Although older in origin, the Estonian flag was officially adopted in 1918. Is it time for an update?

When broached by the geographically uncertain and the subject is Estonia, I typically explain that it’s a small country located just south of Finland. And then, with their internal globe spinning and starting to slow, my more astute conversation partners will typically identify Estonia as a Baltic country. I respond in the affirmative, for it is geographically true.

However, I go on to explain, although we share subjugated histories and current geopolitical hardships with our Baltic kindred spirits, the Latvians and Lithuanians, the Estonians are linguistically and culturally most closely related to the Finns. For indeed, among many other similarities, the Finns and Estonians have interrelated languages difficult to master, complicated folk dances difficult to steer, and curious cuisines difficult to digest.

Which brings us to a recurring debate, at least in small circles – is Estonia a Scandinavian country? Or maybe a bit more loosely and used interchangeably herein, a Nordic country?

Clearly, Denmark, Norway and Sweden form the core of Scandinavia. But, if the modern definition of Scandinavian and Nordic includes Finland, logically Estonia has to be part of the club.

Love for saunas, check. Wife-carrying championship medals, check. Midnight sun, check. Whatever litmus test applied, whether itchy woollen sweaters, accordion music or favourite adult beverages, Estonia is of the same acidity as their Scandinavian or Nordic neighbours.

Both Nordic and Baltic at the same time

Much like the wave-particle duality of light, Estonia is both Nordic and Baltic at the same time. Photon and wave at once; Scandinavian and Baltic simultaneously – all depending on the perspective of the observer. A Nordic wave from crest to crest, a Baltic particle from edge to edge. Call it the Estonian ethnic dichotomy.

Now, a tie that binds the Scandinavian or Nordic countries is their flags. All variations on a theme, essentially differing only in colour patterns, the flags feature a horizontal cross aligned along the latitudinal. The short side of the cross, making up the longitudinal, is oriented at the side nearest the flagpole. Some feature a solid cross, others a two-tone silhouetted cross. All are identical in the unity signified.

In addition to their flags, another shared characteristic of the Nordic countries is a tumultuous contemporary history with the Soviets. Estonia, of course, took the brunt of this all-too-recent Soviet decimation. The Soviets illegally occupied. They deported thousands to Siberia, destroying families in the process.

Not as ruthless, but significant still, the Soviet Union removed the Estonian flag and replaced it with the hammer and sickle. A symbol of pride and hope unceremoniously swapped for an unwanted symbol of despair and hate.

Modernising the flag toward the north and west

A flag is an emblem of a nation state – symbolising so much more than the individual fibres woven into its multicoloured cloth. In Estonia’s case, the tri-coloured layers of blue, black and white, depending on interpretation, depict sky or freedom, soil or homeland and purity or soul.

The hammer and sickle, floating on a blood red background, may have had a benign original meaning uniting the hammer of industry and the sickle of farm peasants. However, crazed by inane ideology, the Soviet flag became an anti-flag and the hammer and sickle morphed into symbols of brute force and severed liberty.

So, what would be more emblematic of Estonia’s true place among 21st century society than modernising the flag toward the north and west?

Vladimir Putin is rattling his sabre in no uncertain terms. Longing for a past that must not be allowed to return, Putin is already planting his modern flag on the ancient sovereign soils of others.

Luckily part of NATO and a good friend of the West, Estonia has tangible and material deterrents to its neighbour’s aggressions. But as Estonia’s flag officially turns 100 in 2018, maybe it is time to institute a symbolic deterrent.

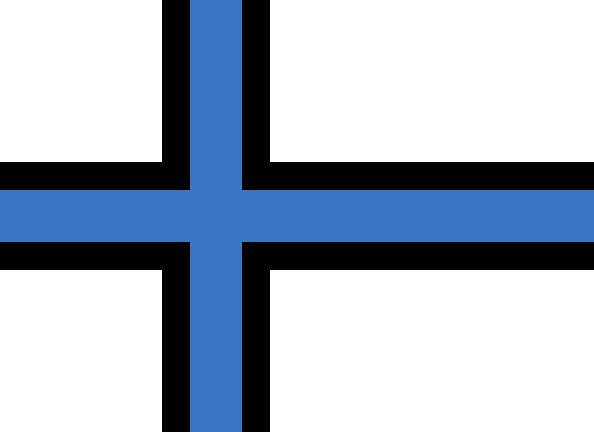

Maybe a grand 100th birthday present is in order. Not a three carat diamond. Not a three tier birthday cake. But rather a new tri-colour flag in the form of the Nordic cross. One that holds to tradition with colours intact, but proudly proclaims Estonia’s heritage in fact.

