Estonian World talked to Teele Dunkley, a UK-based Estonian filmmaker, about her life and work and her upcoming movie project, “The Secret Folk Dancer” – a film about the Estonian-Filipino Rein, who discovers a group of Estonian folk dancers practising in London, and joins them in secret, knowing that his cool skateboarding friends would not approve of this hobby and the new community of dance friends of various ages.

In Estonia, Teele Dunkley, who comes originally from Põhara village in Pärnu County, is probably best known for directing the music video, “Vihma loits” (“Rain Spell”) by the Estonian folk music group Greip, back when she had freshly graduated from the film school in the UK.

Since then, she has made several films, receiving awards at film festivals and acclaim from Steven Fry, an English actor and broadcaster. “Losing Us”, her short movie about refugees and human trafficking, has been selected for screening at the International Human Rights Film Festival in Albania from 18 to 23 September 2023.

Now, she is raising money for her next movie, “The Secret Folk Dancer”, via the Estonian crowdfunding platform, Hooandja. Arguably the first feature film in history that has Estonian folk dancing at the centre of it, the movie is about a 17-year-old Rein (played by British actor Kim Last), who discovers a group of Estonian folk dancers practising in London.

He joins them in secret, knowing that his cool skateboarding friends would not approve of this hobby and the new community of dance friends of various ages. Rein’s dad (played by Estonian actor Reimo Sagor) is Estonian and mother Filipino and what starts off as Rein’s simple wish to dance and connect to his dad’s culture, very quickly becomes a double life that he is struggling to maintain.

The movie’s executive producer is Nick Barton, who produced the UK hit comedy feature films “Calendar Girls” and “Kinky Boots”; the Dutch producer Lesley van Dijk is also on board.

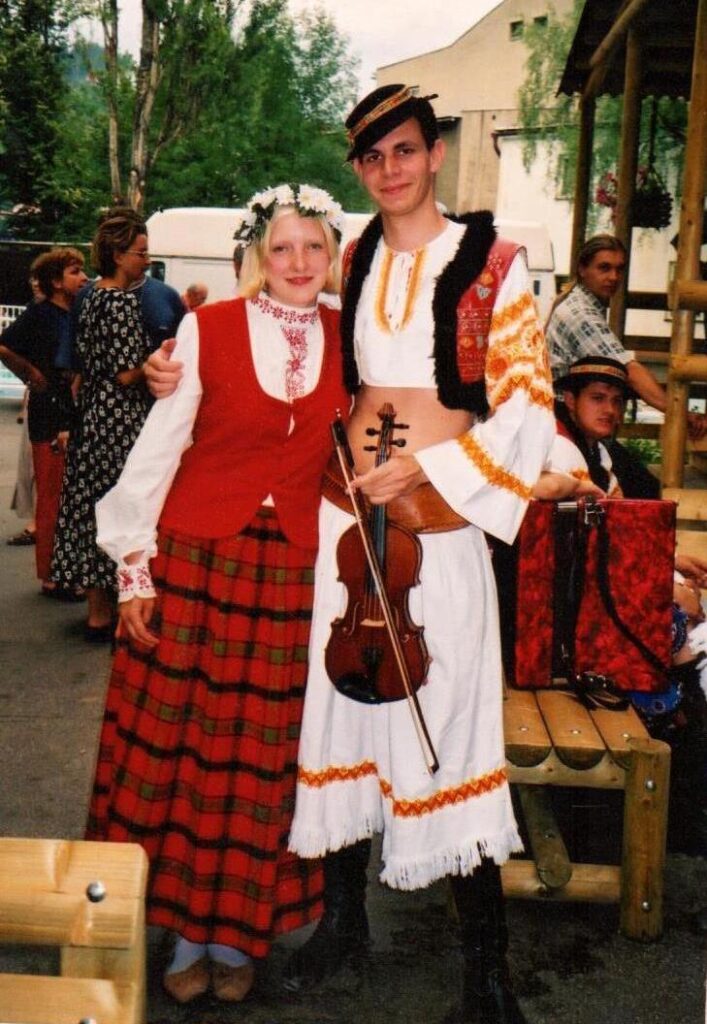

The spark of the idea for this film was born years ago, when Teele met an 18-year-old English Morris dancer who revealed that the dancing made her happy, but she was too afraid to talk about it to her friends as they made fun of her when the subject came up. Not only is the Estonian dance style very different from Morris dancing, so was Teele’s experience of growing up in Estonia where there is a lot of pride and appreciation for the traditional dances and clothes.

Estonian World spoke to Teele about the movie and her life and work in Estonia and the UK.

Can you tell us about your childhood in Estonia, and how that played a part in inspiring you to write a script for the movie?

The more I think about it, the more I see I have used some elements from my childhood as an inspiration for “The Secret Folk Dancer”. I guess that is only natural as our lives inform our creative work.

