Wondering for what Estonia is notable for? Searching for facts to find a reason to travel to Estonia? Looking for something to boast about with your non-Estonian partner, colleague or friend? Estonian World makes it easier for you – we have highlighted at least ten noteworthy facts about Estonia.

Estonia is a country of bogs

From any point on Estonia’s mainland, the nearest marsh is always less than 10 kilometres (six miles) away – 22% of Estonia is covered by swamps and bogs.

Stretching back to over 10,000 years, the bogs are important in Estonian folklore and seen as somewhat mysterious places. In recent years, the state has constructed many new boardwalks and watch towers; hence walking in bogs has become a popular mode of hiking all year round. And well, not just hiking – according to some locals, the bog water has some healing powers, so swimming in the bogs has become a popular activity, too.

Estonians love singing

The history of music in Estonia dates back as far as the 12th century. The older folksongs, based on poetic metre, were called runic songs. Although this tradition of singing (“regilaul” in Estonian) is still very much alive, runic songs were gradually replaced by rhythmic folksongs in the 18th century. Estonians have now one of the biggest collections of folk songs in the world, with written records of about 133,000 of them.

The Estonian Song Festival, held every five years, is one of the largest amateur choral events in the world and it’s recognised as one of masterpieces of the oral and intangible heritage of humanity by the United Nations. The joint choir usually comprises approximately 30,000 singers performing to an audience of around 100,000.

Estonia is a country of forests

About half of Estonia’s land area is covered by forests, by which the country is in the fifth position in Europe, after Finland, Sweden, Slovenia and Latvia.

The woodlands contain impressive biodiversity – one square metre of wooded meadow can be home to more than 70 different species. And the nature is appreciated – in order to preserve naturally diverse landscapes and habitats, 22% of Estonia’s territory (including the territorial sea) is under protection. The country has five national parks, 148 nature conservation areas, 152 landscape conservation areas and 538 parks and forest stands. Then there are around 100 trees – majority of them oaks, pine trees and lindens – in specific locations that are considered sacred by the people.

The density of large predators in the Estonian forests is also among the largest in Europe – but not to worry, as the brown bears, lynxes and wolves tend to avoid humans. The lucky ones, however, may get a glimpse of these animals in the forest, from time to time.

Estonians are among the least religious people on Earth

According to the results of three WIN/Gallup International polls, taken within last ten years, Estonia is the third least religious country on the planet. Just 16% of Estonian respondents said they felt religious. This number is surpassed only by China (7%) and Japan (13%).

The local census, conducted in 2011, put that number slightly higher, but still, there were about 60% of people who said they do not feel an affiliation to any religion.

Regardless, spirituality is still a player in Estonia, even in the age of machines. It’s not the approval from higher powers, but their own peace of mind that people are after – people are simply looking for answers beyond.

Estonia has produced fine composers and classical musicians

Estonian composer Arvo Pärt commands respect and admiration from classical music fans from around the world – and for the last six years, he has been the world’s most performed living composer.

But that’s not it. Estonia has produced a number of classical composers of high eminence, including Rudolf Tobias (1873–1918), Heino Eller (1887–1970), Eduard Tubin (1905–1982), Veljo Tormis (1930-2017) and Erkki-Sven Tüür.

The country has also educated a multitude of world-class conductors, such as Olari Elts, Tõnu Kaljuste, Eri Klas (1939–2016), Kristiina Poska, Anu Tali, Roman Toi (who is also a choral composer) – and last, but not least, the entire dynasty of internationally renowned conductors, Neeme, Paavo and Kristjan Järvi.

Estonians like to do things online

Estonia gave electronic signatures the same legal weight as traditional paper signatures already 17 years ago, in March 2000. In 2005, Estonia was the first country in the world to adopt online voting. By 2015, in time for the last parliament election, 30.5% of the population used internet voting. Over 98% of the bank transactions are done and 98% of prescriptions prescribed online. The e-state also means less hassle when it comes to tax declarations – 98% of those are conducted online.

And Estonians have also become habitual users on the social media – not only to share pictures of themselves and the pets, but engage also in heated discussions and arguments. Even some of the country’s ministers actively participate in public tit-for-tat on Facebook from time to time – and at least one, a former finance minister, lost his job due to public remarks on the social media platform; commenting on his Estonian-Russian colleague in the cabinet, the remarks were considered offensive.

Mind you, the online environment is actually very unrestricted – Estonia ranked first in the last Freedom on the Net index, the global internet freedom chart.

Estonia does well in basic education

According to the Programme for International Student Assessment, a premier global metric for education, compiled once in every three years by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the knowledge and skills of Estonian 15-year-olds in biology, geography, physics and chemistry are among the best in the world – the first in Europe and third on the global scale. Every time Estonia has participated in the tests, the results have improved.

The recipe for success in the Estonian basic education system consists of motivated students, hard-working and professional teachers and supporting homes.

