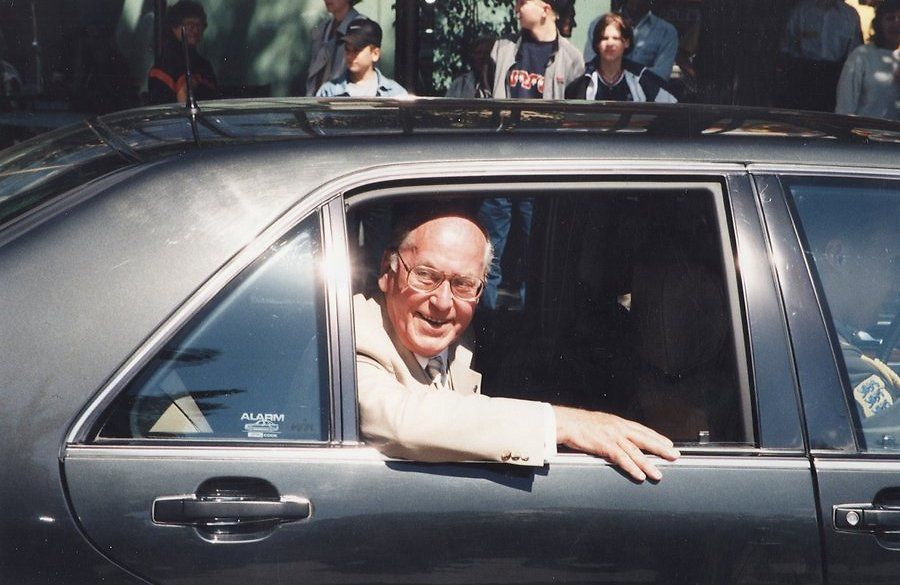

Images courtesy of the Estonian foreign ministry and © Peeter Langovits, author of the exhibition, “Thinking of Lennart Meri”.

* This article was originally published on 29 March 2019 and lightly edited on 29 March 2024.