An artist is often less universal than a creative businessman, says Marko Mäetamm, an Estonian multimedia artist, who works within the mediums of video, drawing, and the internet.*

Mäetamm studied graphic art at the Estonian Academy of Arts and also studied practicing print technologies at the Swedish Royal Art High School. He has had solo and group art exhibitions throughout the world and has published two books, one under the pen name/moniker “John Smith” – a fictional conceptual persona occasionally used by Mäetamm as an alter-ego in his artistic projects – often, in collaboration with fellow Estonian artist Kaido Ole.

Veronika Valk interviewed Mäetamm at PointB Roof Terrace in Williamsburg, USA.

What does creativity mean to you? It is such a worn out word.

I believe it is ability. And that you are born with it. You cannot get it out of nowhere, you cannot learn it. I have met people in whom I have not detected the slightest ounce of creativity and who do not understand the process, how it works, how you can create something that did not exist before. The ability to collect ideas from the world around you and spawn something out of it.

For me, creativity is accompanied by curiosity, a heightened desire to exhibit yourself. Creativity entails a field that could be defined as communication with others. I do not believe in the kind of creativity where you keep creating and only for yourself – that is something different. It is rather more like you create and you want it to spring to life. And it springs to life thanks to a special kind of observation, sensitivity – perhaps there is no creativity anymore and it is more likely a sum of all the things listed above. A process comes into being and that process is creativity.

If you look at creativity directly, you will not see it. However, if you look away, you will notice it. For instance, if you look at the keyword curiosity, you will begin to see creativity. Or you think ‘playfulness‘ and from the sidelines, from the periphery, you will sense that it is creativity. It is a tiny island that is born in the middle of it all out of the sum of various traits of the person. A grey murky soup, a puddle. Don’t know why it is there but if you possess certain traits, it leads to greater creativity.

In terms of your living environment, can you name some specific traits where this soup of yours is brought to a boil?

My creativity starts flowing well in an overpopulated crowded environment. I need to be by myself, but I like it very much when there is a powerful information background, be it audio or visual or something else. I need that noise, but I am not staring at it, I am not consuming it. I feel it with my skin somehow. And then things get moving inside me. I start getting strange thoughts, stories, visuals, ideas that may not be precisely linked to my surroundings of that moment.

Environment excites me, it is my acupuncture, makes me tingle inside. Things don’t move around inside me this way in some quiet place, in a forest, in the nature. Actually I do not understand people who go somewhere in the country, a farm, and start creating there. I need to struggle with a nervous environment, in a positive sense. When you are pushing and shoving in a crowd, you walk around and hear the noise of the traffic, the rumble all around you, everything starts working.

At the same time you have said about your experience of being in India that it was horrible. Yet you were also in a noisy environment there?

Yes, I was, but it was horrible in terms of everyday living conditions. I had difficulties with adjusting and had a culture shock, but I was working very productively there. I really liked working there, but the everyday conditions were so radically different, put me under such pressure, made my life so difficult that it was horrible. Although paradoxically, it had a great effect on my creativity!

Perfect living conditions are not essential in terms of creativity; for me, it is important that I am sort of pressed between something, within a dense body that at the same time allows me to be alone in there, so that I am not constantly with someone. Being by myself, going to crowded places – urban environment is good for me.

The creative process you described, which includes being on one’s own – is the creative process therefore individual? There has been talk about such a thing as collective intelligence.

Of course it is collective – there are so many ideas that emerge in parallel. I think there is a certain field full of signals. I don’t even want to know where these signals come from in that field, but people with slightly more sensitive antennae pick them up. You pick up the right one. An enormously concentrated environment is a good thing because it is so dense. Quite literally – everything is up in the air. And if you have the talent to catch those things from there, then yes, I believe that there is a collective field, an information bar.

Are there any other cities where you would like to explore, see, feel that information bar? A place where you haven’t been yet, or have already been to but would like to visit again?

I have a very warm relationship with London, I have been there many times and would go back in a heartbeat, any time. I feel very open and productive there. Although it is a significantly calmer environment. At the moment I feel that this more nervous New York suits me even better. Before I came here, I thought that the best place for an artist to function is indeed London. At the moment, though, I can admit that New York is even better. Although in London I would also feel that I am swimming in the right pool.

My ideas often first appear verbally rather than as a visual image – they appear like a sentence, someone said. Therefore, it is important that I am able to communicate in the local language. Although Paris is great and nice, even though somewhat more languid, I do not speak the language, which means I spend more time on my own there, I am not connected to the surrounding field. Making contact with the language is important. That only leaves English-speaking environments where I can understand what people are mumbling. I have never been to Tokyo…

Most of your works are in private collections, you mostly exhibit them in galleries – how would your works work in public urban spaces?

A difficult question, my files usually fail to open on that issue. I have made one public space work, in Cardiff, Wales. The assignment was to interact with the city space. That was difficult. I accepted the challenge and was even satisfied with the result; however, I must admit that this chapter was closed again.

I cannot activate myself as an artist in urban space, I am more of a gallery artist and I can perfectly imagine my ideas being expressed in a book. The space must be internal, with a limited environment, where I am interacting with a closed space. I am not able to fathom urban space to the extent that I can add something to it. I consume it like an environment that is a maze, but I do not walk around going ‘WOW! I could make something here’. For some reason, the thought never occurs to me.

Will the future world be ruled by creative superheroes?

