Kaili Colford, an Estonian-Canadian author, draws on her family’s history, including her grandmother Eha’s escape from the Soviet-occupied Estonia, to preserve these stories for the future generations.

There are some regrets you can’t undo – those that, no matter how much you want to, you can’t make right. That’s how I feel about not asking my “vanaema” (grandma), Eha, more about her traumatic escape from Soviet-occupied Estonia. She passed away last year from an aggressive cancer after battling dementia for several years.

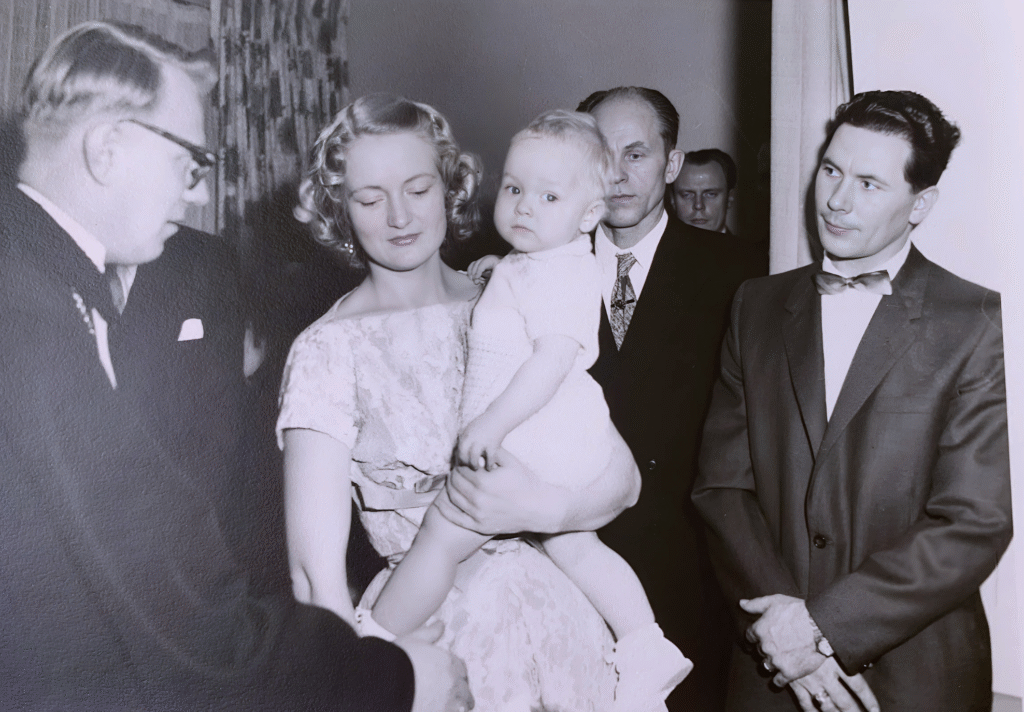

Like many Estonians who fled during the Second World War, she rarely spoke about what she endured. I imagine she kept it locked away, focusing instead on building a new life. And she did – Eha created a beautiful life in Toronto, raising three children, including my father, Mart.

Back to the fall of 1944, Estonians faced a dire choice: stay in a Soviet-occupied country, with memories still fresh from the previous Russian invasion – the torture, deportation and fear – or flee in often unseaworthy fishing boats across the Baltic Sea, risking their lives. Among the 10 per cent of the population who fled in those autumn months 80 years ago were all my grandparents.

A childhood marked by separation and struggle

My vanaema Eha was sent to live with a couple as a young child because her father was gravely ill, and the couple, unable to have children, took her in. How painful it must have been to not live with her two brothers and sister as a little one growing up.

