Estonian photographer Tõnu Runnel has published “Eesti”, a book of Estonian photo stories, published in both Estonian and English; Estonian World publishes a few pictures and excerpts from the book – an album of everyday life in Estonia.

Here are a few excerpts from “Eesti,” my book of photo stories from my homeland. The book has 100 photos and 90 stories, 80 of which I wrote myself and 10 were contributed by some great co-authors. The English translation was done by Villu Arak.

Double decker. A Sunday stroll is perfect for admiring wooden houses in old districts. Elegantly weathered facades, large trees and two-story sheds. The city puts these sheds under heritage protection while developers replace them with shed-like homes.

Living in an unrenovated and poorly insulated wooden house is notably less romantic. Feeding a wood-burning stove can mean hauling firewood from the second floor of the shed (where it had to be stacked previously).

Residents who can afford it install central heating and insulate their houses. They’d rather limit cultural heritage to other people’s yards, preferring to see something other than those damn sheds from their window.

As I was taking this picture, a man stepped out of the neighbouring house. “What a beautiful view you have here!” I said. The golden maple and all. “It’s almost November,” he quipped.

Abandoned. A vehicle’s last ride doesn’t always lead to the scrapyard. It can be a nice family trip to the country house. But the car conks out – a short circuit or something. Let’s push it over there for now until we figure out the busted bits. In the meantime, we’ll get another daily driver.

Such wrecks are sometimes never taken to the scrapyard and deregistered. Southern Estonia has plenty of magnetic homesteads that have attracted an entire fleet of old beaters. You never know when you need one, amirite? Got it for free anyway. Many carcasses also seem to end up on the Estonian islands. A one-way ticket to a lovely sea view.

A precious few of these sleeping beauties are revived before the elements complete their patient demolition job. Even so, the visual value of a forgotten vehicle actually improves. It’s a museum piece that gradually becomes a vintage rarity – a landscape sculpture. Until it finally becomes one with the potato patch.

Meal. Manmade landscapes of horror can be poisonous when they pollute groundwater and spew toxic dust, but they’re grimly picturesque. Which makes me wonder whether we should preserve them while neutralising the hazards. The ravaged landscapes of Ida-Virumaa are already being preserved and put to good use instead of being hidden and levelled. Yet all the effort and trouble that went into constructing Tartu’s gloomiest picnic spot or museum of landscape art was written off. No more black tire mountains. It’s just an ordinary wasteland now.

Sometimes it seems our pursuit of tidiness makes us too dull. But then I remember clean air and groundwater. OK, fine.

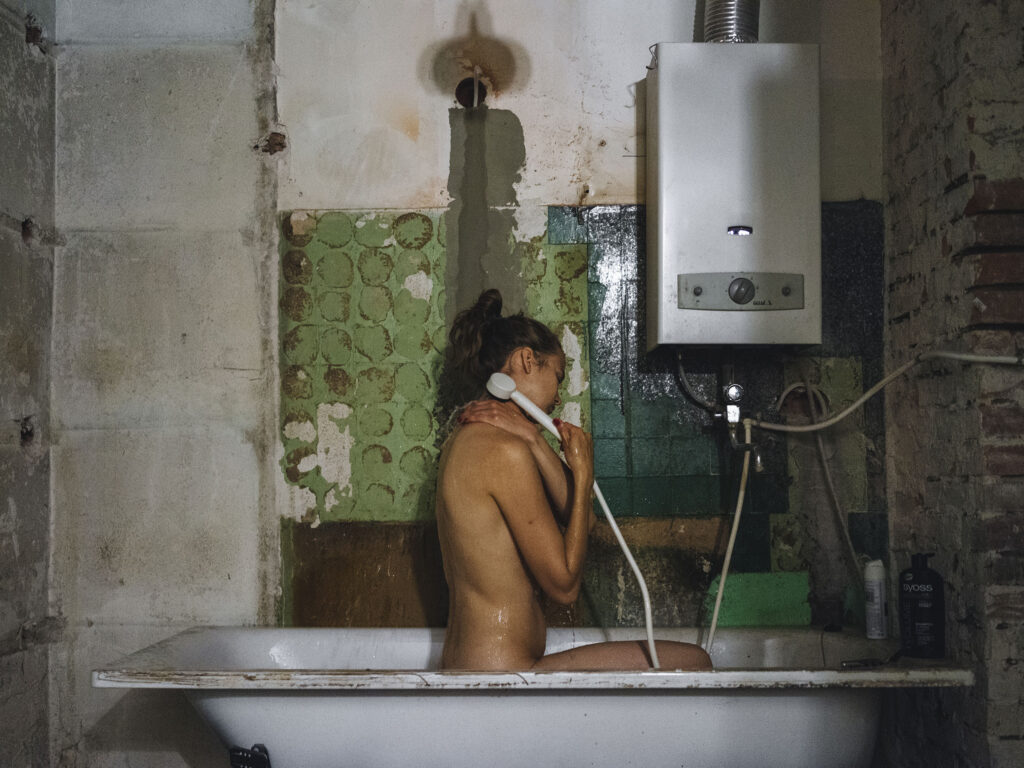

A sense of home. You can buy a house. A home is born from living in it. Cook in the kitchen, sit at the table and have a meal. Sleep. Lie down in the living room and read a book. Get friends to come over. That’s how your property becomes your home.