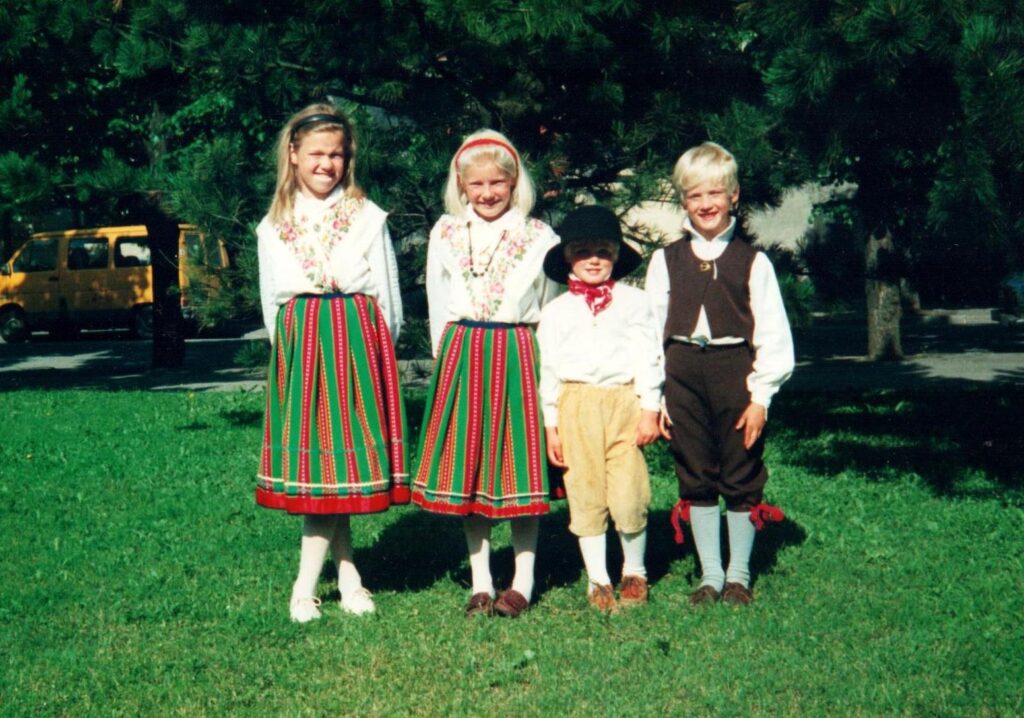

I had a wonderful childhood on a little farm, with a big family who always engaged in the folk dancing and sang. They all worked hard in various jobs, and we all worked together on the farm, too. I attended to music lessons, sang, played instruments and did a lot of dancing, and had wonderful teachers and friends.

There were some hard times, too. Our home burned down when I was 11 and our whole family was left homeless. At school, I was bullied between the ages of 12-14.

But no matter what happened, our family and I had a whole support network of people to fall back on or take our mind off things. Many of these friendships were formed in folk dance groups, singing in choirs or playing music. This feeling – being part of a folk dance group – is so much more than just a dance lesson, is one of the themes we explore in the film. It is a very social thing and they become your second family.

In 2005, I met an 18-year-old girl in the UK, who told me she loved doing Morris dancing (English folk dance style) and it made her very happy. She also told me she was hiding it from her friends because they always made fun of that style of dancing. I remember thinking I would use this as a spark of an idea in a film one day.

In Estonia, folk dancing and keeping our culture alive is a lot more respected and cherished, so the experience really fascinated me as it was so different from my own – but the idea of being made fun of and bullied is something I knew very well.

Then in 2022, I taught some Estonian folk dancing to my then nine-year-old daughter Lumi’s class at her school in England. I showed them YouTube videos from the Song and Dance Celebration of Estonian children – the same age as they were, dancing the routine we were learning at. They were so impressed by the many boys and girls dancing together in a stadium. Everyone loved the dance lessons and my daughter felt a whole new connection to Estonia and pride for the culture. It inspired her to make more effort with learning the language.

So, I thought it was about time I started working on the script for “The Secret Folk Dancer” and after first writing it on my own, I got a cowriter Stephan Drury involved, who has become a great partner to be working with on this feature film.

You are a photographer, film director and scriptwriter. So how would you introduce yourself to someone you just met? Can you tell us about your artistic journey?

I introduce myself as a film director in most instances now, but yes, I do work as a photographer and mostly photograph dancers and actors. Scriptwriting is something I have only been doing in the last few years and I have won awards for the short film script of “Metres Apart”.

It has been really fun to see people’s positive reactions for “The Secret Folk Dancer” script as it is the first feature film I have ever written, and I loved working with Stephan on it. My biggest strength with writing is coming up with concepts that make good films. Writing alone can be very lonely, but writing with others is not only a more fun way to work, but you also get to great results quicker as you bounce ideas off each other. Sometimes the other person pushes you to think and come up with ideas that sparks from something little the other person says. I love that feeling.