The opinions in this article are those of the author. * Please note that this article was originally published on 4 June 2015.

I like the first flag in this article. It has the blue-black-white in the right order and looks sexy af

I also like the first flag option, it is fresh, but still very Estonian. I think it is a very creative version. I am a first generation American with an Estonian Mum.

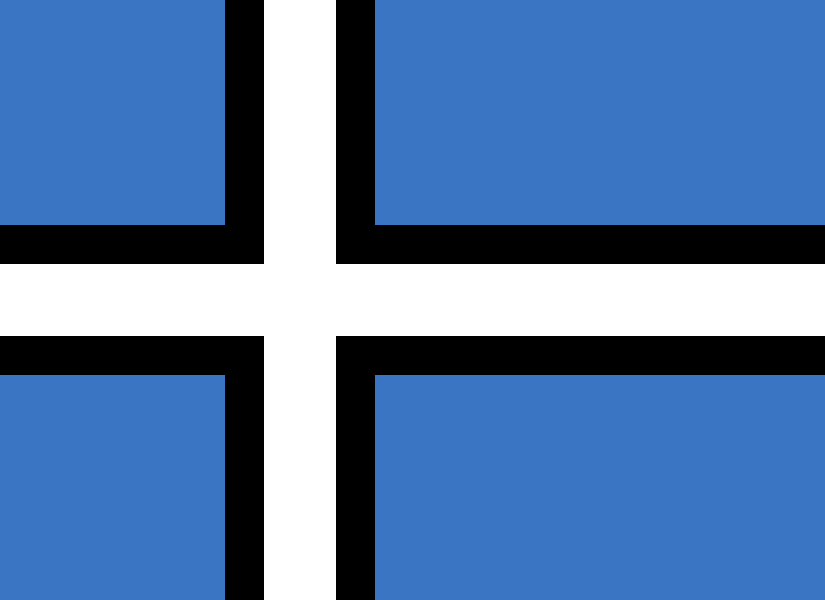

I like the third one. It’s more balanced and harmonious. I’m Brazilian, and my mother was Estonian, from Tallinn.

I like the first flag on this page. It still has the sini-must-valge symmetry with the better defined Nordic cross. I am first generation American (even my brothers were born in Europe).

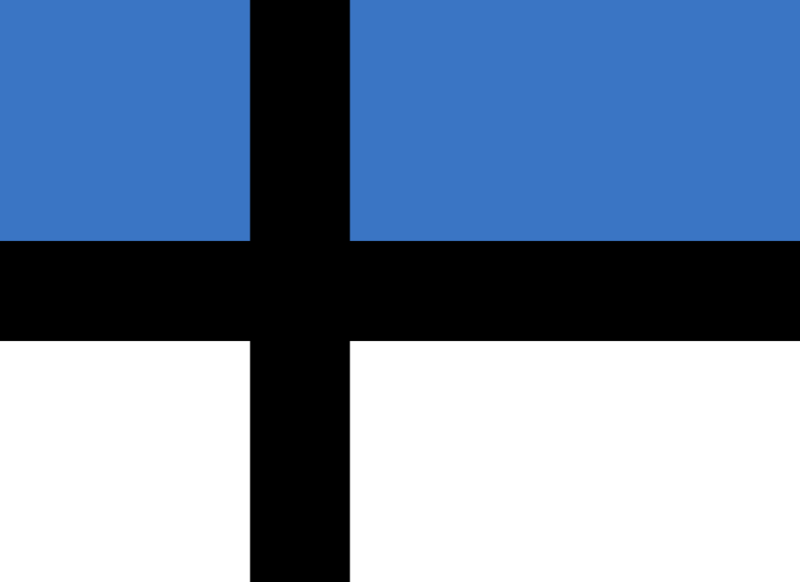

jeg gjerne velger andre eller fjerde. I prefeer second or fourth, they ar more nordic like. Nordisklige. Som Faroese

Please do not change my flag. My mother Mai was born under it in 1923. My grandmother Mari was hauled off to Siberia by the KGB in 1948 and died there in 1954 yearning for that flag.