A home has to be built. You can start from scratch: felling the trees, peeling and chopping the logs… dear god, let’s move on. Take over someone else’s home and change it to your liking. At least change the wallpaper. No need? Well, go through every square inch of the place, move the furniture around, change the bed linens, hang your pictures on the wall, and put your food in the fridge. Do something. A home is born from living in it.

You don’t even need to make repairs. So what if it looks like a run-down shanty? As long as you clean it up (and yourself, too), it’ll be home.

General plan. Now and then, authorities set out to reinterpret Estonia’s capital, shaping ambitious ideas into a master plan. They explore where and how densely the city should grow, how its parts are linked, how to rectify previous efforts, and how the overall city experience should feel.

By modernism’s heyday, old working-class neighbourhoods had wilted. Their evolution had been quite haphazard anyway, so there was an urge to replace them with comfy, pretty and orderly new micro-districts. These housing projects would have all the mod cons, wide thoroughfares and clean, grand spaces. Such vast changes not only risk failing to properly appreciate the recent past – they’re also too enamoured with the current thing, idealistically overestimating trends and thought patterns that will inevitably change.

Overblown plans tend to hit a concrete wall. There is never enough money, power or public support to tear down and replace entire districts. Unfulfilled futures then leave us with modest mementos: one house, one block and one four-lane bridge that peters out at three wooden houses refusing to die.

A rich city is one that’s been poor enough to avoid complete transformations. Instead of destroying all traces of previous eras, it has tacked on a layer from each one that comes along. A slice of postmodernism between wooden-lace fretwork is simply exquisite.

Hood. Somehow, repairs get done, windows installed, walls put up and electrics cabled in. Even a minuscule effort can squeeze a flower garden between the pavement and the foundation. Who knows if it’s the asphalt or the foundation that keeps the other one from cracking, but that’s how they preserve the quaint charm in Tartu’s Supilinn (literally, Souptown). Contrary to popular belief, even the rough plastic windows – installed on the wrong line, in the wrong size and with pointless panelling – are part of the milieu.

I’m glad that cool houses are being tactfully, thoughtfully and meticulously restored. But if it’s interspersed with some rickety, survivalist construction, even better. Adds to the charm. Without a plan or the ability to do it right. Spray foam poking out through the metaphysical interstice between the plastic and the ceramcite blocks – that’s the special yellow sauce of a proper milieu.

Delightful decay, lace curtains and window trims from the “Let’s just nail some random boards here; I’ve got some in the shed” department also add to the experience. Those moss furrows in the roof garden and that thingamajig on the roof that they haven’t bothered to remove for 12 (or was it 24?) years. What’s the rush now. It takes how long it takes.

In the background, boring new architecture is creeping in. In these parts, money will likely not be found for the wonderful new. This, too, is a kind of milieu. One day, it will use a knight’s move to conquer this old house miracle. The ceramcite firewall on the left probably suspects that before that happens, things might get very hot for a moment.

Forest people. Cities are nice, but in the end, the Estonian heart is drawn to the countryside, the forest and the bog. In summer and winter. Alone and with family, sometimes with friends. Hiking food in the backpack, berries and mushrooms waiting in the forest ahead. To listen to the silence, to watch the clouds drift…

Oh, shut your trap. The Estonian hauls tires and construction waste into the forest (there’s always a toilet bowl!), drives his SUV to the steps of the (free and state-maintained) hiking house only to run the car stereo at full blast, dumps trash at the campfire site, throws a shedful of firewood into the well, burns the furniture in the hiking house (there’s no firewood, right?) and, upon leaving, knocks down the information stand. When he gets home, he turns his own forest into money and buys a huge-ass TV.

Raise your kids as people of the forest. Hot or cold, take them hiking and immerse them in nature. Criss-cross Estonia together. Instil this land and forest into their hearts. Cities and villages, too. One day, we may even become a forest people.

Tõnu Runnel’s new book is available in Estonian book stores and can be ordered internationally from Krisostomus.

Please see also Tõnu Runnel’s photoseries Eesti blues, Eesti noir, Eesti home, Eesti mist and Eesti autumn.