I knew I wanted to be a film director when I was 17, but decided to seek out life experiences before making movies, so I would actually have something to say, some stories to be told. I left Estonia at 18, I did a volunteer course for nine months in England, teacher training for two months in Denmark and then volunteered for six months in Malawi.

In 2005, I moved to England, where I worked at all sorts of jobs and, one day, I just felt it was time to move on and follow my filming dreams. I was then 24 years old and I went to study for a degree in media and moving image at the City College Norwich. We learned everything from film making, animation to TV studio production.

After graduating, I initially made music videos as a freelancer and also worked for film company Eye Film, who headhunted me out of university, after seeing my graduation film. I worked for them doing anything and everything from camera work, editing and production co-ordinating.

As I grew up dancing, singing and playing instruments, the world of music videos was a very comfortable world for me to step into and a great way to practise directing and making your vision come to life. After about a year of working for Eye Film, I took the plunge and became a full-time freelancer.

About 20 music videos later, I took a career break to raise my daughter and worked more as a photographer and did occasional filming projects when it fitted around family commitments. When the lockdown hit and everything slowed down, it gave me a chance to reset and I started to work on writing scripts and developing film projects I wanted to make, so I can get back to my dream of being a film director and here we are.

Now that you are currently raising money for your movie to happen, what is your pitch to support the filming of the movie?

When people watch films, they want to discover something new, to enter a world they have not seen before.

For Estonians, folk dancing is part of the fibre of what makes Estonia what it is, we almost take it for granted at times. We have designed this film to reach audiences around the world, to whom seeing Estonian culture will feel like an undiscovered gem. They can draw lines and parallels with their own cultural experiences as well as what it feels to follow your passion in life, no matter what others think of you. It will create interest in Estonian country and culture.

But this movie is so much more than just about folk dancing. There are a lot of moving and also funny scenes and we explore the themes of friendship, multicultural families, community and acceptance. We want to make a film that will be watched and cherished in years to come and you can be part of that journey with us.

It has been heartwarming to see how many people have been sharing the crowdfunding campaign and donations have been coming in, but we still have a way to go to reach all the money we need for the project. Funding is the hardest part of the whole process of filmmaking, so we are forever grateful to everyone who has contributed, no matter how big or small the amount is. What they are giving is so much more than money – they are telling us and the world that what we are doing is an important project.

It seems that folk dancing is very popular in Estonia. Why do you think that is?

I think folk dancing is popular in many countries around the world where there has been some sort of oppression in the past; the need to keep your culture alive at all costs is a great motivator.

Beyond that, I do feel the big reason why it is still going strong is the outlet that the Estonian Song and Dance Festivals give. It keeps it appreciated by everyone, not just practised at small village parties. It keeps the culture not only alive but evolving. The new dances and music created for each event make sure that the folk dancing is not stuck in the past.

The new influx of kids through dance groups is good but something I do not see happening at all in England for example. Folk dancing there is mainly for the older generation.

This year, the Youth Song and Dance Festival took place in Tallinn again. Did you participate at the festival during your school days in Estonia?

This is probably my biggest regret in life that I have never been able to take part in the big dance festivals. I have done the singing one and I have performed in the regional dance festivals. I was never in a folk group when one of the festivals came around. For some years, I was focusing on other styles of dancing, like ballet. I always thought – I had time, I would try to see if I could go to the next one; then, my life took me outside of Estonia.

We have been joking with some of the “The Secret Folk Dancer” crew that we want to put a dance group together and compete for the Estonian Dance Celebration (due in 2024), so maybe we can do that, and I can tick another dream off my list.

I did go and see the youth celebration this year and it was incredible to see so many young people performing. I felt very proud of Estonia and even more inspired to make our film.

How has your movie making evolved over time? Was there someone or something that inspired you initially?

A lot of the projects I had done previously were very low budget and I had to constantly think on my feet, solve problems, find help or locations for free to make things happen – particularly making videos for indie bands who had only enough to pay my salary and absolutely nothing else. Now, I can work differently and can pass my vision on to camera crews rather than having to run around with the camera myself. Having to do it all at first was an amazing experience and made me a very resilient and resourceful filmmaker.

When I was about ten years old, there was a late-night programme on the Estonian TV that was showing behind the scenes clips of how movies were made. I remember so well how I sat there watching it, while my whole family slept. I was in awe of the artistry and how miniatures became huge cityscapes on the screen and how effects were made. It seemed like an endlessly fascinating world. I didn’t even think at the time I could actually be making films as a job; it seemed something very exotic and far away.