I met my Estonian family, for the first time ever, under that flag in Tallinn in August 2014. And my daughters will be visited by my second cousin when he flies to the United States for the first time in his life in July 2015 when he departs Esti under that flag.

My daughter Mari was so proud to do a report on Estonia and that flag when she was in 5th grade after never having the chance to meet her grandmother, who died 9 years before she was born.

Some things are meant to be forever and not revised on an anniversary like a trade marked commercial symbol in the United States.

Please don’t change my flag.

As with other commenters against any change, again, your opinion is sincerely respected. My family has similar stories under the flag, as do so many. I understand where you are coming from. But to equate my post with McDonald’s changing the golden arches is unwarranted. In fact, little is forever. Historical precedence abounds for countries updating their flags.

Some things *should* be forever.

Please view the comments on Facebook regarding your article.

Hi Caroline. Indeed, I have read them all… and the counter opinion was entirely expected and is respected. But, social media posts do not make a scientific survey. By that token, I could point in the favor of my opinion to the 1,000 plus likes between the article and the Facebook post (while also acknowledging there unfortunately are no dislike buttons)… just saying.

Good try, but there’s nothing tangible in your selling points.

So, case in point… what do you think would be the response if someone dared to suggest that America’s flag should be changed…?

This is a no-brainer… leave well enough alone.

In it’s simplicity, the existing flag is an awesome design… and so easy to spot in a forest of waving flags.

Thanks for chiming in. A matter of your opinion, but sincerely respected. In response, this has nothing to do with Old Glory and need not be framed as Estonia vs. the U.S. And to completely dismiss my points, while at the same time insisting your opinion in a “no-brainer” defies logic. Sorry, but no-brainers, if there were such things, would be limited to involuntary reflexes like blinking and breathing.

I think that ‘Cross’ effed up the People. Keep those blazes of colour, they have a psychic resonance to our Estonian DNA. Amen.

The Estonian flag is older than 1918, it was first used in 1884. While I appreciate the sentiment of your proposal, turning Eesti symbolically to the west, I don’t think changing the flag is appropriate.

Symbols are sacred and deeply personal. The current flag is beloved by evey Estonian and has tremendous historical and emotional significance. The right to fly the flag was banned for almost five decades. There is no Estonian who would voluntarily pull down the old tricolour and replace it with the above examples. Not after all that was lost. Not after the struggle to fight for our right as a nation to fly it again.

That the tricolour flies again is symbolism enough that the Soviet Union was defeated. Many people never thought they would see if fly again over Tompea. The current flag represents so much more then the Nordic cross. That it continues to fly until it’s 200 birthday would be the gift most Estonians would appreciate the most.

So no thank you. I’ll continue to wave the flag that today proudly flies in Tallinn, Narva, Tartu, Parnu, and Brussels. You don’t mess with a good thing and Eesti has got one hell of a flag.

Estonian flag is 131 years old, so there is no reason to celebrate its 100th anniversary in 2018. Dr Karl August Hermann thought of this colour combination of blue, black and white for the Estonian Students Society in 1884. His idea was that an Estonian with a pure heart stands on the black soil under the blue skies. For this purpose the tricolour is the best design. The cross design does not convey the idea.

Some things should remain sacred. I think we should respect the history of our tricolour more. Some people have risked their lives trying to preserve it during the Soviet times or suffered prison sentences for displaying the flag under the occupant regime.

Your article stresses some interesting points, though. How Scandinavian or Nordic we actually are? Which is the decisive aspect – the geographical position or belonging in the same language group as Finland? Well, all other Scandinavian countries but Finland have Germanic languages, so this cannot be the decisive criteria.

Im proud of our flag as it is. Cross on the flag, big no from me. Gross on the flags, which is the main symbol of christianity and most of estonians dont belive in any religion.

