As we celebrate International Women’s Day, it is worth taking a look at the stories of two strong and highly influential women who played leading roles in the Estonian women’s rights movement in the 19th and 20th centuries.

It took decades of political struggle to gain the right to vote for Estonian women, and this struggle has received far too little attention in the country’s historical research and even in local Estonian feminist writing.

As we celebrate International Women’s Day, it is worth taking a look at the stories of two strong and highly influential women who played leading roles in the Estonian women’s rights movement in the 19th and 20th centuries.

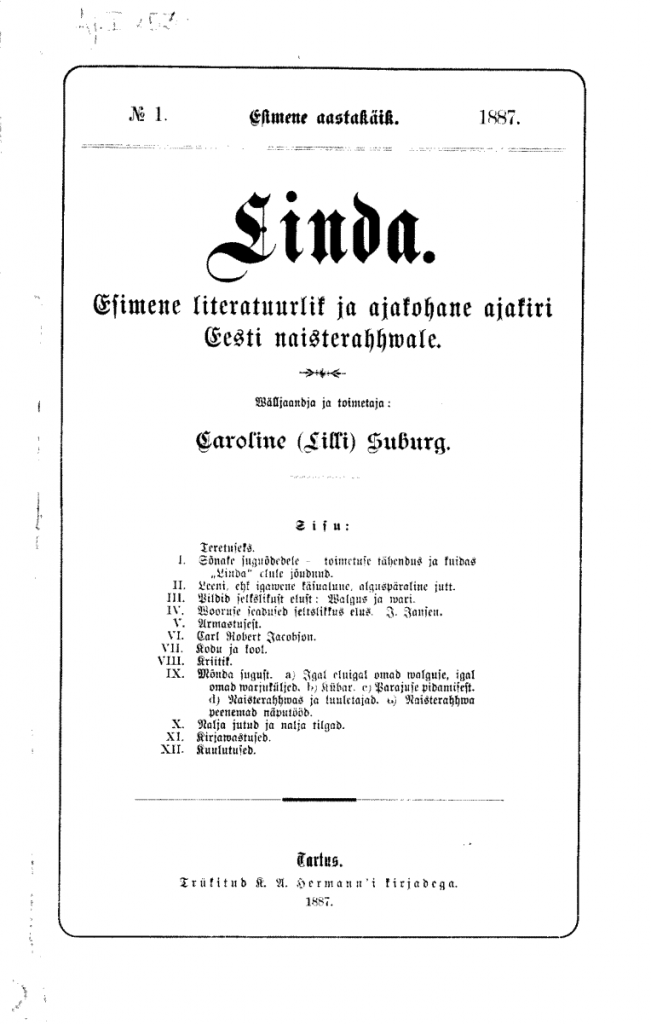

Lilli Suburg and her “Linda”

It was in October 1887 that Lilli Suburg (1841-1923), a well-known writer, educator and women’s rights activist, founded the very first Estonian women’s magazine, “Linda”.

Her newspaper and the girls’ school, which had been founded just a few years earlier, were located in the same two-storey house in Viljandi, a small town in southern Estonia. It became a centre for the cultural elite of the time; many people found their way to Suburg’s house and many of her students went on to become the first educated professional women in Estonia.

Andres Rennit, a poet who worked for Suburg during this period, writes in his memoirs: “… she was an energetic, strong-minded person with good ability and willingness to work. She never changed her mind or abandoned ideas that she had begun to think were right, and she did not let anyone influence her”.

And probably it was only thanks to this strong will and her great intelligence that she was able to push forward the national conservative public discussion and views about Estonian women’s right to study, their free choice to remain single and not to marry, to stand up and make their voices heard, and much more.

The feedback she received for her articles was not always kind. Other newspapers would publicly mock her and her writings. Women were not allowed to speak out in public, otherwise they might lose their special feminine qualities and the right to be protected by men, according to their supporters.

Her writings were, of course, radical at the time and very novel in the Estonian public media. She wrote about the importance of women’s emancipation, women’s education and international developments in the global women’s rights movement.

Unfortunately, local readers were not quite ready for Suburg and her feminist journal in Estonian. She wrote in her memoirs that some women did not even dare to read the paper outdoors, so they kept it in the barn and read it in secret, hidden from their husbands. Due to her company’s financial difficulties, Suburg was forced to sell the magazine in 1894.

Lilly Suburg died in 1923. She witnessed the political liberation of Estonian women in 1917, when women were given the right to vote and be elected. She sent her joyful greetings to the first women’s congress held in the same year and held several honorary positions in the women’s organisations founded at that time.

Marie Reisik and the “Women’s Work and Life”

Marie Reisik was born in 1887, the same year that Lilli Suburg founded her magazine Linda. Already in her childhood, Reisik met well-known and well-educated Estonian women at her home in Kilingi-Nõmme, then a small village between Viljandi and Pärnu. She attended the same girls’ school in Pärnu where Lilli Suburg and the legendary Estonian national poet Lydia Koidula had studied.

In 1907, Reisik was one of the founders of the first Estonian women’s organisation in Tartu. As women were not allowed to attend universities in the Russian Empire at that time, she went to Paris in 1908 to study to become a French teacher.

On her return to Estonia, Reisik founded the first political journal for women, “Naisterahva Töö ja Elu” (“Women’s Work and Life”). As a result of her work, many educated Estonian women united under this journalistic umbrella, and the first Estonian Women’s Congress was held in 1917. This led to the establishment of the Estonian Women’s Union in 1920.

It could be said that Reisik was a political genius because she was able to create a united front of the women’s movement that lasted almost the entire pre-war period of Estonian independence until 1940.

Despite the fact that women’s views on the wide political spectrum often meant conflict and contradicted many other opinions, the Estonian Women’s Union managed to create a large network of emancipated active women. They, in turn, had a strong influence on the development of Estonian culture and society at that time.

Reisik was elected to the Estonian Constituent Assembly in 1919 and to the parliament, the Riigikogu, in 1929 and 1932. In her parliamentary group, led by one of the political heavyweights of the time, Jaan Tõnisson, Reisik was the only elected female member. It is worth noting that in the 1929 election Reisik received more votes than Tõnisson himself.

The Estonian Women’s Union was dissolved after the Soviet Union occupied Estonia in 1940, and in 1941 Reisik was persecuted by the Soviet secret police, the NKVD. That same year she died in a Tallinn hospital in unexplained circumstances.

Today, unfortunately, Reisik’s feminist political thought is almost completely forgotten. As we celebrate the Estonian feminist movement, we should remember these remarkable women who made a big difference over 100 years ago.

* Please note that this article was originally published on 8 March 2017 and lightly edited on 8 March 2024.