I loved taking photos from a very early age and when my family got a film camera, I made home movies and even some crime dramas as a teenager with my friends, Merilin and Kristel. I was a terrible actor because I kept laughing a lot. In one of the scenes, I had to play a pregnant woman who was in pain. Kristel played a drunk violent husband while Merilin filmed us in a style of news crew coming in to see what has happened. I was supposed to lie on the sofa in pain but kept laughing so much because the others were such convincing actors and it was all so hilarious. So when we swapped and later I had to be behind the camera I felt much more comfortable there. I would probably be a much better actress now, but I am still sticking to behind the camera side of things.

I do have a favourite movie and that is “The Eternal Sunshine of a Spotless Mind”. No matter how unusual it is, it feels like one of the most real love stories; I love the acting, the filming, directing and the costumes – just everything about it.

Do you think AI and technology in general will help or harm the film industry? Will it change things so much we need a new term for the “film industry”? Will it distort or lessen the role of the movie director?

I have tested out of interest an AI programme with my Spanish friend Javier who knows more about it all. I wanted to see what all the fuss was about, and we tried to see how well the AI could write a comedy scene. It was terrible! Yes, the words were there but none of it was funny, no matter how much extra commands we added to it.

It is a worrying time for the industry, but the machines cannot still make us feel deep emotions or do folk dancing for that matter. But in all honesty, I am so wrapped inside “The Secret Folk Dancer” project that I have not had the time to keep up with all the AI news. Maybe when I emerge from the editing room one day, I find that robots have taken over the whole world and I would have to start explaining to them that folk dancing is important. So let’s hope that does not happen and I don’t think they would care.

How is it for a woman filmmaker in the British film industry and does it in your view differ to Estonia? And as a foreigner in the UK? Has that somewhat changed for you after Brexit?

There is a big push for female and diverse filmmakers and directors in the UK. I have previously felt a bit baffled about this issue as I never felt, or maybe never let myself feel, that being a woman has held me back in life. However, when I have attended film events or hired crew members, I can see why this is happening – it really is a very male-dominated world.

I cannot speak for the Estonian side of filmmakers but what I see from being outside of it, is great that Estonian female directors and producers are making a name for themselves.

Being an Estonian in the UK has never held me back; if anything, it is a source of lots of fascination by people as there is not much knowledge about our little country. Interestingly, what people have heard about are the good education and childcare systems and there is a lot more news in relation to Estonia now that Russia is attacking Ukraine. This is also why we decided to make our film now as any stories from the previously Soviet-ruled countries and our strong cultures are important to tell. Ukraine also has a very strong tradition of folk dancing and we are planning to showcase an Ukrainian folk dance group in one of the scenes at the end of the film where many different folk dance groups perform along with Estonian dancers.

Would you like one day to return to Estonia? Or is it, perhaps, easier for a filmmaker to be based in the UK?

I miss Estonia all the time. Even though I have lived away for many years, that feeling is getting stronger, not weaker. I miss the culture and my amazing friends and family. I am so lucky with the people I have in my life in both countries and the little town in England called Reepham has been very welcoming and accepting of me.

Moving full time back to Estonia will probably not happen for a while but I am hoping to share my time more across both countries. Breaking through in the UK film industry is not easy but if you do, it opens a lot of doors that I would not be able to access while being based in Estonia.

I have lived in the UK long enough, so that my rights to work and stay there did not change after the Brexit, but the country is massively affected for sure. There are huge workforce shortages in the health sector and many others.

You did some volunteering in Malawi, Africa, back in 2003 – did that experience influence your movies?

People in Malawi grow up dancing as soon as they can walk. Music and movement are in their culture and coming from Estonia, I connected to that. It influenced “The Secret Folk Dancer” – this is yet another country that keeps its traditions alive through dance and shows why it’s an important story to tell. My cowriter Stephan Drury said to me, “There is no culture in the world that hasn’t had some type of movement in their cultural expression. Language of movement is universal.”

You mentioned that as an Estonian living abroad, in the UK, you really enjoy Estonian World articles.

I love reading Estonian World and choose articles according to my mood or headlines that look fascinating at the time as my interests are wide. If there has been a topic that I have mentioned about Estonia to my friends and I see an article about it, I share it directly to them. I have also directed many of our English crew to the site.

Is there anything else you would like to share with Estonian World readers?

When I tell people in England what folk dancing means in Estonia and that I want to make a film about it, they are very fascinated and intrigued.

I tell them this example: “Imagine Morris dance teachers getting an award from King Charles for their lifetime work with teaching dancing and promoting culture. It just would not happen, or if it did, it would not be shouted about from the rooftops!”

The Estonian president does give out awards to Estonian folk dance teachers and my grandmother Elma Killing is one of them – she received one this year. She still teaches four dance groups at the age of 84 – and thanks to her, my dad teaches the dance, I danced and I taught my daughter and now I am making this film. May it long continue through generations to come.