Tatiana Akopova, a social media marketing specialist, who moved to Estonia from Russia, has been reading Estonian folk tales and now shares what she thinks they could tell us about contemporary Estonia.

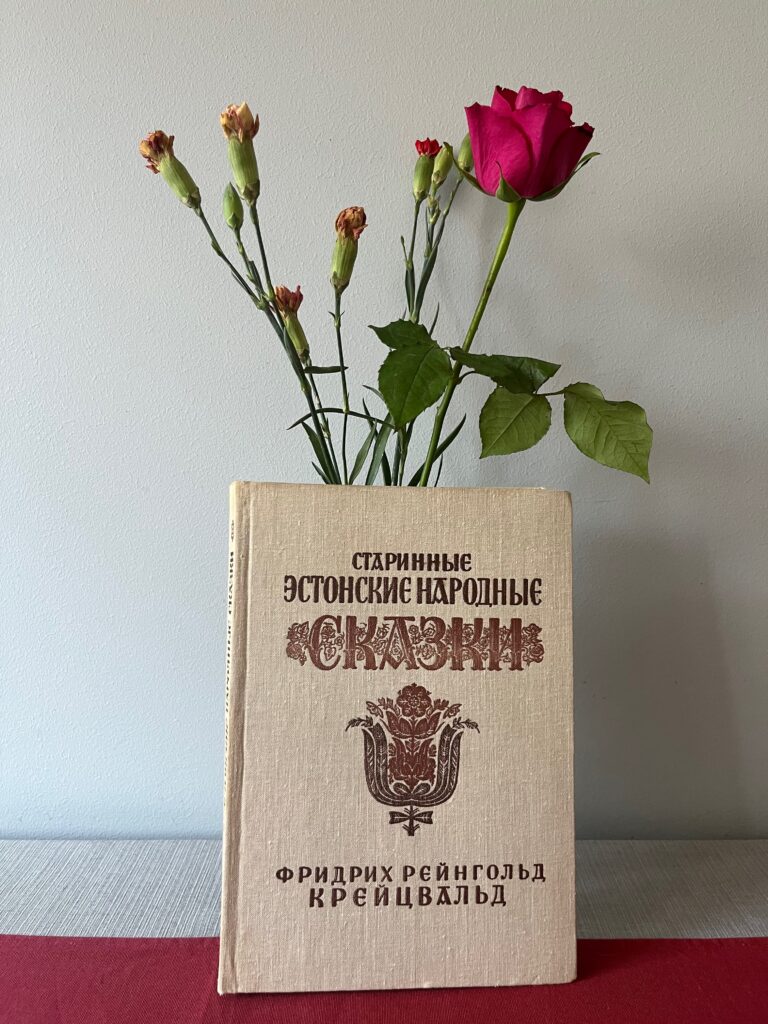

Ah, the rich tapestry of Estonian folklore: where cunning peasants, Finnish sages and conniving crayfish share the stage in teaching us about life’s complexities. I’ve been on a humour-infused journey with 30 Estonian folk tales as published in Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald’s “Old Estonian Fairy-Tales” (1866) – and I am now ready to share what they could tell us about contemporary Estonia.

The patriarchy parade

In Estonian folk tales, men are pitied if they don’t have a wife “to darn their socks” and unmarried women are looked down upon and pitied if they have no children. “My husband has long been fed up with me, he looks at me like a dried-up stump that will never produce young shoots, the neighbours are much happier than me, they all have a house full of children. My house is empty, and I am like a dry stump without branches or shoots,” a childless woman in one of the tales says.

The notion that a woman’s worth is solely pegged to her fertility or marital status is outdated in a country like Estonia, which has managed to build a digital society with equal opportunities for education and employment. However, it would be naive to claim that Estonia or any other country has completely eradicated patriarchal thinking.

Sure, you might not hear modern Estonian men referring to their wives as “dry stumps,” but issues like gender pay gaps and underrepresentation in certain professions still exist. And like anywhere else, domestic violence remains a concerning issue, although, thankfully, the society has moved past seeing it as acceptable for a man to “shut his wife up with his fist” like in tales.

Sage or sorcerer?

Ah, the ubiquitous Finnish Sage (Väinämöinen in Finnish; a demigod, hero and the central character in Finnish folklore and the main character in the national epic Kalevala. In the Estonian national epic Kalevipoeg, a similar hero is called Vanemuine) – a guru for the Estonian wanderer lost in the forest or adventuring abroad. Like the forest-dwelling equivalent of a life coach, but with better facial hair and a penchant for mystical giveaways. It’s as if Estonian folk tales were saying, “When in doubt or danger, find your nearest Finnish elder!”

Now, the recurring motif of a Finnish sage in Estonian tales might be more than mere folklore magic; it could well reflect the historic and cultural bonds that tie these two nations together. Estonia and Finland share linguistic roots, and their histories are full of mutual influence and exchange.