For quite a while already, the business world has been ruled by people whose creativity levels are above average and who are curious about creating as a phenomenon. They are doing better. Those with less creativity are doing worse. You can go a certain way with little creativity, but then you hit a limit and yes, those superheroes are the people who keep going further.

Whereas a businessman has the skills necessary for working in the financial world, the trouble with artists is that they usually only have that creativity. An artist is often less universal than a creative businessman. The artist is usually handed one talent, his or her creativity handed as a large chunk, a segment, leaving all other fields as mere gores on the sides, making it difficult to operate in the society.

Family is often in the centre of your works – how do you see the family of the creative superhero of the future?

As a creative person, you are never a harmonious family member. In one way or another, you are always isolated in there. Otherwise you would lack the ability to observe from the outside, you would simply live a certain role, a model; there would be nothing to think about. On the other hand, having a constant perspective into family life while not being in the middle of it, being absent, you can see – for me, the existence of family as a model in the society is both the source and solution to problems.

My works are linked to a way of life that is family life, but the family of the creative superhero of the future could be more liberal. The orthodox family that I look at from a critical angle as a fossilised typical model of father-mother-two-children (in ideal conditions, the two children are from different genders for perfect balance) – that model becomes more and more questionable.

In the information age, the interaction of families is completely different – you can only communicate via texts, you can only exist on the computer screen. It can be virtual, but it exists nevertheless. And in that case you can have several families at once. The new channels that we have employed to exchange information have dramatically changed the existing model.

In that case, does the information and influence of school become increasingly stronger? What would the school of the future look like?

Based on the experiences of Estonia, education is the most inert and slowest field. Which is a reversed situation – it should be the most dynamic, the fastest-changing, most creative, because it has to constantly start people up. In Estonian society, education is rather pushing, pushing in any direction it wants, which may not be the direction life and other developments are taking. You constantly have to argue with it, rock it.

School and education must be able to adapt to changes as quickly as the society is generating them. Technologies and modes of thinking have changed so quickly that schools as institutions look very slow in comparison. In order to make education flexible and personal, it is interesting to think that it used to be personal once. In terms of the field of arts, people used to learn with great gurus and masters.

Today, the concept is reversed – outlet-based teaching methods are not guru-based but learner-based. This paradox has led to a deadlock that must to be broken. On one hand, the individual approach is emphasised, on the other hand, it can be taught in a really small group, via a personal approach, one-on-one. At the same time, it is impossible to approach your students individually when you have a large group on your hands. This situation inevitably leads to devaluation and the teacher must impose one vision on ten, a hundred people, who all expect to be taught in slightly differing ways, or need slightly different methods to attain that special something that they seek in schools.

The teacher is forced to choose one rake, with more or less fine teeth, but still just the one rake. This is what happens as long as schools have to get by with a small number of teachers and a great number of students. This is where finance and economics come into play – basic knowledge only allows the teachers to use a very wide rake.

People need a more individual way of learning. There are many examples of autodidacts who grow independently, with the help of materials they have studied via computer, and who may not need schooling as such simply for acquiring basic knowledge and skills. Right now, there is a chess genius around, a sixteen-year-old Norwegian who allegedly became so good because he learnt chess and constantly practiced by playing against computers not people. He found his way and went along it, even further. If you can recognise at some point which person needs which input, it is a different concept all together – only for you and only this.

The school of the future must probably develop in the same way. It is technologically possible today, after all – one person can do everything, from start to finish. Or to connect via media/digital channels to other individuals, and in that case, be able to create something that only factories used to be able to create. It is an interesting time of individualisation – there are lots of people and the population of the Earth is growing en masse, at the same time, people are becoming more individual. It will be a while before education is able to digest that paradox. There is a struggle for new ideals, but unfortunately in old conditions, ‘in the way it used to be done’.

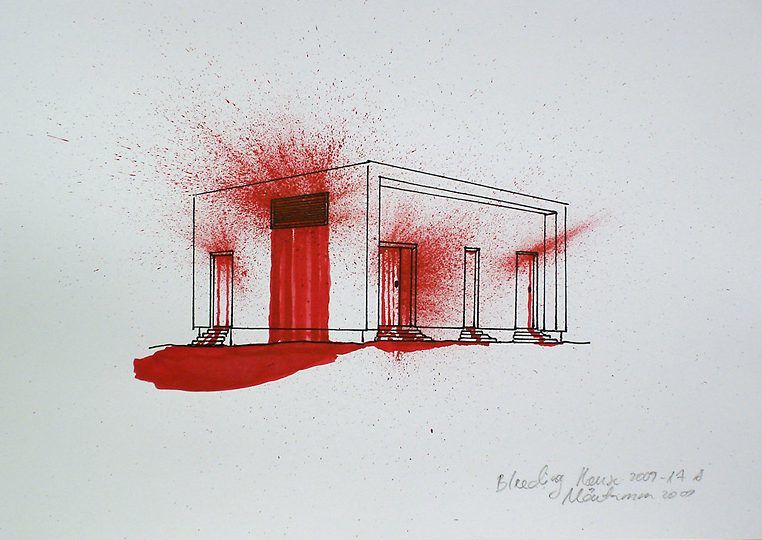

Cover: Marko Mäetamm. Images courtesy of Marko Mäetamm. * The original version of this interview was published on 20 November 2012. The article was amended in October 2016.