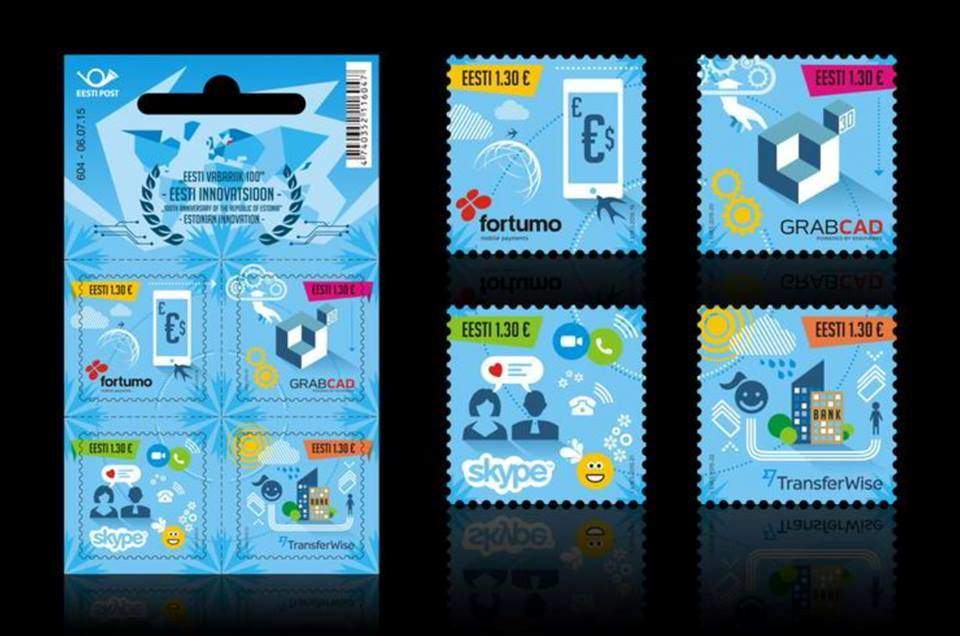

Estonia is a startup country

At some point, Estonia was estimated to have more start-ups per head than any other country in Europe. Some put it even on the second place in the world, after Israel, per capita. The latest numbers place Estonia third in Europe, with 31 startups per 100,000 inhabitants.

Some concerns persist about the sustainability of the local start-up ecosystem – many companies leave for larger countries, such as the US, UK or Germany, where funding is more obtainable – but the vibe in Tallinn and Tartu is vibrant as ever and the country will host the Startup Nations Summit in 2017. The local umbrella organisation, Startup Estonia, currently lists 413 startups – some established by founders still in high school.

People more familiar with the scene have probably become weary of hearing how Skype was invented in Estonia – its software was indeed developed by four Estonian programmers – but there are other global success stories, and more recent ones. Estonian-founded, but London-based – hence really considered a British company – money transfer firm TransferWise is now considered a unicorn (a start-up company valued at over $1 billion); a cloud-based sales software company, Pipedrive, has attracted hundreds of thousands of salesmen across the globe, and GrabCAD, a cloud-based collaboration solution that helps engineering teams manage, view and share CAD files, has now over two million users.

One of the main reasons why Estonian start-ups actively look abroad is simple – the domestic market is so small that only businesses dealing with primary needs and utilities can do considerably well. So the companies plan for market expansion – be that global or into neighbouring territories – from the outset.

Estonian is the hardest Latin alphabet-based language for a native English speaker

Estonian is the fifth hardest language to learn for a native English speaker, according to the data of US State Department’s Foreign Service Institute. Only Japanese, Chinese, Korean and Arabic are more difficult. That means the Estonian language is the first language on the list that is based on the Latin alphabet.

Estonian belongs to the Finnic branch of the Uralic languages, along with Finnish and other nearby languages. Today, it is spoken natively by just over 900,000 people in Estonia and about 160,000 outside the country.

Estonia is a country of manor houses

As part of the Baltic German heritage in Estonia, the manor houses were once seen as the relics of oppression and neglected for decades. However, the tides of history have a habit of sometimes making sudden turns and so these days, the manor house complexes are under state protection and there is virtually nobody who would not consider manor house architecture as part of Estonia’s national treasure.

The skills that ultimately led to building stone castles and manor houses in Estonia were brought along at the beginning of the thirteenth century by German crusaders who invaded what was then a pagan country. Starting with stone-built churches in the process of imposing Christianity on local natives, the new ruling class soon also needed personal strongholds in order to manage the conquered areas and conduct economic activities. That’s how the impressive manor house architecture came about.

The vast majority of the imposing manors were built over a century and half from 1760 until the beginning of World War I, mostly in the baroque and classicist styles. By that time, there were around two thousand different manor centres, if one includes separate building complexes of main manors and pastorates.

The old Baltic German nobility became completely obsolete after Estonians fought and won their independence in 1918. The manors were confiscated without compensation and the lands given to Estonian peasants instead – although the country relented some years later and agreed to reimburse 10-20% of the value to their former owners.

Apart from the manor complexes that were turned into schools, orphanages or sanatoriums, large number of the historical buildings became dilapidated over the next 60 or 70 odd years. The Soviet rule that considered the large landowners “enemies of the people” by default, didn’t help along in restoring the manors’ former glory. Despite of the Soviet hostility, some buildings were renovated; most notably Palmse manor (renovated 1973-1986).

In the last 26 years, however, since Estonia regained independence, both the private and institutional money has performed miracles and hundreds of buildings have been expensively restored, either housing hotels, conference centres, spas or, indeed, private homes. According to the Estonian Manor Portal, there are currently 414 manor houses that have more or less retained their original form and are in very good or good condition. But there are still many left that have not been restored and still hoping to find a proud owner – fancy buying a manor house in Estonia?

I

The cover image is illustrative (photo by Hando Nilov/courtesy of EAS.) Please consider making a donation for the continuous improvement of our publication.

Super presentation! Congratulations.