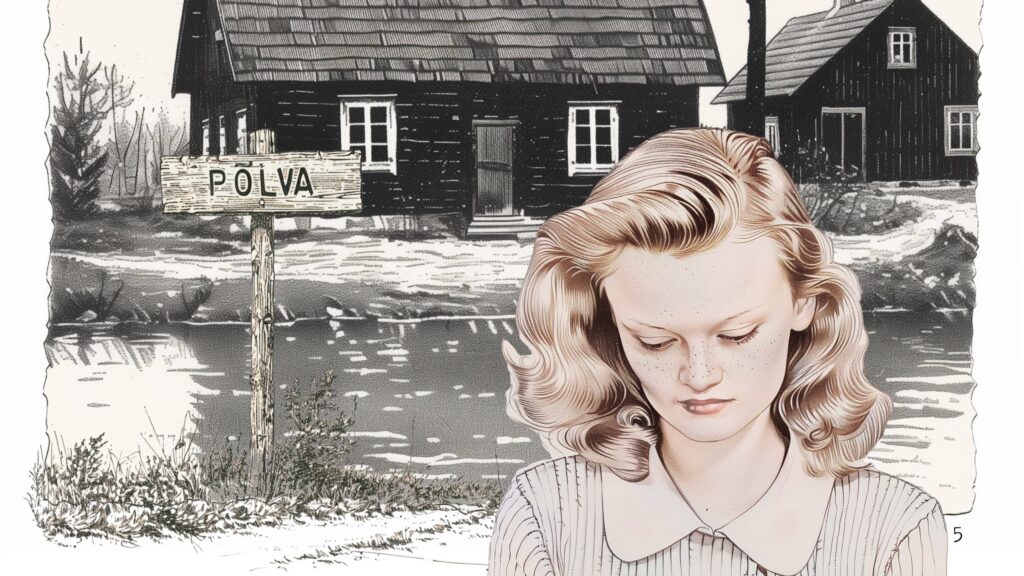

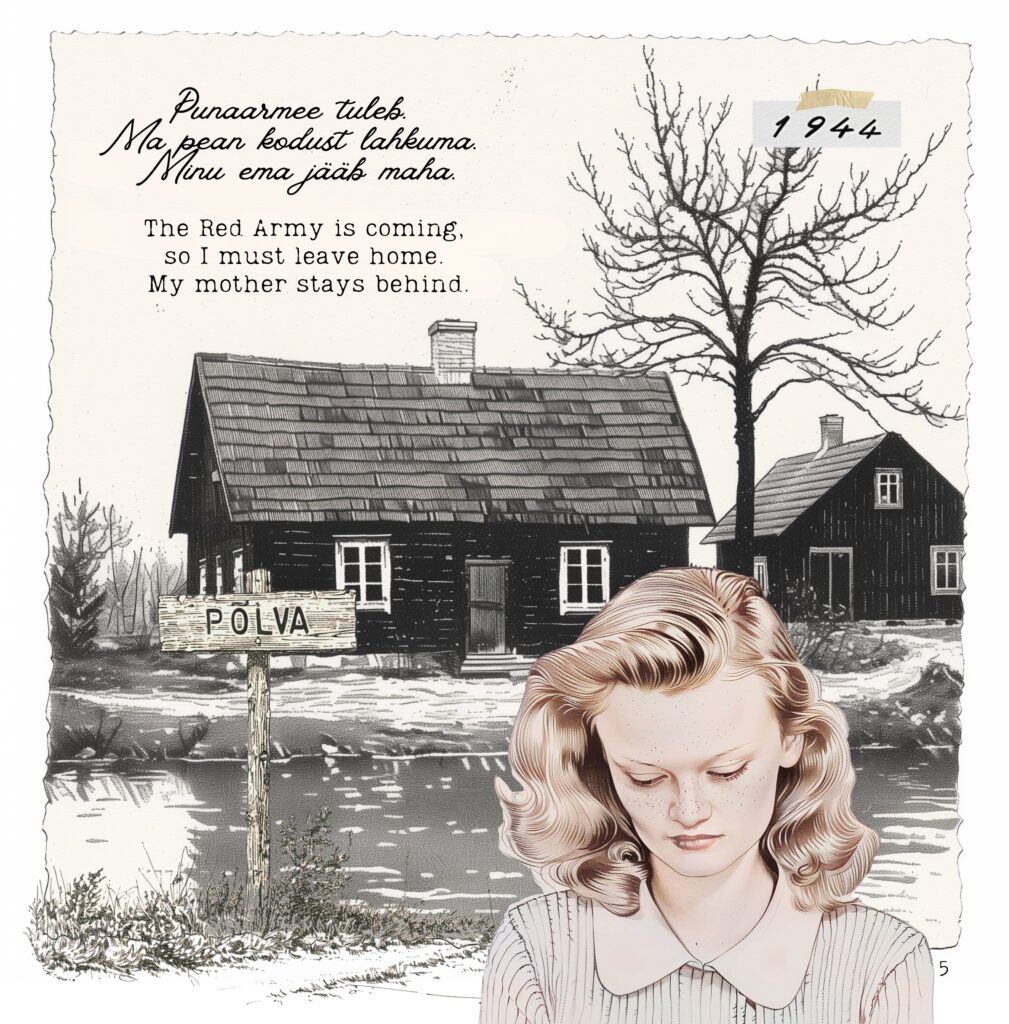

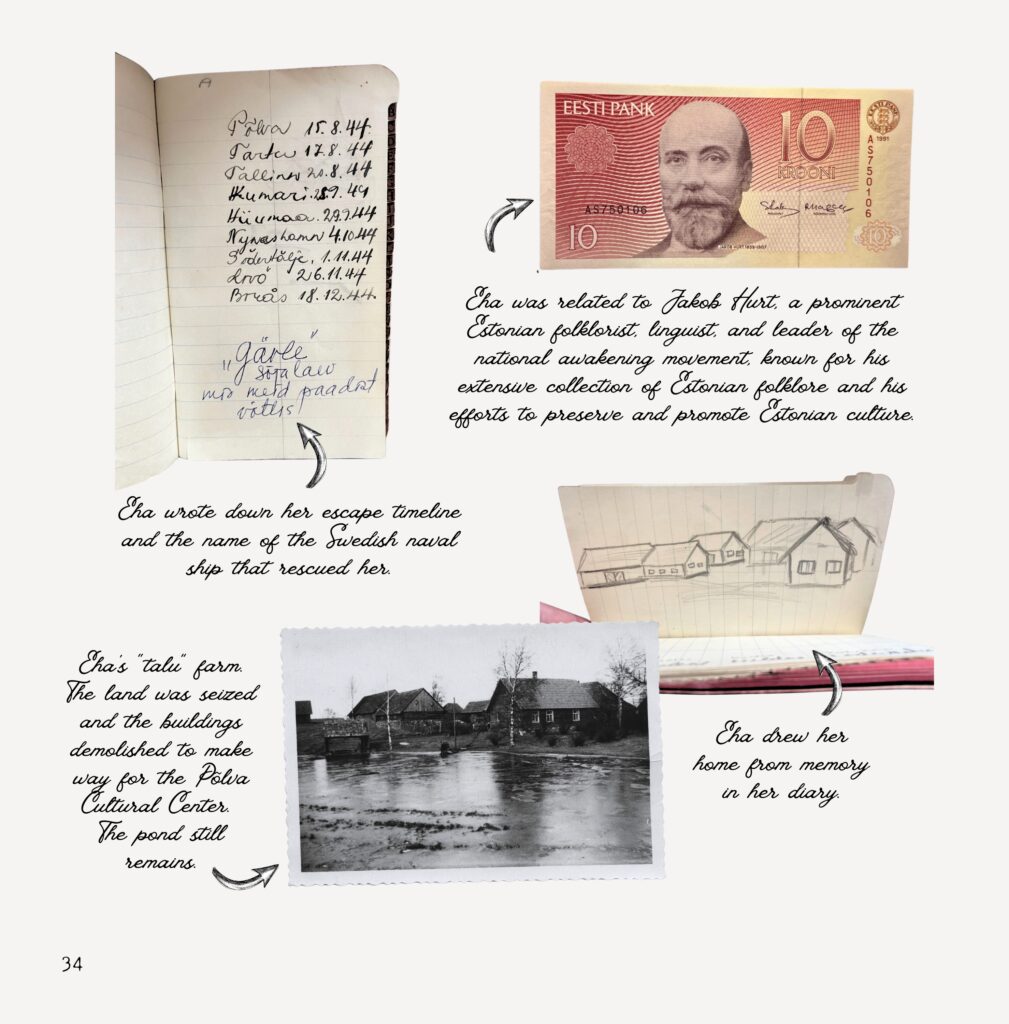

At 16, her adoptive mother died and she was sent back to live with her birth mother at their farm in Põlva. And then soon after being reunited with her original family, at the age of 17, the Red Army began to advance further.

Eha, who had dreamed of finishing high school, packed a small suitcase with a ham for her sister Erika’s family and some personal embroidery, possibly a tablecloth. Her mother stayed behind as Eha set off on her bicycle, hoping to escape alongside her older sister in a nearby town.

She pedalled until nightfall, when a farmer stopped her and asked why she was alone. She then spent the night in his barn and continued her journey the next day.

As she neared the town where her sister Erika lived, a retreating soldier stopped her and asked why she was travelling alone. He warned her that the town had already fallen to the Soviets and advised her to head to the train station, where her brother – a soldier he knew – was helping with the evacuations.

At the station, her brother managed to get her bike onto a crowded train. Onboard, Eha met another girl, and together they travelled to Tallinn, the capital, where they stayed in her brother’s apartment while sorting out their escape. An older couple offered to help them, and their perilous journey continued from there.

I never really knew all these details growing up. It wasn’t until I had children and started thinking more intentionally about how I wanted to pass on our Estonian heritage that I began reflecting on what memories had been recorded.

What could I tell my kids about their history? What sacrifices had been made by those who came before us? How could I make them feel connected to their identity and culture, even if they weren’t born in Estonia? I wasn’t even born in Estonia and neither were my parents.