Alternatively, in today’s global economy, this could be seen as a nod to international collaboration and the benefits of seeking wisdom beyond one’s borders. The Finnish sage in the tales can be seen as a metaphor for being open to wisdom, technology, or approaches that come from other places, even if it’s as close as across the Gulf of Finland.

The matchmaking game

Turns out finding love in ancient Estonia was like surviving gladiatorial combat. In ancient Estonian courtship, finding love wasn’t just about winning hearts – it was a full-blown battle royale!

Imagine ancient Estonian bachelors not handing out roses, but instead, say, engaging in aggressive log-tossing, bear-wrestling or extreme bog-jumping just to impress a potential spouse. Yes, turns out the path to matrimonial bliss was paved with sweat, blood and quite possibly some broken limbs.

Back in the day, these physical contests were perhaps seen to prove one’s worth not just as a husband, but also as a protector and provider. Today, however, attributes like emotional intelligence, career stability and shared values have joined the fray as desirable qualities.

Perhaps this reflects Estonia’s evolution from a society where physical strength was a key survival trait to one where intellectual prowess is equally valued. The ancient tales and their strongman competitions for wives may now seem outdated, but they offer a fascinating glimpse into the priorities and anxieties of a bygone era.

The modern Estonian dating scene involves fewer tests of brute strength and more civilised activities. Think of online dating profiles filled with sunset photos and favourite hiking spots, rather than a list of defeated foes. Swipe right, and you may find love; swipe left, and the only thing you’ve defeated is a bad match, not a literal bear. And it’s become easier to “swipe left” on strange wizards offering buns.

The bagpipe of doom

Some fairy tales (for example “Thunder Bagpipe”) warn against making deals with the devil. A popular character, a merchant, agrees with the devil that he will serve as his servant for seven years and do all his bidding. As a reward for his service, the merchant promises the devil his soul.

Couldn’t it resemble modern Estonia with its soul-crushing deals related to mortgages? In yesteryears, the devil was more straightforward about wanting your soul. Now, he masquerades behind terms like “fixed interest”, “amortisation” and “early repayment fees”.

In modern Estonia, the devil might not show up in person, but, boy, does he have a seat at the table when mortgage agreements are being signed! Your soul doesn’t belong to Satan; it belongs to the bank for the next 30 years.

In folklore, the devil loves contracts that are filled with nasty surprises. In a similar vein, modern mortgage contracts are notorious for clauses and terms that could make even a law professor’s head spin. No one has ever found joy in reading through 30 pages of legalese, but failure to do so might just lead you down a rabbit hole of fees, adjustable rates and other fiscal nightmares.

Both the tale and the modern scenario hint at the dangers of instant gratification and shortsightedness. The merchant wanted quick gains without considering the eternal cost; similarly, people often jump at the chance to own a home without fully considering the long-term financial commitment and potential pitfalls. It’s as if the folk tale is an ancient Estonian’s way of saying, “Think before you act, especially when contracts and your soul are involved.”

The magic crayfish

Ah, the talking crayfish and its magical brethren! These magical creatures are like the Amazon Prime of fairy tales; they deliver your wishes almost instantaneously. The presence of these magical beings serves a dual role.

First, they act as the facilitators of desires, the ones who make dreams reality. Want to be a prince? Snap, you’re a prince. Wish to have endless riches? Poof, here’s a pot of gold. These creatures embody the fulfilment of human desires in their most immediate form.

The second function is the cautionary tale aspect. Just like the talking crayfish, who at first seems like a bottomless vending machine of dreams, they often introduce a catch or a consequence. Essentially, they’re like magical therapists; they make you confront the emotional and ethical repercussions of your deepest desires. “You wanted unlimited wealth, but did you also wish for eternal greed?” they seem to ask. They teach that every choice comes with consequences, and one should weigh their wishes carefully.

In modern Estonia, a nation characterised by its rapid digital transformation and its reputation as a “start-up country”, the fairy tales serve as a cautionary tale. The magical creatures remind us of the downside of instant gratification and the risks of not thinking things through – a message incredibly relevant in an age where we can order food, summon a car or even find a date with a swipe on a screen. In a world that often caters to our every wish, these stories remind us to pause and ponder the ramifications of what we desire.

Not wish-granters but wisdom-granters

So, the magical creatures in Estonian fairy tales serve not just as wish-granters but as wisdom-granters. They give us the best of both worlds: the joy of seeing dreams fulfilled and the valuable life lessons that come from understanding the price of those dreams.

And in a world where technology can make so many of our wishes come true almost instantaneously, those lessons are more important than ever. They teach us that even in a world of endless possibilities, it’s still crucial to choose wisely. Because whether you’re dealing with a talking crayfish or a talking Siri, the rules of wish-making haven’t changed all that much.

Although centuries apart and existing in very different realms – the mythical and the modern – these characters and stories from Estonian folk tales continue to resonate.

They’re timeless not just as stories but as allegories that reflect human behaviour across eras.