Ma sydamest loodan,et meie lippu ei muudeta.praegune lippu disain on ilus.need ristid on maru “religious” Ja minu maletamist mooda eestlased pole suure usuga.

This is as silly as the US of A or GB would change their flag into a tricolor.

To see our flag rise up as the anthem is sung is a proud feeling that swells the chest of every true Estonian. This flag is what our nation is. This flag is very beautiful flag. To us, this flag is Freedom!

To change the flag is to spit on the suffering of our grandparents and their parents who hid it for so long and more often that not suffered for it.

As our Republic of Estonia is direct descendant of the country created in 1918, it inherited its territory, flag and people.

To change something as personal for a nation, as a flag, is appalling and unprecedented. Flags change when regimes change, when empires fall and nations rise. One does not simply change a flag into something “cooler”.

Where did I write that change would be based on a hipness factor? And this would not be unprecedented, with Canada being a good recent example. Not all flag changes are for the reasons you cite. Beyond that, your opinion is noted and respected – thank you for chiming in.

Rather than focusing on “updating” our flag (which is already uniquely Estonian, with its history, colours, and symbolism), perhaps the more appropriate discussion to have on the eve of our nation’s 100th, is one focused on “updating” our national anthem, to something uniquely Estonian? “Mu isamaa on minu arm”, anyone?

The cross has to do with religion. Estonia is proudly THE least religious country in Europe, and as some polls show, even in the world.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Importance_of_religion_by_country

So, doesn’t add up.

Well, yes, the other Nordic countries are pretty unreligious aswell, but that wasn’t exactly the case when they got the flags.

And yet they have not changed them.

Um, you are not getting my point. Neither should Estonia. Especially not into something that was done for religious reasons and is kept mainly because of tradition, because we have neither for this motif.

But those countries have indeed gone through several flag iterations over history… it is only the most recent versions that have not been changed in a while. Besides, regardless of the original significance of the cross, and while it is still symbolic of religion of course, their images have many contemporary connotations. Again, as I’ve tried to express in other comments, your opinion is respected.

The Danish flag, the Dannebrog, is where the cross comes from. It supposedly was a sign from God saving crusaders from the Estonians. Looking at this from an Estonian perspective, not sure this is the kind of historical connection one would want. Head Lipu Päeva.

we don’t need the cross. we need our original flag to live as long as possible. period.

Andres, are you deliberately stirring the pot with this article? The first flag looks like something the 20th SS would have stencilled onto their tank destroyers. I think if you consider countries that have changed their flags in recent times (like Canada) or are thinking about it (like Australia and New Zealand) the main motivation is to move “away” from a previous position, such as colonial subjugation. Your idea is interesting but I can’t detect a strong motivation towards it from any of the correspondence. One of the options would make a good festival flag or could be the basis for an unofficial national flag, much like Australia’s Boxing Kangaroo for example.

No, Sven, I’m not trying to stir the pot (but of course knew it would draw strong opinions). I was just writing an opinion piece that goes along with my personal cultural affinity and observations. As for the specific proposals, I’m not a fan of the first or second examples. But if the Wikipedia page from where those images were drawn is accurate, this concept was already proposed in 2001 by an Estonian politician. Clearly it would seem though, it went nowhere. I understand the other flags went away from something, by why does that stop one from going toward? Anyway, just an opinion piece. Interesting last take in your post – about an unofficial alternative flag.

What about this:

Dear author, I must say that I absolutely agree with you. I don’t think there is any Baltic connections in Estonia to the other Baltics. It’s history is hundreds of years of Scandinavian rule. The closest country to Estonia in culture would be Finland. However, between Tallinn and Helsinki, Tallinn is more Scandinavian. Helsinki has its own kind of charm but Estonia’s history, especially Tallinn’s is tied in with Denmark pretty strong, it’s also has a lot of Swedish influence. Estonia’s probably got more ties to Denmark then Finland considering the fact Estonia was controlled by them and has always played copycat from those. Estonia has disregarded its neighbors. The only relations for it and Latvia and Lithuania are the Soviet occupation and part of Russian Empire since 18th until 1918. In those ages, Estonia was not being affected its culture much. I have been to both city Riga and Tallinn, and I think Estonia is very culturally different than Latvia and they are almost two allien world compare to each other. I know how Estonians had to sacrifce, I know Estonians weren’t allowed to have that current flag, but proudly kept in their homes as a form of defionce and it has beeb through so many things like wars, the Singing Revolution, etc. But in my opinion, the foundations of history and culture made Estonia has strong ties with Nordic and made it has own kind of charm are more important. They created Estonians’ spiritual, created symbols of Estonia like wife-carrying contest, sauna,.. I don’t understand why some Estonians refuse Estonia is Nordic and refuse the cross flag. With me they have refused Estonia’s culture values. What about Tallinn-Tanni-linn- the old town has been recognized by UNESCO because Dannish and Swedish’s architecture?What about one of the highest church in the world was built by Norwegian king? What about the coat of arm? What about Tartu university-the symbol of education of Estonia? What about Estonia’s language which it very close to Finland’s language? What about Estonian cuisine with a number of contributions from the traditions of Scandinavia? What about the Danish flag, the Dannebrog, is where the cross comes from? Now Estonia’s financial is denpended much on Sweden, Finland and there is a strong friendship between Estonia and Nordic Council. Are they still refuse all? I think they should- of course SHOULD change the flag or at least still remember Estonia is Nordic! Thank you, your post is amazing!

Yeah, I don’t see the point in changing the flag, but I do like the first and third images as you scroll down. I think Saaremaa should adopt one of those flags and break off from Estonia and become a sovereign city-state! We Saarlased are more Scandinavian than the mainlanders because of our history with Sweden. (I say this as a proud Saaremanian American.)

Come on, Saarlased! Unite! Let’s become Estonia’s Monaco!

It would be a tremendous update for our Estonian identity as a Nordic people. But it’s a difficult decision as the current flag is full of history and blood was dropped and many was killed in order to preserve it, but the Nordic identity is equally part of our history. I like the current flag, it touches my heart whenever I see it, but If we ever change it, I would opt for the first flag on this page, because it matches the tricolour order, but I would have a small change to it, which is to make the cross a little slimmer like the other options. Estonia is clearly a Nordic country, why not update the flag then? The opposite is also true: why change a flag that has been serving us so well and we have many feelings for it? Touch decision! I would support a national referendum on this matter. Making every voice in the country heard is what democracy is all about and we should also fight to make this nation one of the most democratic in the world!

I wholeheartedly support the idea of a nordic cross flag. As a young Estonian born after the soviet union, I define myself as nordic and the flag represents that identity.

I don’t feel much connection to the current horizontal design. I do feel a connection to a cross flag.

Whatever your political opinion is…that last flag is badass.

How about adopting an Estonian nordic cross flag as the colors of the international Estonian community? That way every person with Estonian roots could identify with the homeland, while giving a nod to the Western orientation and increasing Nordic sensibilities of Estonia. While not taking away the historic Estonian tricolor.

Ahh No, the Baltics should all be full Nordic members, but keep their own flags.

The idea of Estonia being culturally and historically closer to Finland and Sweden than to Latvia, and the accompanying representation of Russia as wholly alien, is very tiresome. I’m all for Estonia choosing liberal democracy and alignment with Western Europe over the corrupt authoritarianism of most other post-Soviet states. But that doesn’t need to involve avowing any and all links with Russia and the rest of Eastern Europe, or exaggerating Estonia’s similarities to Scandinavia.

Of course there are clear ethnic and linguistic similarities between Finns and Estonians, and the periods of Swedish and Danish rule left their marks, but there’s no reason to privilege these periods over Russian rule. On the contrary, the two centuries in the Russian Empire and the half-century in the USSR were longer and much more recent than the time under Sweden. Logically, therefore, they are more decisive in shaping modern Estonian society, culture and identity. It seems pretty obvious to me that the nation most culturally and historically similar to Estonia is Latvia. The trajectory of their histories has been very similar since the Northern Crusades in the twelfth century, and today both states face a very similar set of social, geopolitical and economic issues. Not to mention the fact that their cuisines are almost identical (and a lot closer, in my experience, to Russian food than to that of Finland, Sweden or Denmark).