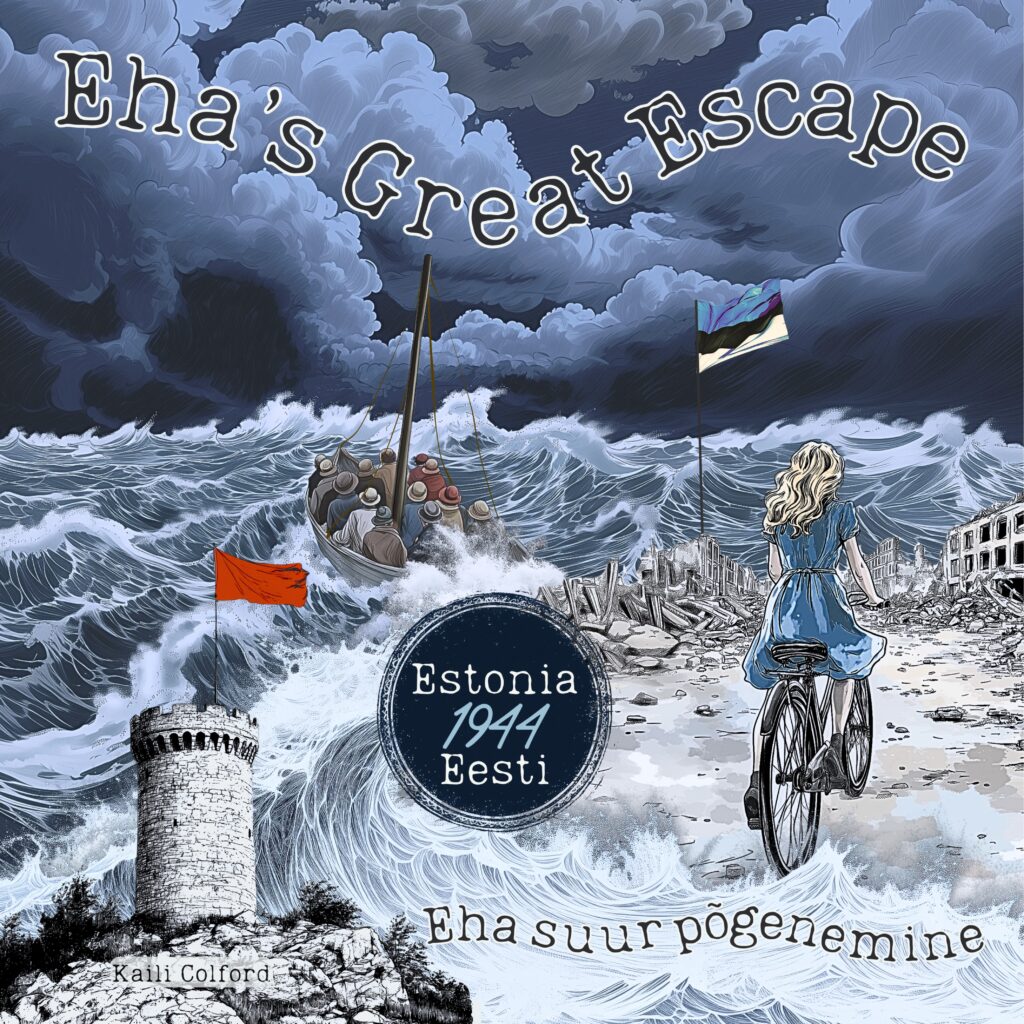

Honoring Eha’s journey through a bilingual picture book

That’s why I created this bilingual picture book, Eha’s Great Escape (Eha suur põgenemine): Estonia (Eesti) 1944. It’s not just a history lesson – it’s a reminder that history is never far behind us.

My husband is Ukrainian-Canadian, and as I see the current fight for freedom in Ukraine, I’m reminded of the struggles for survival and sovereignty that my grandmother endured. It’s a stark reminder of how history often repeats itself, and why it’s so important to be informed and honour the past.

I wanted the book to be visually appealing and true to my grandma’s story. The imagery looks just like her and it is told like her diary because we do have a small diary of hers which chronicles her escape timeline and includes a drawing of her family’s farm from memory (both are featured in the book).

This was my chance to give Eha a voice – this gentle, soft-spoken matriarch could now show my children and the world just how brave she was. Through simple diary entries, page by page, her story comes to life.

Readers will feel the emotions of what it must have been like to board those overcrowded fishing boats, face terrifying storms and grasp the reality that friends and classmates may be lost to the same sea. They’ll imagine huddling together on desolate islands, inching their way out of disaster, all while being cold, seasick and shot at by Germans in the night.

Sometimes, when we mark anniversaries like the Great Escape, or when we witness ongoing atrocities like those in Ukraine, people can be dismissive. They argue that we should focus or celebrate the brighter moments in history or accept that things can’t change, claiming we dwell too much on the darker days.

But that mindset really frustrates me. If history is bound to repeat itself, we must ensure we are informed. We need to honour the past by sharing our ancestors’ struggles with younger generations – so they understand what it truly means to fight for freedom and why it can never be taken for granted.

So, I’m starting with Eha and this book, and I’ll create more because this story isn’t just hers. It could be any of our relatives. So many of us are displaced or have ancestors who were, and lucky for me, all of my grandparents survived their escapes.

While I regret not talking to my vanaema more about her struggles, this book is a way to share her story with the world. Her voice is finally being heard – loud, clear and powerful.